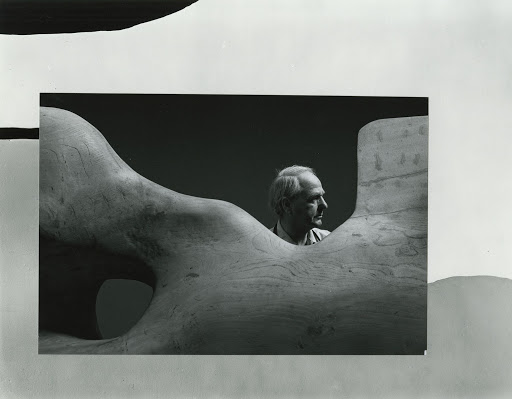

Arnold Newman’s 1966 portrait of Henry Moore was taken at the artist’s home, Perry Green, Much Hadham, where the artist had moved after his house in the artist enclave of Hampstead was hit by shrapnel in September 1940. In the photograph, the artist’s profile can be seen behind the curves of the sculptor’s archetypal reclining figure. The full extent of the sculptural form is cropped by Newman, rendering the sleek wooden curves of the nude an amorphous abstraction. By contrast, Moore’s profile is sharply defined by the fall of light across the artist’s face.

The form of the sculpture here is the opposite of that which Newman finds in his most famous portrait, of Igor Stravinsky – in his own words, a form which is ‘strong, linear, harsh, but also lyrical and beautiful.’ Nonetheless the sculpture’s curves are equally symbolic: the artist dwarfed by the magnitude of his creation. In this, the portrait is typical of Newman’s environmental portraiture, but this was a term which the photographer himself found difficult to align with. Also finding the term deprecatory in the context of Newman’s portraiture, the noted art historian William A. Ewing has suggested Newman ‘found it devalued his symbolic and psychological aspects, which he considered just as, if not more, important.’

At the time of Newman taking his portrait, Moore was considering his legacy. By the later twentieth century Moore, along with Barbara Hepworth, had secured a prominent position in the history of British sculpture, by way of the export of sculptural tropes abroad alongside domestic commissions. Together their organic forms had competed with the industrial legacy of new sculpture in the United States from Alexander Calder and David Smith, amongst others, in the mid-century. The British Council had, to an extent, used Moore’s work as a form of cultural diplomacy in the post-War period, culminating in the British pavilion at the Venice Biennale (1948, 1952) as well as contributions to the Festival of Britain (1951) and UNESCO commissions (1957-1958).

In considering his legacy Moore was cultivating neither image nor idea from scratch. His international profile had long been honed through a series of descriptive and, to an extent, narrative or ‘environmental’ portraits of the sculptor at work. These typically synecdochally charged portraits saw the sculptor’s hands become the protagonist of each photograph – affirming the universal aspect of direct carving and modelling upon which Moore’s prolific career had been built. By contrast, in Newman’s later portrait, the fundamental aspects of sculptural practice are brought to bear only through the inclusion of a wooden, as opposed to bronze iteration of Moore’s characteristic recumbent figure. Although the sculptor’s apron can be glimpsed around Moore’s neck, the sculpture functions largely symbolically in this image which uncharacteristically, for images of Moore, does not see him in the process of practicing his trade.

As such, this portrait aligns more closely with Newman’s latent intentions than some others: specifically, that of ‘looking to explain that person on a level that everybody would understand at most given moments.’ As opposed to taking the opportunity of creating a truly ‘environmental’ portrait of the artist at Perry Green – picturing Moore in the artist’s studio, surrounded by his tools – it is instead emblematic of the longevity of a formidable artist’s career, and presents on a deeper psychological level than the mere act of uniting artist, environment and methods of working

(By Emma Sharples)