Untitled, Undated

In the autumn of 1994 Sandra Blow moved to St Ives, following the opening of the new Tate gallery in June of the previous year. The artist’s presence in St Ives, for the second time in her career, led to her renewed association with the school of lyrical landscape-abstraction which had flourished variously in the north of the Penwith Peninsula since the end of the Second World War. Although Blow never signed a manifesto, nor was she ever formally considered part of a group, her friendships with middle-generation St Ives artists including Roger Hilton and Patrick Heron, as well as her inclusion in the 1985 Tate exhibition St Ives 1939-64: Twenty-Five Years of Painting, Sculpture and Pottery, placed her firmly within a network of artists rooted in the communities of West Cornwall. In reality, however, the associations of this milieu offer only an abridged version of a career which was, in its largest part, centred around London.

Blow first left for Cornwall in the spring of 1957 at the invitation of Patrick Heron, spending only a year there just as her career was taking off in both London and New York. Blow’s first year in Cornwall was spent living in a cottage at Higher Tregerthen, a largely inland experience characterised by the granite moorland and boulder-strewn coastal fields around Zennor. By contrast, the period 1994-2006 brought with it the possibility of working, amongst other locations, in the beachfront Porthmeor studios. As a result, Blow’s late work picked up a greater sense of the sea, its geological complexities, and the mess of reliefs and ridges cast in the sand around her studio. In her blanket association with St Ives, as the writer and art historian Michael Bird observes in his 2005 monograph of the artist, Blow’s critical reception has overlooked the nuance of two finite and contrasting periods: both of which form part of a more variegated artistic presence than emerges at first glance.

In a similar vein, assumptions regarding the influence of Alberto Burri, whom Blow first met in the late 1940s whilst travelling in Italy, serve to critically define the artist’s earliest abstract works. Until recently it was accepted that Blow uniformly adapted Burri’s Art Informel style – which included the use of materials such as sacking, wire, ash and plaster – over the course of their relationship. In fact, as Bird notes, Blow’s early interest in abstraction manifested through discussions with the painter Nicholas Carone in Rome, who had attended the influential German-born American painter Hans Hofmann’s classes in New York. Equally formative were the colour, form and composition of early Renaissance frescoes by Piero Della Francesca, Giotto and Masaccio, as well as Art Brut’s contemporary handling of non-fine art materials in Paris, where Blow and Burri later travelled in the winter of 1948-1949.

Burri’s working practice largely fitted the masculine narrative of post-war abstraction, now critically examined through exhibitions such as Making Space: Women at Postwar Abstraction (MoMA, 2017). A former military doctor, Burri often worked solitarily and conformed to the formalist critical discourse of masculine vitality, authenticity and freedom precipitated by descriptions of the Abstract Expressionists and their successors in the United States. Blow was less easy to characterise, later working on as monumental a scale as the New York school, but with an altogether more considered attitude towards plastic space. Unlike her American contemporaries, careful composition quietened loud, gestural abstraction and there remained a firm coherence in her treatment of pictorial space. What persisted was an emphasis on composition and pure abstraction, as opposed to any overarching critical narrative propagated by her practice or lifestyle.

Blow’s lack of finite group identity was further problematised by her inclusion in Lucy Lippard’s curation of the Hayward Annual ‘78, the first Arts Council-sponsored exhibition in Britain organised by women and showing predominantly women’s work. Blow showed five paintings and two groups of paper collages, but their striking abstraction left little critical space for feminist interpretation, particularly when considered alongside the nascent conceptual work of artists such as Mary Kelly, who showed an installation as part of her ongoing work Post-Partum Document (1973-77). Although at times Blow’s work approached the political, she remained, contrastingly to contemporaries Gillian Ayres, Patrick Heron and Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, unwavering in her commitment to pure abstraction. It was an allegiance which was to become challenging through the later 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, as abstraction fell out of fashion and British Pop and Conceptualism came to the fore in the work of the Independent Group amongst others.

Whilst it may be the changing critical fortunes of abstract art to which Norman Rosenthal was referring when he wrote of Blow’s ‘particular and difficult to maintain path of abstraction’, it was more likely a reference to the artist’s extraordinary working practice – yet another factor which left Blow’s critics at a loss as to where to place her. Blow’s works are characterised by their diachronic existence: taking shape formatively over extended periods, during which time the artist would continue to revisit and rework her canvases. Whilst reproductions of Blow’s work can have the appearance of flat, abstract paintings, this impression belies a complicated process of surface-formulating collage, as in Relievo (2005).

The process of collage meant that Blow was able to envisage multiple iterations of a composition before committing the final design to canvas. In Brilliant Corner (1993), there is a sense that the brightly-coloured forms – those which anchor the composition – have only come to be tempered by the work’s darker ground through a considered process of evaluation. Blow would cut out shapes in lining paper before stapling them to bare canvas: these were mobile objects to be manipulated until a stable composition was reached, after which time she would paint in their presence. At each stage photography would be used – in the form of Polaroids – both to document Blow’s process but also to facilitate the rotation of the composition when a canvas was too large to be turned on its side.

Despite the meditative nature of her process, Blow remained a social artist. She valued the opinion of her contemporaries and would readily take criticism on board – although her work courted little – reworking her canvases through to momentary resolution. In 1960 Blow moved into Sydney Close, a large studio off the Fulham Road in London, where her neighbours included the artists Rodrigo Moynihan, Jim Dine, Michael Andrews, and Robert Buhler. Moynihan in particular was a great friend, whom Blow routinely invited in to give critique on her work. A year later she joined the teaching staff at the Royal College of Art and found a similarly productive social atmosphere at play. Amid a developing retrospective criticism of post-war abstraction, exponents of which often appeared singularly, caught in an internalised struggle with their medium, Blow chose instead to actively cultivate creative relationships and extend the dialectical model of her practice beyond the studio walls.

