In 2007 John Maloof paid $400 for a box in a blind auction in Chicago. An estate agent and flea market frequenter, Maloof was hoping to find historically interesting photographs of Chicago for a book he was writing about the city’s architecture. He was president of the historical society on Chicago’s Northwest Side that was dedicated to promoting awareness of the area’s underappreciated charm. He needed over 200 photographs of the area for the book so had been scouring local auction houses in search of old pictures. Visiting RPN Auctions he found a box of photographs showing Chicago in the 1960s. He was unable to properly view the contents of the box but bought it anyway. Disappointed that the negatives were not useful for his project, he stored it away and forgot about it.

Two years later, however, Maloof’s interest in the negatives was piqued and he set about scanning them into his computer. As a vast library of compelling street photography emerged from the box, Maloof began to realise the significance of what he had found. Maloof had little experience of photography but the negatives captured his interest and he took his own camera out into the street to emulate the mysterious photographer. He took a course on photography and set up a darkroom in his attic. He had, very quickly, become obsessed with photography and with the previous owner of the box – Vivian Maier.

The only mention of Maier found through an internet search was a brief obituary. This led Maloof to several of the families for whom Maier had worked as a nanny. Tragically Maier had died only shortly before Maloof had begun attempting to find her. Finding himself an unlikely custodian of this vast, important archive, Maloof has dedicated his life to preserving and promoting Maier’s work. The contents of Maier’s five storage lockers had been sold (without her knowledge) when she had failed to pay the rent. A local auctioneer, Roger Gunderson, bought the lockers’ contents for $250 and split the contents up into smaller lots to sell on. Maloof subsequently became the owner of one of these lots.

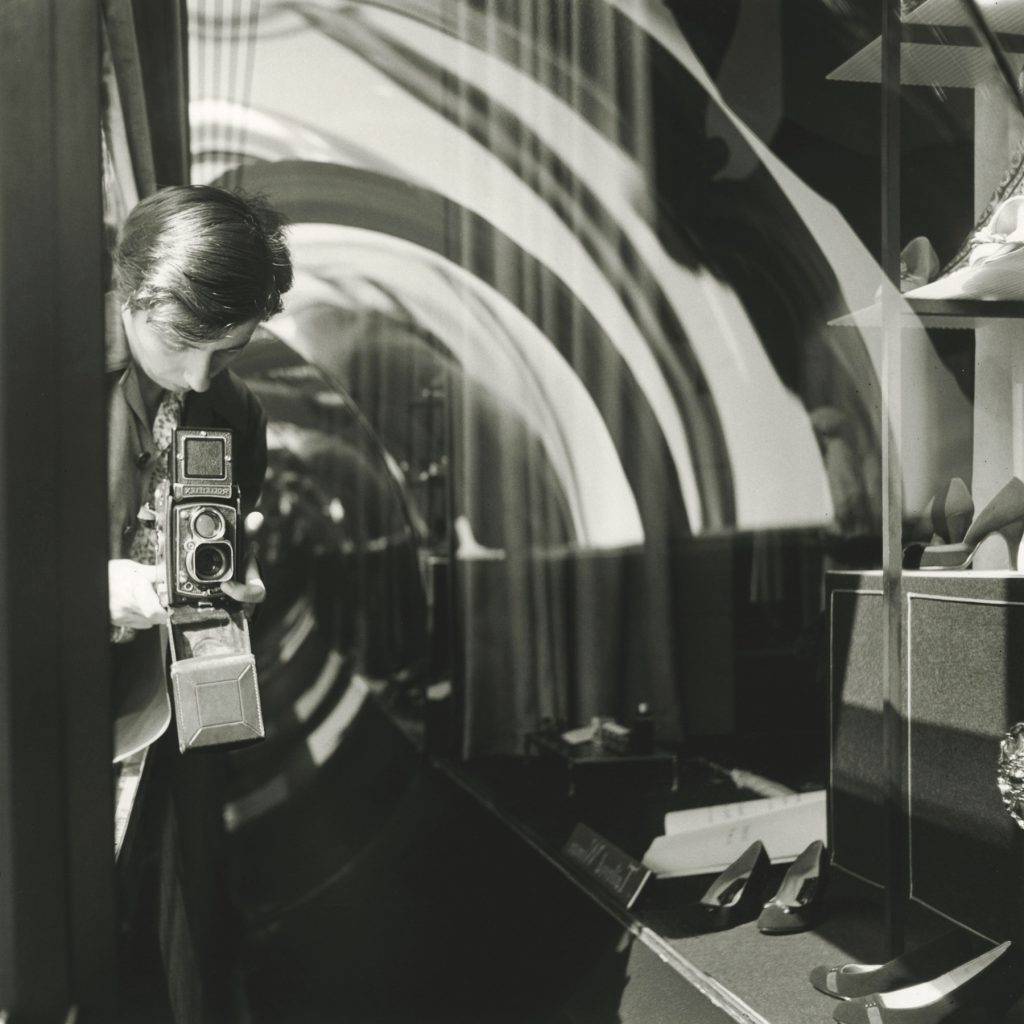

Self-Portrait. Vivian Maier

Maloof set about archiving Maier’s work and it began to garner interest when he posted some of her photographs on the image sharing website, Flickr. Maier quickly became an internet phenomenon as thousands of people responded to Maloof’s post, astounded by the obvious talent and huge output of the unknown photographer.

Maloof has since traced many of the families by whom Maier was employed. Accounts of her personality are varied but all agree on her solitary nature and obsession with taking photographs. Some of the children she took care of recall their time spent with her as idyllic whilst others remember her as severe and difficult. Some considered her secretive and unwilling to promote her work whereas others thought her deeply frustrated. Many of the children she looked after remember her strong will, distinctive heavy-footed walk, old-fashioned clothing and men’s shoes. She liked reading about politics and going to the movies, but always on her own.

Although two other collectors – Ron Slattery and Randy Prow – also purchased selections of Maier’s photographs at the same time as Maloof, he has since acquired 90% of the estate. He now owns an extensive archive including many of Maier’s cameras, over 100 8mm movies, 3,000 prints, 2,000 rolls of film and 100,000 to 150,000 negatives. Jeffrey Goldstein bought another significant body of Maier’s work from Prow in 2010 but subsequently sold it to a Canadian gallery.

The international press has shown unrelenting fascination with Maier’s story and she has become a household name. The New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman has called her one of ‘the great American mid-century street photograpers’ and she is frequently compared to the giants of twentieth-century photography including Diane Arbus, Henri Cartier-Bresson and André Kertesz. Maier’s photography has gained its reputation not only because it is a fascinating history of urban America, but also because it is a triumph in psychological study. Exhibitions of Maier’s photography have been held in museums and galleries all round the world. Several books have been published about her life and works whilst two documentaries have been made. The reclusive nanny’s lifetime of work has been retrieved from obscurity and placed in the canon of twentieth-century photography

(By Giles Huxley-Parlour)