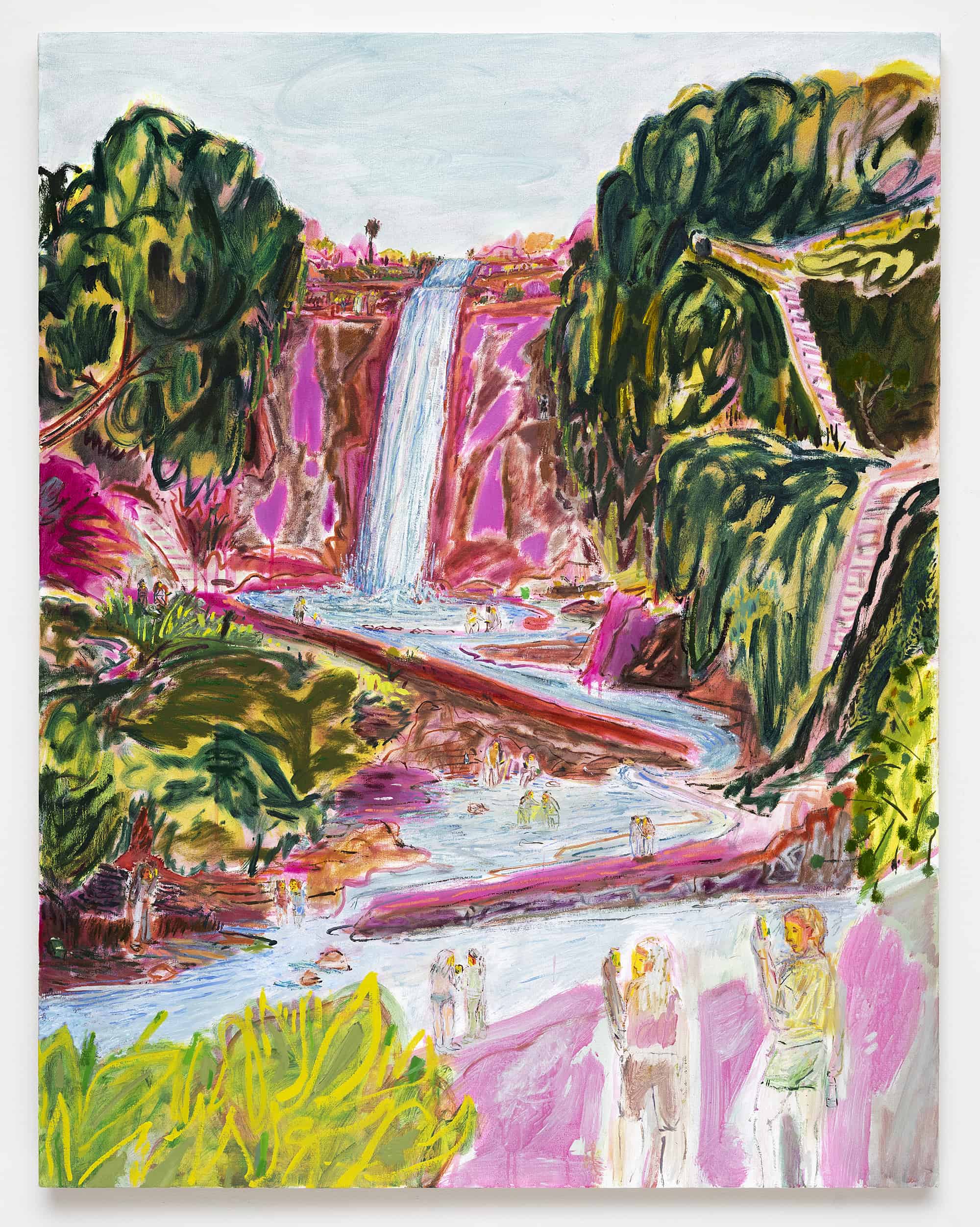

Lisa Sanditz, Kaaterskill Falls (2022)

House Representative for Georgia’s 14th District, Marjorie Taylor Greene tweeted recently that she wants a divorce. Not a marital divorce but a national one – she cites irreconcilable differences. Quite how a nation divorces itself remains unclear, but Greene proposes red states and blue states go their separate ways because the gulf of ideological difference has grown too great to repair. This declaration from the Republican representative comes a couple of weeks after President Joe Biden delivered his State of the Union address to the United States Congress. An annual tradition of American politics, the speech relays to the government and the people the current condition of the nation.

