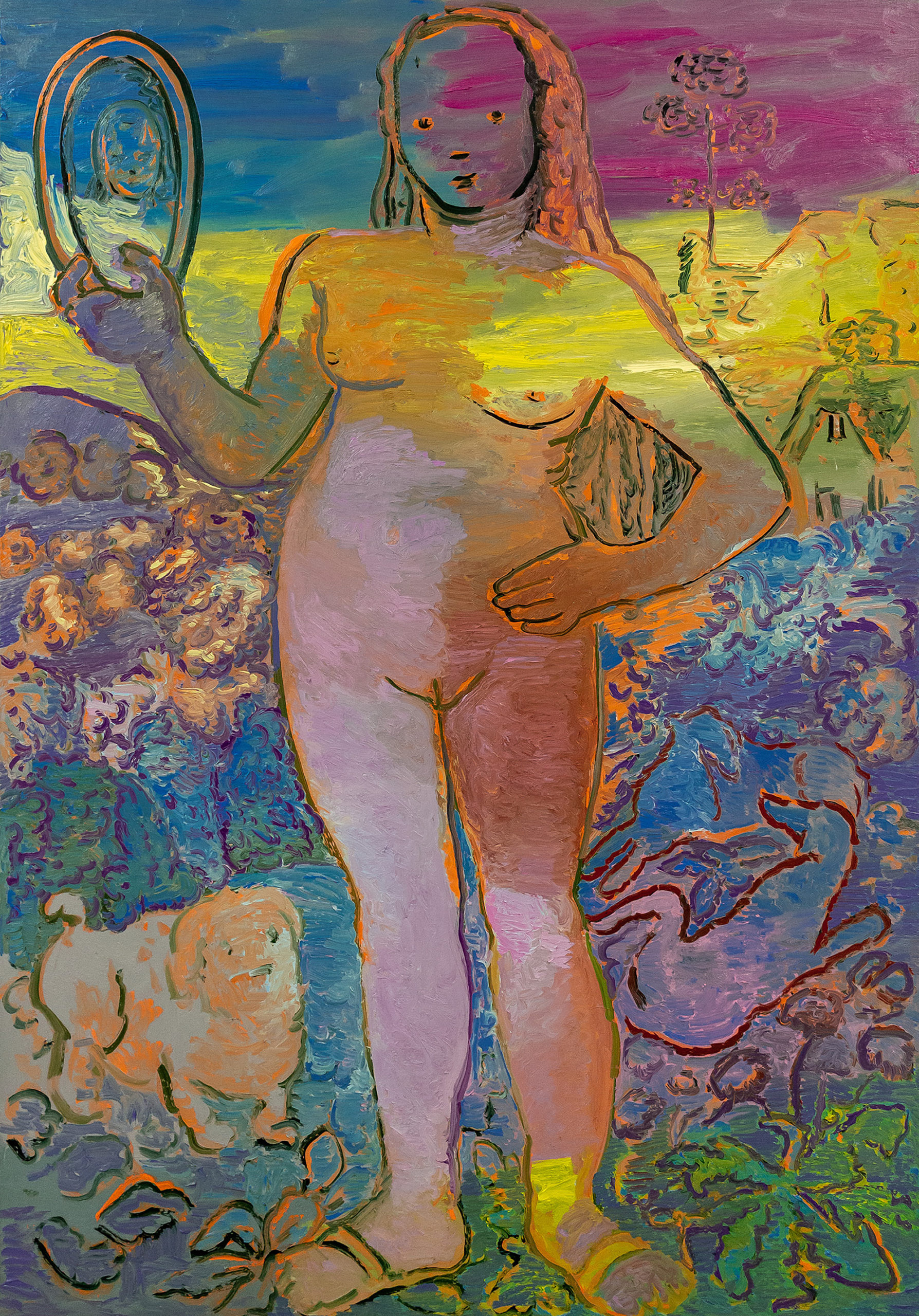

Delphine Hennelly, Laugh of the Medusa (2023)

In Delphine Hennelly’s work thickly laid paint is pushed energetically across the canvas in liberated strokes. Bold lines are created by scraping into the heavy surfaces, giving form to robust figures. Her lively colour palette, introducing juxtapositions and harmonies, creates an active and intricate tonal landscape. Hennelly likes to transition between ‘seduction and repulsion’ through her use of oil paint.

