The Bauhaus aimed to train the perfect designer through a multi-disciplinary curriculum that sought to raise design and craft to the same level as fine art. Through this, the Bauhaus’s founder Walter Gropius and his followers hoped to close the gap between art and life in order to combat a wider disillusionment with modernity. As art historian Hans M. Wingler surmises, ‘the synthesis of ideas consummated in the Bauhaus… was not simply a summary, but an eminently creative act.’ By way of a diverse structure that privileged artistic community over the traditional teacher-student relationship, the Bauhaus sought to encourage creativity by maximising the potential of new technical developments. Whilst American photographer Harry Callahan received no formal art school training, a period spent teaching in the New Bauhaus school in Chicago from 1946 can be used to elucidate his photography both historically and thematically.

While Callahan’s photographs, with their strict economy of line and carefully martialled compositions, bare much visual similarity to the abstract compositions of the Bauhaus school, Callahan’s work can also be considered with respect to Bauhaus ideals – particularly, those of his mentor and colleague, Moholy-Nagy. While the German Bauhaus’ primary focus was on architecture and design – with three iterations in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin – the New Bauhaus founded by László Moholy-Nagy in Chicago in 1937 placed photography at the centre of its curriculum. Moholy-Nagy had moved to Chicago that year at the invitation of Chicago’s Association of Art and Industry, to start a new design school which he named the New Bauhaus. Due to financial problems the school briefly closed in 1938, but in 1939 Moholy-Nagy re-opened the school as the Chicago School of Design. In 1944, the school became widely known as the Institute of Design, and in 1949 it became part of the new Illinois Institute of Technology university system: the first institution in the United States to offer a PhD in design. Moholy-Nagy invited Callahan to teach at the Institute in 1946.

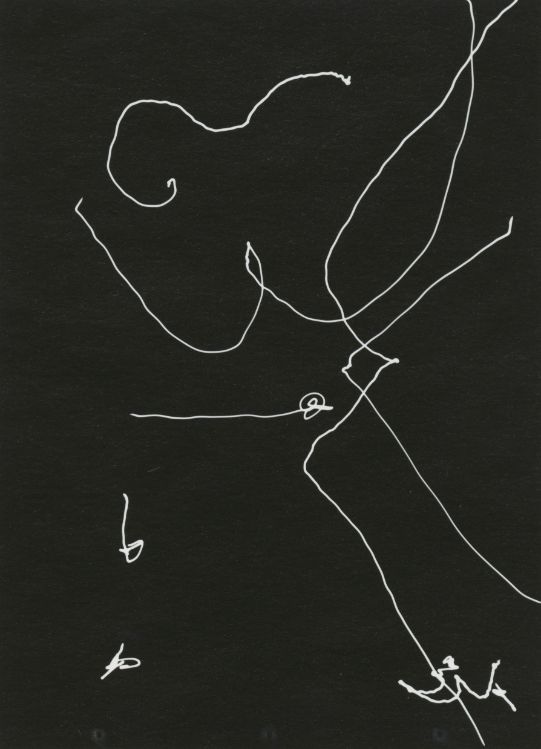

Moholy-Nagy’s thought was of thematic significance to Callahan’s work, particularly with regards to the maximising the aesthetic possibilities of photography. Known at the Bauhaus for his embrace of technology during his tenure, Moholy-Nagy went on to coin the term Neues Sehen, or, ‘New Vision’: he believed that the camera enabled the photographer to perceive the world even more clearly than the naked eye. This amelioration of the mundane can be seen in Callahan’s focus on the everyday ephemera of Chicago streets. His use of blurring, rotation, and double or triple exposure look to probe the parameters of perception, and allow the viewer to make new, visual connections. Callahan’s focus on nature, such as his 1943 work Sunlight on Water, the 1952 Ivy Tentacles on Glass, and Multiple Exposure Tree of 1956, all use the camera as a tool which abstracts the everyday to create strange composition in which the mundane morphs into the surreal. This profoundly technical approach to photography embraced the Bauhaus ideal of levelling fine art and applied art.

Further, the Bauhaus sought to close the gap between art and life through their curriculum which encouraged emotive design. In his book, Vision in Motion (posthumously published in his 1947, an account of his efforts to develop the curriculum of the Institute of Design), Moholy-Nagy similarly describes a Bauhaus ideal which sought to unite intelligent and emotional design. Instead of being ‘emotionally prejudiced’, artists should favour new opportunities encouraged by technological development over the empty conventions of the past. He argues that creative inertia can only be overcome through the union of ‘intellect and feeling’. For both Moholy-Nagy and Callahan, then, the camera was a tool that permitted the artist to create unity between art and life. Callahan’s photography embraced impassioned composition, as can be seen through the use of his wife, Eleanor, as a central component of his photography. This locus in particular, and the quiet sentiment that resonates from his photography, is testament to the marriage he created between ‘penetrative thinking and profound feeling’

(By Lydia Earthy)