Evergreen is Sanditz’ own State of the Union; weaving personal narratives and global events together, the artist inextricably binds the two in a suite of eleven new paintings that chronicle contemporary American experience. Her canvases balance despair, and a quietly controlled rage, with a gentle humour and just a glimmer of hopefulness that probe the contemporary moment.

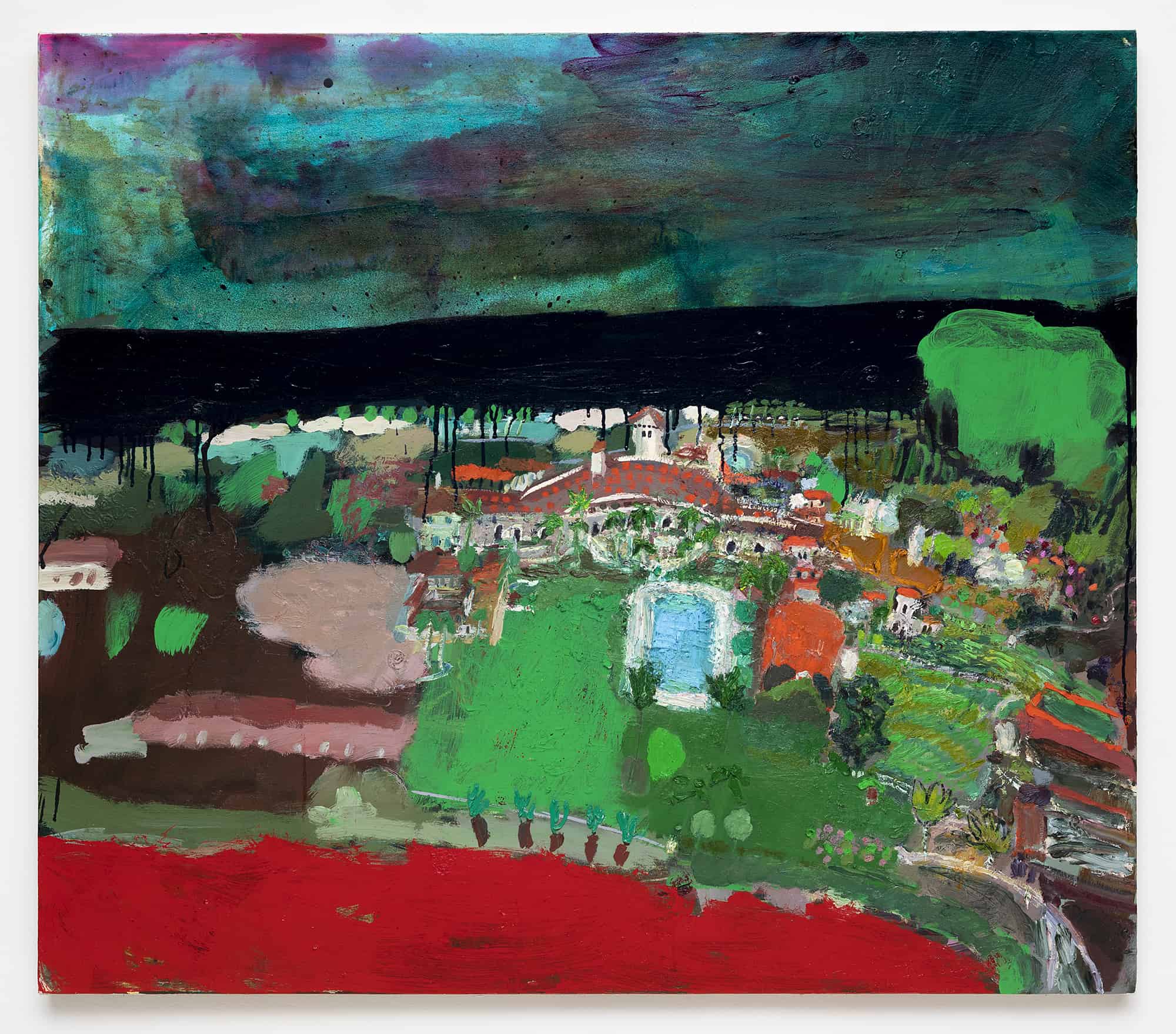

Sanditz’ early works focused on the relationship between the landscape, commercialisation and environmentalism. Her vibrant canvases pictured waterways glistening with microplastics, natural landscapes glowing luridly with artificial chemicals, tracts of land that had been over-developed and transformed into factories and other sites of production. These themes continue to play a significant role in Sanditz’ work, exploring them through an allegorical framework. Mara-Fucking-Lago, for example, seeps thick black paint, resembling an oil spill, across its horizon line, conflating a natural disaster with Trump’s estate and by extension its resident.