The title of the exhibition, Through Perseus’ Shield, is taken from the first painting in the suite of seven new works. It is a reworking of Hans Memling’s 1485 painting Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation. In Memling’s painting, the sinful vanity that requires salvation is a woman contemplating her reflection in a mirror. The 1485 painting intends to place constraints on a woman’s attempt to engage with her own self-image, to explore her identity. Hennelly sees this restriction as ‘akin to a form of oppression’ and her exhibition is, in part, a response to this patriarchal regulation of women’s desire for self awareness.

Delphine Hennelly, Through Perseus’ Shield, (2022)

In her investigation of this theme, Hennelly takes the motif of a figure, mirror in hand, as a departure point. Through repetition Hennelly seeks a subversive reconceptualisation of a woman’s desire for self-knowledge. In these figures the artist has recreated the personification of female vanity, but shows them engaging with their reflection with unashamed joy – the bright pastel palettes resonate with the figures’ dynamic poses, buoyant movements and classical costume. The melodramatic expressions of the figures in Blythe Spirit and Laugh of Medusa, particularly, amplify the wry self-knowing of the figures’ clever game.

The title of Hennelly’s exhibition refers directly to the Ancient Greek tale Perseus, the son of the virginal Queen Danaë and Zeus, high patriarch of the gods. The mortal King Polydectes wants to marry Danaë but her protective son gets in the way, so Perseus is sent on what is intended to be an impossible task: to retrieve the head of the gorgon Medusa. Medusa is a monstrous female creature, with snakes for hair and the ability to turn anyone who looks upon her to stone. As such a centre of power, her head has become a sought after trophy. Medusa and the gorgons live as outcasts – beyond the bounds of civil society. It is only by looking at Medusa through a mirrored shield, given to Perseus by the goddess Athena, that he can avoid petrification and complete his mission. Perseus presents the severed head to Polydectes who is himself turned to stone upon looking at it.

The symbolic significance of the tale of Medusa has been much discussed; the desire for Medusa’s decapitation has been interpreted as a manifestation of a male fear of castration. In turning men into stone, Medusa renders them immobile, that is, impotent; she threatens a separation of the male subject and his virility and the termination of male sexuality. Her decapitation amounts to a symbolic overcoming of castration anxiety. It was only through taking command of Medusa’s reflection, her portrait, that Perseus was able to subjugate her. Hennelly subverts this prevailing mythology: we view her figures through their own self-reflection, our view is the same which they see in the mirror.

The painting Laugh of the Medusa, takes its title from an essay of the same name by the French feminist Helene Cixous. Cixous argues that women need to find their own way of expression through their bodies and advocates for women to build strong self-narratives and identity, Hennelly imagines a mirror-world in which Medusa could enter the world of her reflection as opposed to being solidified by it, allowing an alternate outcome to the myth in which the male hero, threatened by the autonomy of a female gaze, is denied enacted violence and instead wrests agency to the female protagonist.

The mirror, the reflections therein, replication and repetition are central to Through Perseus’ Shield. Hennelly states: ‘in every repetition there occurs something specific, and therefore new, in the work.’ This understanding is grounded in the ideas of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze, and in particular his work Difference and Repetition. In the introduction, Deleuze presents the thesis that repetition acts in service of difference. When an action or an object is repeated, the relation between the original and the new is not, as one might expect, characterised by resemblance. Rather, repetition implies a displacement between the two, a distinction between the two: a difference. Relations of resemblance and equivalence express a ‘point of view according to which one term may be exchanged or substituted for another.’ Deleuze uses the examples of echoes and reflections, stating each is a repetition of some real object, a noise or a face, but is not exchangeable for that object – the echo can never precede the shout, the reflection can not move before the face does. Repetition establishes the fact that the two related objects are in-exchangeable: they are different.

Deleuze ideas are played out in the repetitions of figures that we see in Hennelly’s work. Each figure is a repetition of one archetypal figure, but none can be substituted for another. They share many qualities but through their similarities, their individuality is emphasised. Hennelly took as the starting point of this exhibition the repetition of a painting. Memling sought to restrict the moral bounds in which women live, while Hennelly, through repetition, creates something different – a space in which women may explore their identity and enjoy self-discovery.

(By Tom Winter)