Donald Sultan: Dark Objects, 2019

This text was commissioned on the occasion of Donald Sultan’s 2019 solo exhibition, Dark Objects.

I first came across Donald Sultan’s work in the early 1980s when I was briefly head of Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s in New York and Donald was showing at the Blum Helman gallery in a smart new space on 57th Street, then the hub of the contemporary New York art world. I was immediately impressed by the big, dark ‘disaster’ paintings Donald was working on at that time, but also the range of subjects that caught his pictorial eye, from lampposts and factory chimneys to delightful still-lives of lemons and flowers. All depicted in a simple dramatic outline on dark pitch-black mat surfaces, which struck me as a whole new way of making paintings. Donald was in his early thirties and had an almost immediate success with the American critics and collectors. There was something about his work that reflected the zeitgeist of the times. America was beginning to recover from the wounds of the Vietnam War but the horror of that war still lingered in the mind and found expression in such films as Apocalypse Now. It was as if peace of a sort had returned to America but the fires had still not been quite put out.

Economically, America seemed poised between the decaying old industries of the rust belt and the new high tech industries still to come. In art, too, American taste had moved on from the turbulence of Abstract Expressionism, to something cool, minimalistic, designed and media driven. Donald’s paintings of fires and disasters struck a nerve and although he was not the first American artist to tackle this kind of subject matter – Warhol, prescient as ever – had painted a whole series of disaster paintings back in the ‘60s – Donald’s paintings brought a new pictorial intelligence and sense of design to the subject, and a new way of constructing paintings using tar and paint on tile and masonite, a technique which seemed to mirror the changing economic landscape. His materials seemed both coarse and industrial, but also modern and ultra cool.

Soon after one of these shows at Blum Helman I met Donald and began to spend time with him down at his studio and in the exciting new restaurants then opening in SoHo (South of Houston) where Leo Castelli and other art dealers liked to concentrate before the New York art world went westwards to Chelsea. I was immediately impressed how articulate he was, how organised, how ambitious, how many ideas he had, how much self-confidence he possessed. He spoke with a laid-back, slight Southern drawl (he was born in Asheville, North Carolina and grew up in the South) and he viewed the world with a wry, perhaps slightly cynical, point of view. I could see how this energy and intelligence related to his work. My enjoyment of Donald the talker and Donald the picture maker must have struck a chord and I was flattered to be asked to write an essay for a landmark show he had in 1987 at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art. I was equally flattered some thirty years later to get a call from Donald to tell me he was having a show in London and would I supply a few words for the catalogue.

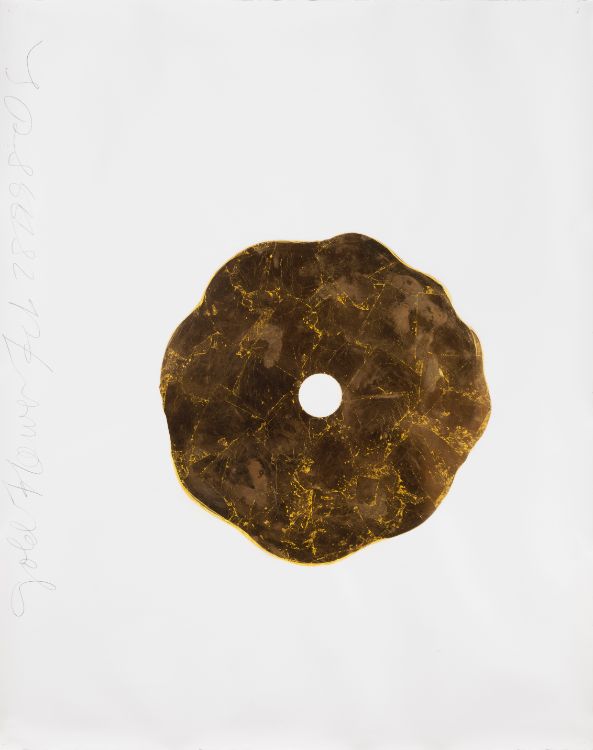

Golden Flower, 23 October 1998

Thinking afresh about his work, it more than stands the test of time. It is really wonderful for those who have not had the opportunity before to see some of the early works for the first time, alongside more recent work. In the States recently there was a museum show of his ‘disaster’ paintings organised by the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, which travelled to the Smithsonian in Washington among other destinations. Here in London we now have the chance to see one of his best ‘disaster’ paintings from the mid 1980s – Lines Down November 11, executed 1985. Presumably the subject was inspired by some natural disaster, perhaps the aftermath of one of many hurricanes that sweep through the East Coast of America. It does not really matter what incident inspired this work, however, as you immediately sense something bad has happened and you are immediately struck by the powerful diagonals of the composition (perhaps an echo of Franz Kline’s great black and white expressionist paintings) and the pitch-blackness of the industrial wreckage silhouetted against a pale acid yellow sky. Here is a painting with real ‘umph’.

It seems now that these disaster paintings from the ‘80s almost anticipate some of the awful things that have happened in the world we find ourselves living in today. As I write, the fire that engulfed Notre Dame has just been put out, bombs have destroyed churches in Columbo leaving charred wrecks, and gunfire has ruined lives in mosques in New Zealand. Without wishing to sound too portentous we seem to be living in an age of disasters – and the awful thing is that we have almost got used to it. It was as if the great wars, which brutalised lives in the past, have been replaced by disasters, natural and man-made. But the images which shock and horrify us today stay in the mind for a day to be replaced by something equally horrible tomorrow. Donald’s paintings, however, are there as a permanent record, a sort of modern momento mori for us to contemplate.

But it would be quite wrong to think of Donald as just a painter of disasters. He has far too vivid an imagination to be stuck with one subject. Away from the studio he strikes me as a bon viveur, even a flâneur, in the way Baudelaire admired the modern artists of his day. He enjoys a well-made handcrafted pair of shoes and a well-cooked entrecôte like the best of us. And this enjoyment of life, of talk, of hanging out with friends and shooting the breeze, is reflected also in his paintings of fruit and flowers, and I am glad to see that some of these are included in this exhibition. And this restless energy which I first noted in my essay of 1987, allied with a very strong work ethic, has allowed him to produce work in different mediums and different sizes over a long period but all realised with confidence, with discipline and an elegance which is hard to pin down but something like the elegance of a Japanese woodcut.

I hope this exhibition at Huxley-Parlour will kindle a new enthusiasm for Donald’s work. It has certainly rekindled mine.

(By Ian Dunlop)