I need to listen to my paintings

Catherine Long2026

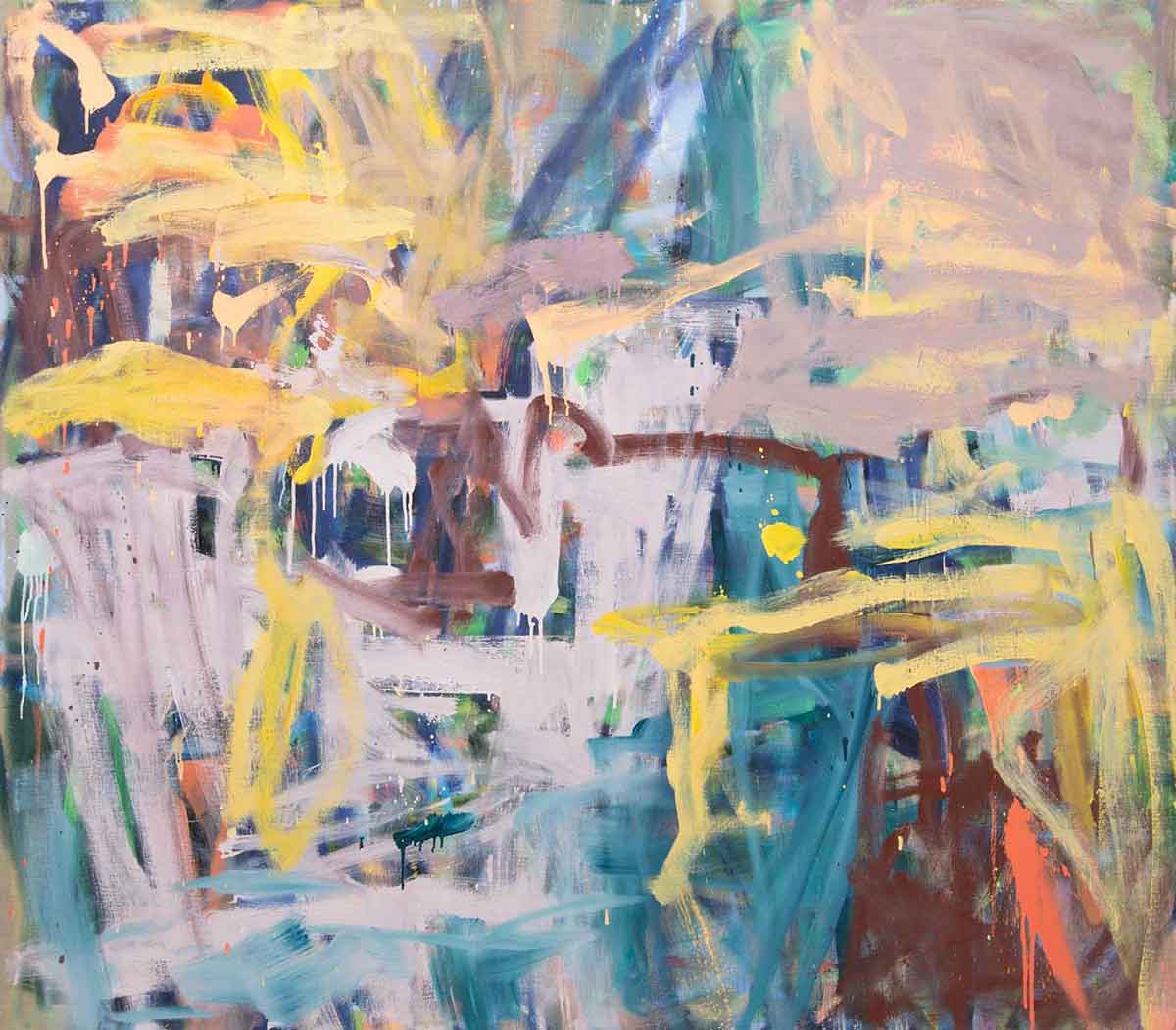

Catherine Long, Falling Into Dust, 2025

This text was commissioned on the occasion of Catherine Long’s solo exhibition, After the Fire. The text is written by Tom Morton, writer and curator.

The philosopher Jaana Parviainen defines kinesthetic empathy as ‘a re-living or epistemological placing of ourselves “inside” another’s kinesthetic experience’. In somewhat plainer language, we might describe it as our capacity to understand and share in somebody else’s life and feelings by observing them in motion. One everyday example of this phenomenon is the way we hold our breath when we watch a tennis player serving at match point, or a character in a horror movie opening a creaking cellar door. Kinesthetic empathy will also be familiar to anyone who has attended a dance performance, and found the dancers’ movements echoing in their own body, creating sensations of muscular effort and physical grace, coiled tension and sudden, ecstatic release.