It is the artist’s late works which bear the fruits of this rarefied but continually evolving process. Distinguished by two defining characteristics – scale and a distilled use of colour – the inception of this period can be traced to the spring of 1968. Blow’s second solo show at the New Art Centre had coincided with a double feature in the Women’s Page of The Times presenting Blow alongside Brigit Riley as painters who have achieved world recognition. Critics were struck by Blow’s charged use of colour in the NAC exhibition, a trait which Michael Bird sees as partially engendered by the artist’s time spent teaching at the RCA, where R. B. Kitaj and David Hockney had been amongst the students, and partly by Blow’s recent adoption of the acrylic emulsions so favoured by colour field painters Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler and Mark Rothko.

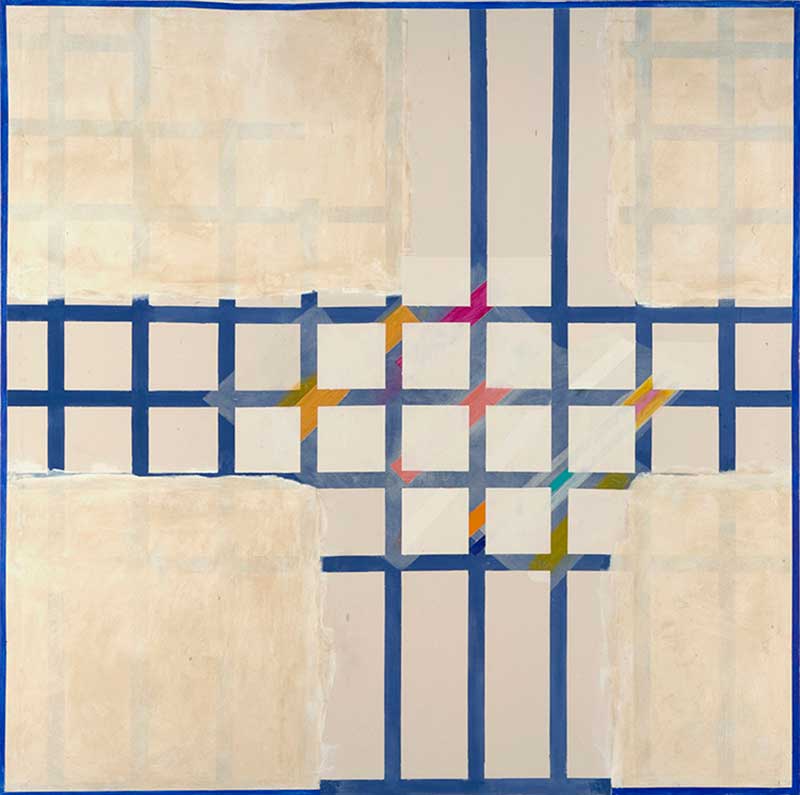

A year after the New Art Centre show, the artist completed her first truly large-format painting, Green and White, executed on a canvas which was three metres square. Later purchased by Tate, the work’s balanced composition and emboldened use of colour were emblematic of the direction Blow was to pursue throughout the 1970s: in particular between her election as RA associate in 1971 and full Royal Academician in 1978. Both Untitled (1972) and Untitled (c.1975) demonstrate Blow’s ongoing investigation into scale, colour and composition during this period. The works are anchored by the strong diagonal presence evident in Green and White, but where Untitled (1972) favours a ground of flat colour in its use of oil, Untitled (c. 1975) sees Blow exploit the watercolour-like properties of acrylic to create large areas of varied saturation, more gestural in their facture.

The RA’s endorsement of the artist was central to Blow’s ability to pursue experimentation, particularly during periods of ill health and mounting London rents throughout the 1980s. Blow was freely able to explore the possibilities of three-dimensional projection in her work, as well as the use of unorthodox materials such as PVC and Perspex, safe in the knowledge that there would be space for her work to be exhibited. In the later 1980s, Blow investigated a more-actioned orientated process, producing works such as Vortex (1986) and Vivace (1988). Vivace was hailed by Victor Pasmore and the contemporary critic Norbert Lynton as ‘astonishing’, with its curving arc of paint forcibly thrown against the canvas. This form, nevertheless, was underwritten by a series of collage elements, demonstrating that the artist’s approach remained a concerted process: procedural, as if the work’s essence existed not in the moment of its completion, but over time.

The reconciliation of action and deliberation – two seemingly opposing forces – would later be mirrored in the tension which Blow’s works of the 1990s and early 2000s maintain between neutral and vivid colour. Both Quasa Una Fantasia (2004), and Touchstone 2 (2005) erupt with diagonal strokes almost neon in tone, amid large expanses of paler ground. This rarefied use of colour on a monumental scale had its antecedents in Blow’s colour work of the 1970s, as well as her later experimentation of the 1980s, but cannot be characterised as singularly gestural or geometric. Nor do Blow’s canvases of this period conform discretely to the school of St Ives, where the artist had returned to work in 1994. Resolute in their refusal to be succinctly assessed by school or style, the nature of Blow’s late work eludes definition as purposely as her oeuvre when considered as a whole. As such, perhaps it is recognition of the artist’s process as a dialectical model, concerned with the resolution of opposing forces – a continual push and pull – which best captures Sandra Blow’s unique and enduring contribution to 20th and 21st century abstraction

(By Emma Sharples)