Lisa Sanditz, Mara Fucking Lago, (2022)

In recent years, Sanditz’ scope has both contracted and expanded, confounding both global events and those closer to home. Her paintings are personal responses to her subject matter, which explore her own relation to and complicity in events, as well as acting as arenas for broader investigations of contemporary culture and politics. In the same way that Edward Hopper’s realist paintings suggest the isolation and untethered nature of modern living, and Norman Rockwell’s conjure something of the simultaneous fear and opportunity of the 1950s and Cold War era, Sanditz’ work records a contemporary malaise.

For Sanditz, this feeling has deep roots. The Hudson River School of artists, founded by Thomas Cole in around 1825, was organised around the three principles of discovery, settlement and exploration. The group presented the American landscape as a pastoral setting, where humans and nature coexisted peacefully. One of its most celebrated proponents, reviled for most notoriety by his own student, Frederick Church, Cole, created allegorical paintings that sought to represent America as an idyll free from urbanism and the industrialisation that had swept his native England. Imbued in his work was a religious morality which saw America as a land of exception, a view that was shared by religious settlers of the country, and one which still holds strong in the national imagination.

Cole’s painting of the Kaaterskill Falls in the Hudson Valley embodies the movement’s core tenets. He depicted the falls as an Edenic paradise, with plunging falls surrounded by luscious, undisturbed greenery and a heavenly sunlight breaking through the clouds. Presenting the American landscape as a divined land was central to the belief of North American settlers, who believed that the land had been ordained by God for them, and on whose authority they should continue to expand their settlements built on the ancestral lands of the Mohawk and other Haudenosaunee peoples: the Mohican, Lenape, Munsee and other Algonquian-speaking populations. ‘Manifest destiny’, as this came to be known, was the foundation on which Westward expansion was built, that and later the discovery of large gold deposits, and a principle which categorically entwined the landscape to the colonisers.

Any divinity has left Sanditz’ painting of the same falls Cole painted. Still overgrown with green, Sanditz uses bright pinks to bring form to the painting and contrast with the cool blue of the water, gently nodding to the hyper-masculinity of the Hudson school. Groups of bathers dot the river’s edge and in the foreground two hikers stand taking in the scene through their phone screens. The artist states: ‘In my painting, the humans fade into their solipsistic worlds, while the landscape itself pulsates with colour.’

