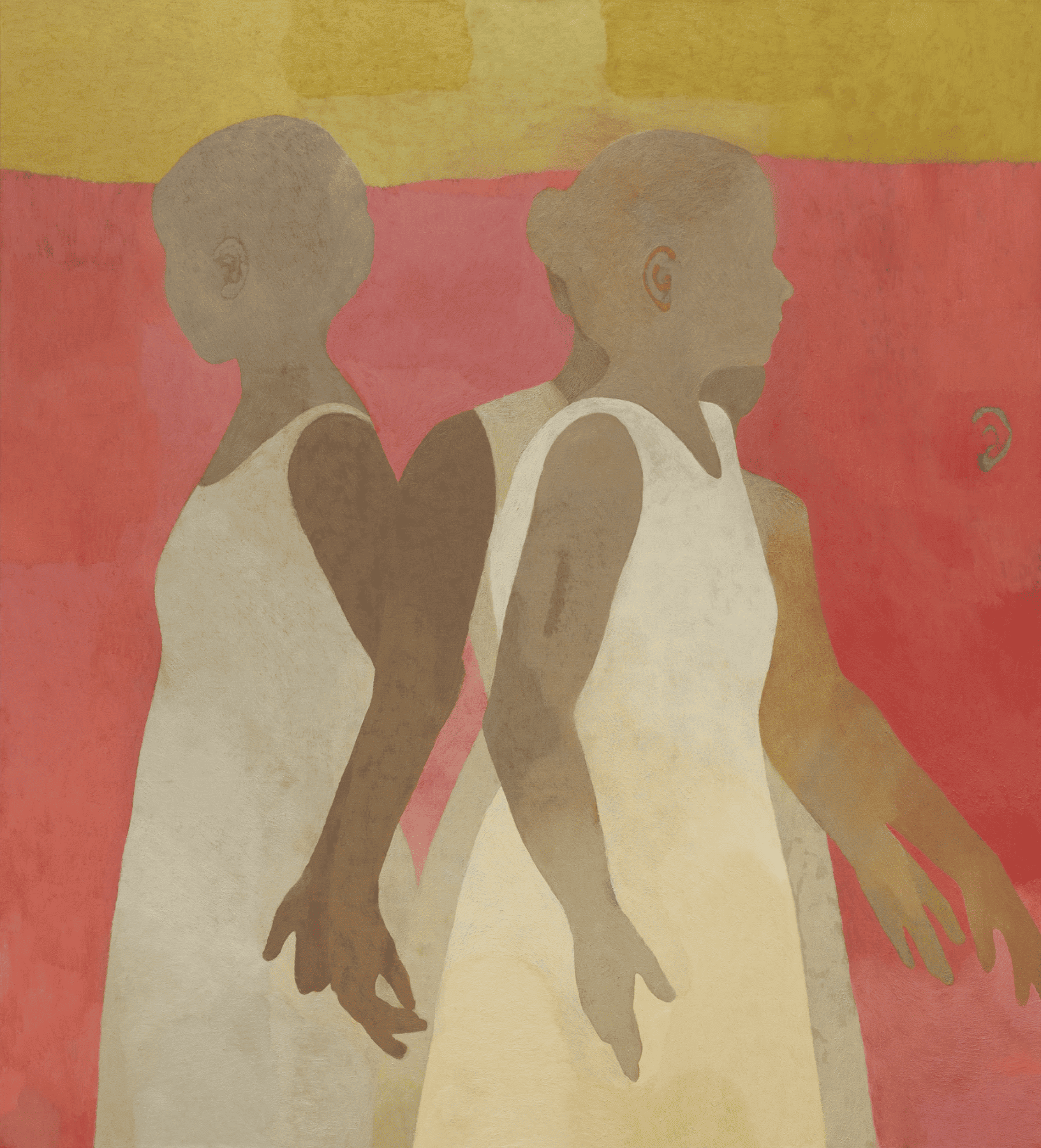

matriarch, 2023

This text was commissioned on the occasion of Catherine Repko’s 2023-2024 solo exhibition, a new season’s dawning, and produced in an accompanying artist’s book. The text is written by Eloise Hendy, writer, critic and poet.

Three hands touch, fingers interlaced in a soft knot. A woman lies on her side, surrounded by a wash of white like snow, or faded memory. A hand on the shoulder; the small of the back. A group of girls stand so close their arms merge – becoming one body, one many-headed creature. Another group of women stand on a threshold, at the edge of water perhaps, their backs turned. What are they looking at, these girls, these sisters?

In Catherine Repko’s work, a sister is a shadow, an echo, a myth, a dance, and a ripple in a pool. The third of four sisters, Repko grew up in a close-knit, all-female world. It was also a world that didn’t stay still. “We’re American,” Repko tells me on a blustery afternoon in her London studio, “but we lived in Germany, Italy, and Ireland in our childhood.” In each place, friendships had to be built from scratch, making the ties between sisters tighter. And yet, while Repko’s paintings certainly depict a kind of closeness that verges on immersion–girls “joined at the hip”, faces and limbs over-lapping like waves–at the same time, they seem to hum with distance. In one new painting, three girls face each other, one bending down as if about to speak some secret phrase, but another figure hovers mostly out of frame. Often Repko’s figures are sliced at the shoulder or neck, the canvas unable to contain them. They are already almost elsewhere; you see them but cannot catch them. The spaces between her figures too, often seem like figures themselves; like presences. Here then, the bonds of sisterhood might be unbreakable, but they also must stretch, shift and sprawl. Within their very closeness, they live alongside their separation.

