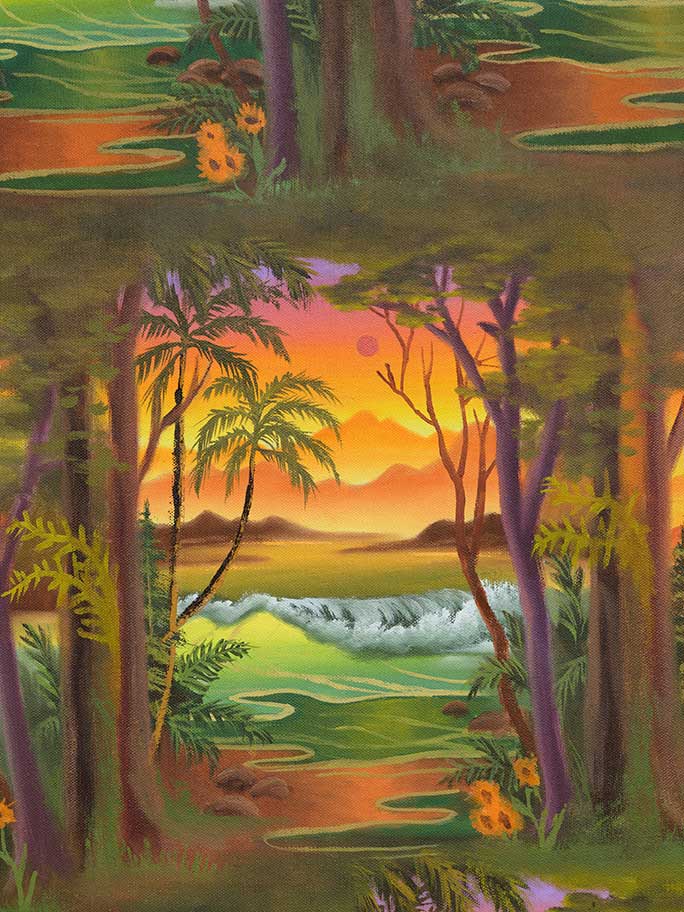

Neil Raitt, Papaya Palms (Emerald Waters 100 Edit), 2024 (detail)

A whiff of salt-air, sunscreen, and sand… a repeated vignette stutters across Papaya Palms (Emerald Waters 100 Edit) like a burst of photos taken to fill the last shots of a disposable camera on holiday — each one idyllic, vibrant, and seemingly identical frame by frame. While such uniformity between each scene and the smoothness of the canvas may point to a digital render or print, Neil Raitt’s paintings are made analogue and feature small discrepancies between each frame to prove his own hand. Championing kitsch and hyper-digital aesthetics with paintings recalling stamping tools and glitching, Raitt renegotiates the potential for craft and outsider art in historic high-brow genres.

Landscape painting, as it was established by the Academie des Beaux-Arts, was rigidly defined by the painter’s use of the foreground; any large subject central to the scenery would disqualify the piece from the genre. When meeting this criteria, landscape paintings often served transcendental and allegorical functions in Western art, notably in the Scottish Enlightenment, where paintings of towering mountains and unruly seas were seen as a vehicle, transporting the viewer to the sublime. Contrastingly, with the cascading repetition tessellating across the canvas, Raitt instead reasserts the landscape itself as the subject of Papaya Palms (Emerald Waters 100 Edit). His landscapes don’t operate as backgrounds — either to a human subject within the space or to a metaphysical experience. Instead, Raitt celebrates the landscape through its new-found subject-hood, turning the rigidly defined genre on its head and exploring the possibilities of landscape painting for contemporary global audiences.

The hierarchies of painting are again subverted by the unreality of Raitt’s imagined environments. Rather than sharing the wonder of a distant port like 1900s Shanghainese souvenir oil paintings or establishing a national identity through reminiscing upon local ruralities in Netherlandish works in the 1700s, Raitt’s landscape paintings aren’t rooted in real topographies. Instead, they speak to the feeling of ‘hiraeth’, a Welsh word describing a longing for a place that no longer exists or never existed at all. Using vibrant colouring similar to a souvenir card from a trip to Hawai’i or a faraway tropical paradise, Papaya Palms (Emerald Waters 100 Edit) generates a universal nostalgia for an unreal place; an impossible climate which grows both sunflowers under the shade of beach-side palm trees and creates oceanic waves undulating in front of a mountain range in close proximity.

The familiarity and impossibility of the scene appeals the painting to a wide audience, as while it feels like a poignant memory for every viewer, no one person can have a more intimate recollection of the fanciful rippling sands and waving fronds shown in Papaya Palms (Emerald Waters 100 Edit). Such accessibility recalls Bob Ross, a long-standing source of inspiration for Raitt, who opened up landscape painting to the masses. Reiterating upon the goal of his muse, the works in Raitt’s exhibition Floating Lands free realism and landscape painting from their historic genre through his love of vibrancy, repetition, and kitsch

(By Teddy Woods)