Might we still experience this form of empathy if what we’re witnessing is not a living, moving being, but rather a static, abstract image? This is a question at the heart of Catherine Long’s art. She is a painter whose practice is deeply informed by her background in somatic dance (a discipline that emphasizes the dancer’s internal physical perception and personal embodied experience), and on one level, her paintings may be said to trace the movements she makes in her studio, as she applies pigment to the surfaces of her customarily large-scale canvases. Long, who often works on multiple compositions at the same time, has described how she will ‘take a moment to dance’ as she switches between one emerging image and another. Beyond selecting the size of her supports, and creating an initial colour palette, nothing is pre-planned about her painting process. It is rather, as she has said, ‘instinctive’, and involves not only an awareness of pictorial space, but also how she inhabits physical space as she labours — the reach of her arms, the bending and straightening of her knees, feeling the pull of gravity on both her body and her paint.

Significantly, Long has likened painting to contact improvisation, a postmodern dance practice in which two or more dancers explore the interplay of their mass and momentum. When she commences work on a canvas such as Amidst the Burning Breeze (all works 2025) she paints at speed, making emphatic gestural marks, allowing her pigments to run, to drip, to exercise their material autonomy. Eventually, though, comes a moment of what she terms ‘recognition’, when the image coheres and she slows to a calmer pace. The artist has said ‘I need to listen to my paintings’ so that they might ‘reveal themselves to me’. Making art is, for her, ‘a relationship’.

The title of Long’s triptych Still Waters appears to contradict its surface turbulence. Across the work’s three panels, ribbon-like strokes of inky purple, pale blue and calamine pink arc, dip and pivot, sometimes thinning to an almost graphic line, sometimes luxuriating in their own painterly thickness. Much earthier, and more grounded, are the brown forms resembling primitive shelters fashioned from sticks, which sit above and below a murky, pond-green horizon line. Is this, then, a landscape of sorts? Something deep-rooted in our collective cultural memory, or even perhaps our bodies, tempts us towards this conclusion, only for it to be dispelled when we consider that Long is an artist who looks less to the example of, say, John Constable than she does to pioneering female Abstract Expressionists such as Joan Mitchell, Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning. Nevertheless, the sense remains that Still Waters is not so much an image as a space in which we might immerse ourselves. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously described architecture as ‘frozen music’, highlighting the two art forms’ shared principles of rhythm, harmony, proportion and structure. Similarly, for Long painting is something akin to frozen movement, although so dynamic are her marks that looking at them, we half expect that they might at any moment thaw.

The natural world is again evoked in the title of Long’s work Unruly Sun. Here, we see not a glowing, celestial orb, but what might be its reflection, smashing into a pool or puddle, where it fragments into staccato yellow flashes. While the artist’s paintings possess an undergirding order, they abjure the tidy, the bounded, the superficially whole. In Origin of Being, a vertical form seems to coalesce in the centre of the composition – a rare occurrence in Long’s work. Here, graphic white lines summon a teetering stack of irregular squares and rectangles, resembling a Cubist still life, or a freehand sketch of some 4-dimensional geometric solid. These lines, however, cannot hope to contain the intense turquoises, primroses and deep, midnight blues that explode across the canvas. Looking at this painting, I get to thinking of the Big Bang the setting in motion of everything we know, and everything we are.

Back, for a moment, to kinesthetic empathy. Long’s project is not autobiographical in any ordinary sense of the word, and the lived experience she communicates through her paintings is never narrativized. Rather, what we’re asked to connect with is how it felt to inhabit her body while she was making a given work, something so complex, so enmeshed with everything from her emotional weather to the cycle of the seasons to the current political climate, that it would be difficult to express through any other means. Witness This Skin I’m In, a painting in which pigments have been built up like dermal layers, or geological strata, and then inscribed with rapid, energetic marks that resemble letters in an alien alphabet, or ciphers in some unbreakable code. Perhaps this is a work about how we humans – encased in our own skins, our own minds – crave genuine communion, but are always frustrated by the limits of descriptive language. If so, and as Long’s practice suggests, we should attend not only to what other people say, or write, or even depict, but also to how they move through the world, and the abstract traces they leave behind. On the most fundamental level, this is something that our bodies understand.

(By Tom Morton)