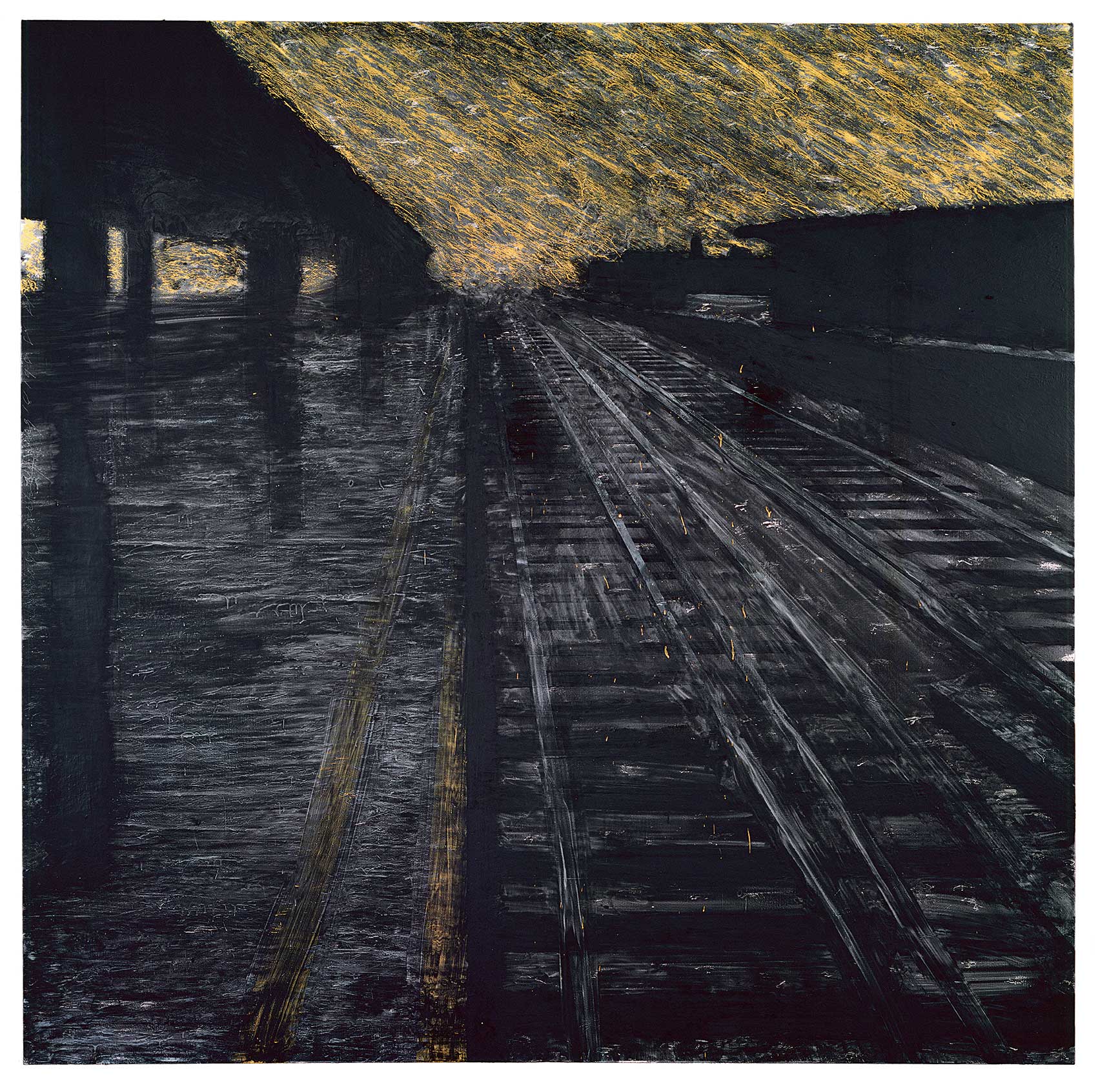

Herndon Railway, 18 August 1988

In the later 20th and 21st centuries, disaster as a phenomenon has been both brought closer, and made more distant, from the individual. Whilst technology’s ubiquity allows us to learn about global disasters instantly, the very same multiplicity serves to render each tragedy more normalised than the last. Made during the 1980s, Donald Sultan’s monumental Disaster Paintings speak to this developing phenomenon, offering specific renderings of individual traumas as well as generalised representations of disquiet and dread.

The Disaster Paintings make use of tar and latex on linoleum tile, focussing heavily on materiality and imbuing Sultan’s works with a depth of surface unparalleled across the artist’s larger body of work. Taking news stories about disastrous industrial and urban events – such as freight train derailments or warehouse fires – as their source, the hardy structure of Sultan’s paintings appears to comment on their subject: specifically, the dichotomy between robust structures – trains, industrial scaffolding, industry – and the ephemerality of disaster. Speaking in interview, Sultan has described their subject as impermanence: ‘The largest cities, the biggest structures, the most powerful empires—everything dies. Man is inherently self-destructive, and whatever is built will eventually be destroyed… That’s what the works talk about: life and death.’

In a similar vein, Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster prints, made from 1962 onward, capitalise on the disparity between image and surface. However, where Sultan privileges a physical, narrative materiality, Warhol’s series epitomises postmodernity’s emphasis on the reductive reproducibility of surface. Co-opting press images from publications including the famed LIFE magazine, Warhol would repeat each image up to sixteen times within each composite work. The artist’s screen-printing technique served to distort the grim details of the images, as well as to desensitise the viewer through overexposure. In this way, the cultural critic and theorist Fredric Jameson saw Warhol as the archetypal example of postmodern flatness, arguing that whilst the content of Warhol’s work – death and disaster – should cement a powerful, political statement, instead the works indicate ‘the emergence of a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality in the most literal sense.’

Sultan’s practice subverts this muted take on disaster. To consider Lines Down, 11 November 1985, is to be confronted with a crucible of texture, colour, and darkness. Mounted on wooden structures akin to shipping crates, the paintings are thick, obscure, cracked, and heavily-wrought: a reflection of the industrial heritage of the lofts within New York’s Tribeca in which the artist was working. The viewer is able to discern, upon close inspection, the shape of cars; a road; a canopy of wires, beams and industrial structures matting the sky above. The surface is mottled with vein-like tributaries of latex, staining the surface yellow and black. Their size dwarfs the viewer and, without inflating any explicit societal or political message, forces them to come to terms with the event depicted. Whilst Warhol’s works depict disastrous events as muted and inconsequential, Sultan incorporates the material of industry into the very works which portray its decline. As such, where Warhol’s Death and Disaster prints can be understood as a comment on the waning impact of tragedy, Sultan’s can be understood as making disaster disastrous again