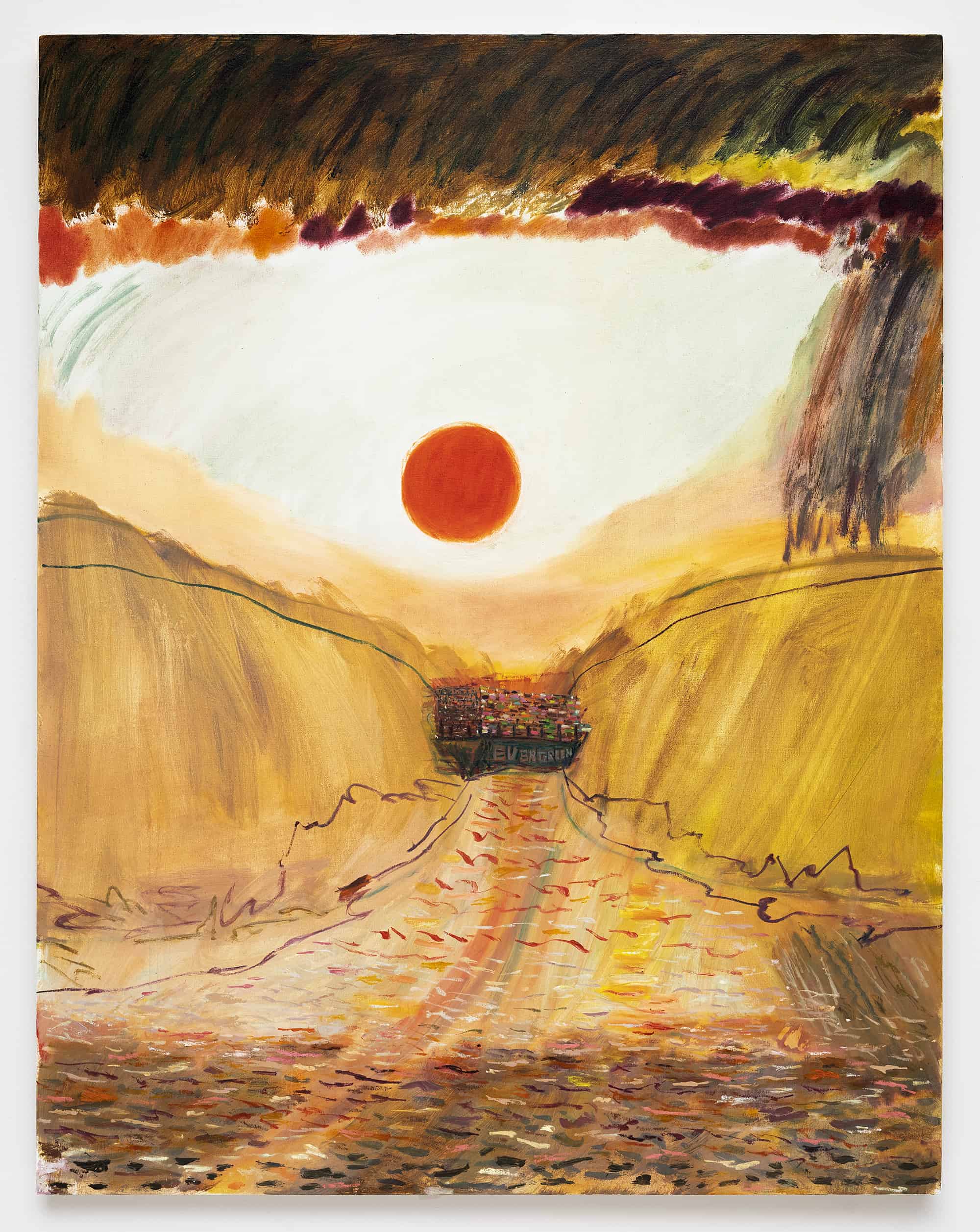

Lisa Sanditz, Evergreen, (2022)

Sanditz’ paintings reveal the flawed logic of American exceptionalism and the selectivism of the Hudson River School’s romantic ideals. In Sugar Bear (Bear Eating Skittles) the creature’s organic diet is replaced with E numbers digested from a packet of skittles. The acrid, candy colours of the sweets replicate themselves in the landscape of the painting, dashes of purple, orange and pinks glinting across the canvas. The skittles are emblematic of broader infiltrations of the modern and man-made into our natural surroundings. For Sanditz, who states, ‘things move quickly in the American landscape’, industrialisation and development are baked into the earth of the country.

In dismantling these pedestalled American myths, Sanditz records an alternate condition: one in which we are caught in a disorientating feedback loop that ricochets between the absurd and the banal, conviction and stasis. For example, a full grown tiger on the loose in the suburbs of Houston causes no bother, it merely becomes clickbait for social media and the 24 hour news cycle. It is the unselfconsciously chirpy message on a birthday balloon telling us to stay fabulous, walkers carrying on as their world is flipped upside down, the restlessness that leads to early morning fridge raids. Sanditz not only documents our paralysis, but asks what it is going to take for us to break this cycle? Interestingly, the Mohican name for the Hudson river was Mahicannittuk, meaning ‘river that flows both ways’, the hudson river is tidal up to 100 miles north of New York harbour, suggesting an earlier understanding of the dualities of the landscape and world that Sanditz later identifies.

The painting Evergreen brings this exploration full circle. Sanditz pins us between the steep, sandy banks of the Suez Canal, ahead there is a blockage: a very large container ship has wedged itself between the sides, unable to move. The incident which Sanditz depicted actually happened, and caused consternation, endless memes, and a standstill in one of the world’s busiest shipping channels. For Sanditz there was irony in the shipping company’s name, evoking natural phenomena and perpetuating cycles. Causing a break in global supply lines, the crisis brought an otherwise overlooked or invisible process to the forefront and presented the opportunity for more expansive exploration of consumerism and wider culture.

It is interesting that volcanoes are a recurring motif in Sanditz work; she has returned several times to Mount Vesuvius, whose eruption and magnitude of impact wiped out two established cities of Ancient Rome. That quietly controlled rage is beginning to make its presence known, and Sanditz paintings are a reminder of the devastation that bides its time, waiting to explode. In the meantime, at least she is here to document it all

(By Alexandra MacKay)