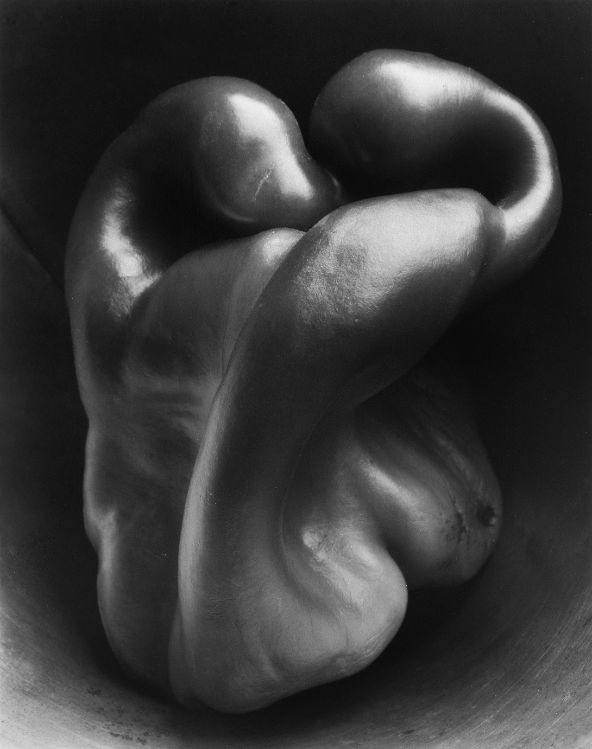

Edward Weston is synonymous with American Modernism, and rightly so – it was a key theme throughout his career reaching a peak in 1927 when he embarked upon a series of still lives of shells and vegetables that have become celebrated Modernist photographs. He was one of the great photographic innovators, who pushed the boundaries of the medium to new levels. He was an artist who found beauty in everything. Weston wanted clear lighting and, additionally, lighting that revealed the truth about an object. With his Pepper, 1930, for example, he agonised for days about how to light it, opting in the end for a dramatic lighting that accentuated its sensuous, curvaceous form.

As well as this, Weston deliberated a long time on the what background to use. At first, he used muslin, then white cardboard, but eventually decided on a tin funnel, which perfectly diffused light upon the pepper, and rendered it three-dimensional: “It was a bright idea, a perfect relief for the pepper and adding reflecting light to important contours.” By using an everyday object such as a pepper, Weston challenged ideals of photographic beauty. He later admitted: “I have done perhaps fifty negatives of peppers: because of the endless variety in form manifestations, because of their extraordinary surface texture, because of the power, the force suggested in their amazing convolutions. A box of peppers at the corner grocery hold implications to stir me emotionally more than almost any other edible form, for they run the gamut of natural forms, in experimental surprises.”