This year, Repko got married. She was the last of her sisters to do so. And in her paintings, the recurring girls seem to hover at the far-edge of adolescence (that volatile time, when adulthood seems sublime: awe-inspiring and terrifying). Repko is interested in the very notion of transition–the point at which her sisters’ focus shifted, onto new nuclear families, and, more broadly, the moments when close-knit, childish ties alter and loosen. Marriage, after all, is traditionally conceived as the crossing of a threshold–from girlhood to womanhood. Traditionally, it is also thought of as both a time of radiant joy, and loss. The bride is ‘given away,’ like a trinket. And so, Repko’s paintings ask, what does it mean when sisters become wives become mothers, while remaining sisters still?

In 1995, Repko’s family moved to a town near Florence. Going to school in the city, the young sisters were surrounded by Renaissance frescoes–Virgin Mothers, saints and angels forming strange lineages, all dressed in the same draping folds. Decades later, in Repko’s studio, this“world almost-lost” to her returns. Drawing out figures from an archive of family photos, and animating her girls in new arrangements, in Repko’s early paintings she performed an uncanny conjuring of sorts. Each painting became akin to a faulty memory–a trace of something that almost-happened. Soon, Repko found a way to evoke memory and the passage of time in her works’ very texture. Unable to use her studio during lockdown, she made a series of oil pastel drawings. The creamy pastel had a tactility she had been reaching for–one that reminded her of the frescoes she’d once been surrounded by. Seeking to recreate this quality, she mixed paint with marble dust, which develops a “velvety, paste-like texture, a stone-like quality when dry”. That strange and distant realm of otherworldly figures caught in rock–the “world almost-lost”–re-emerged. The sisters were turned to saints and stones.

the founding, 2023

One of Repko’s paintings from 2020 is titled an acute nostalgia. In it a woman appears enveloped by white, like a fading memory latching onto the emotional weight at its core. More than anything, it is this ‘acute nostalgia’ that animates Repko’s work. In reference to her early sister paintings, Repko recalls a phrase from Rebecca Schneider’s Theatre & History: “A repeated gesture, an aged object, cliched phrase, an old letter, a footprint, a way of walking–all of these things, material and immaterial might drag something of the no longer now, the no longer live, into the present, or drag the present into the no longer now”. With the sisters as repeated gestures, and her stony paintings taking on the appearance of aged objects, Repko drags the no longer now into the present, and the present into the no longer now. “You’re moulding, and then it hardens and it’s always going to be there,” Repko says. “All these memories, you’re solidifying them, and that act is what I’m addicted to.”

Really, the “almost-lost” world Repko’s work orbits is the state of girlhood itself–slippery and transcendent; darkly beguiling because its destiny is to be lost. In her first painting in this new series, sacred, for instance, two girls seem to follow a third figure out of frame. The marble dust has made their stony bodies patchy, as if already aged, but between their faces is a flash of blue. Renaissance frescoes are known for their dazzling Ultramarine. But, after the best quality Ultramarine pigments were removed from Lapis Lazuli stones, the leftovers were also used. This created Ultramarine Ashes, a weak grey-blue colour (a memory of colour? A colour almost-lost?) This is the hue that peeps through this first new painting, which hung in Repko’s studio like a talisman, while she dragged the others into the present.

Looking at it–at the figure already over the other side of the frame–I think of two well-known words that can’t be translated into English; notions that dance around nostalgia, like sisters. The famous Portuguese ‘saudade’: “a deep emotional state of longing for an absent something or someone that one loves,” and the Welsh word, ‘hiraeth’: “a homesickness for a home to which you cannot return, a home which maybe never was.” Both are truly bittersweet–love shot through with the melancholy of longing.

To me, Repko’s paintings sound like Max Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight–soft, slow chords pierced by soaring strings; hovering somewhere between grief and exaltation, somehow comforting and heartbreaking at the same time. Daylight too, of course, is fleeting, and in Richter’s strings as in Repko’s paintings there is a sense of looking back at radiance from the “almost-lost” of dusk–an attempt, the composer has said, to create “luminous music out of the darkest materials”. To sculpt dancing girls from dust.

“The sisters who were a physical support system, started becoming a psychological support system,” Repko tells me. They developed into characters, archetypes even. Symbols of something intangible but persistent; untranslatable but ever-present. For instance, Repko shows me a fresco by Pierodella Francesca, The Queen of Sheba Adoring the Holy Wood. The Queen kneels with her hands raised in prayer. A group of women stand at her back, one with arm outstretched, as if gently touching the Queen’s shoulder. “It’s not a wedding, but it could be,” Repko notes. “It’s a scene where a woman is with her team of women, supporting her and bringing her there.” Forged from memories married with such redolent scenes, Repko’s works properly belong in the realm of myth. What is a veil, a dress, a body, a shadow? Who is a sister, and who is a mirage? One symbol provides a final clue: on frame after frame, ears like seashells seem to catch the sister’s secret whispers. Listen, they urge. But of course, what you can really hear is a distant and secret realm of yourself, echoing back to you like waves

(By Eloise Hendy)