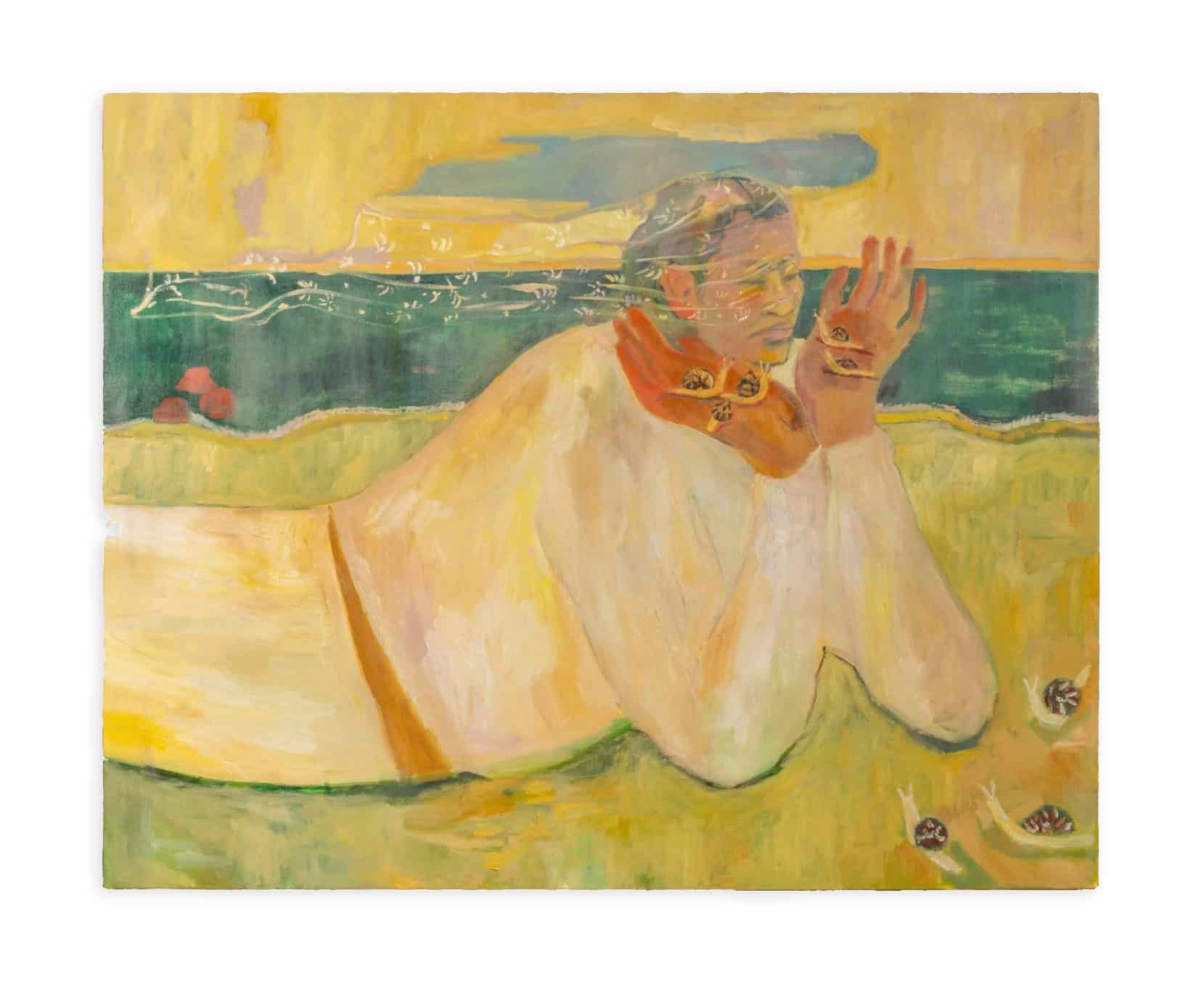

Todo se repite en esta existencia (Everything is repeated in this existence), 2024

This text was commissioned on the occasion of Lorena Torres’ solo exhibition, El Milagro es la Pereza de Díos. The text is written by Maria Adelaida Samper, an independent curator and researcher based in Bogotá, Colombia.

In El Milagro es la Pereza de Dios – which takes its name from Fernando Pessoa´s The Book Of Disquiet – we find ourselves immersed in glimpses of Lorena Torres’ construction of her own personal mythology: her particular view of Caribbean culture, and its long history of magic, illusion, and entanglement with the marvellous. This exploration feeds from the mysteriousness that she finds in the gaps of everyday life, and from the possibilities she encounters through experimentation with the medium of painting, as well as a constant dialogue with the realm of poetry and her own subconscious. Torres’ means of expression is clearly linked with the tradition of magical realism; but, in the same way that there was a tense relationship between European Surrealism and Latin American magical realism, her work is not easily placeable under any of those umbrellas. Her modes of representation seek to not only honour her heritage but also question it and make it more complex.

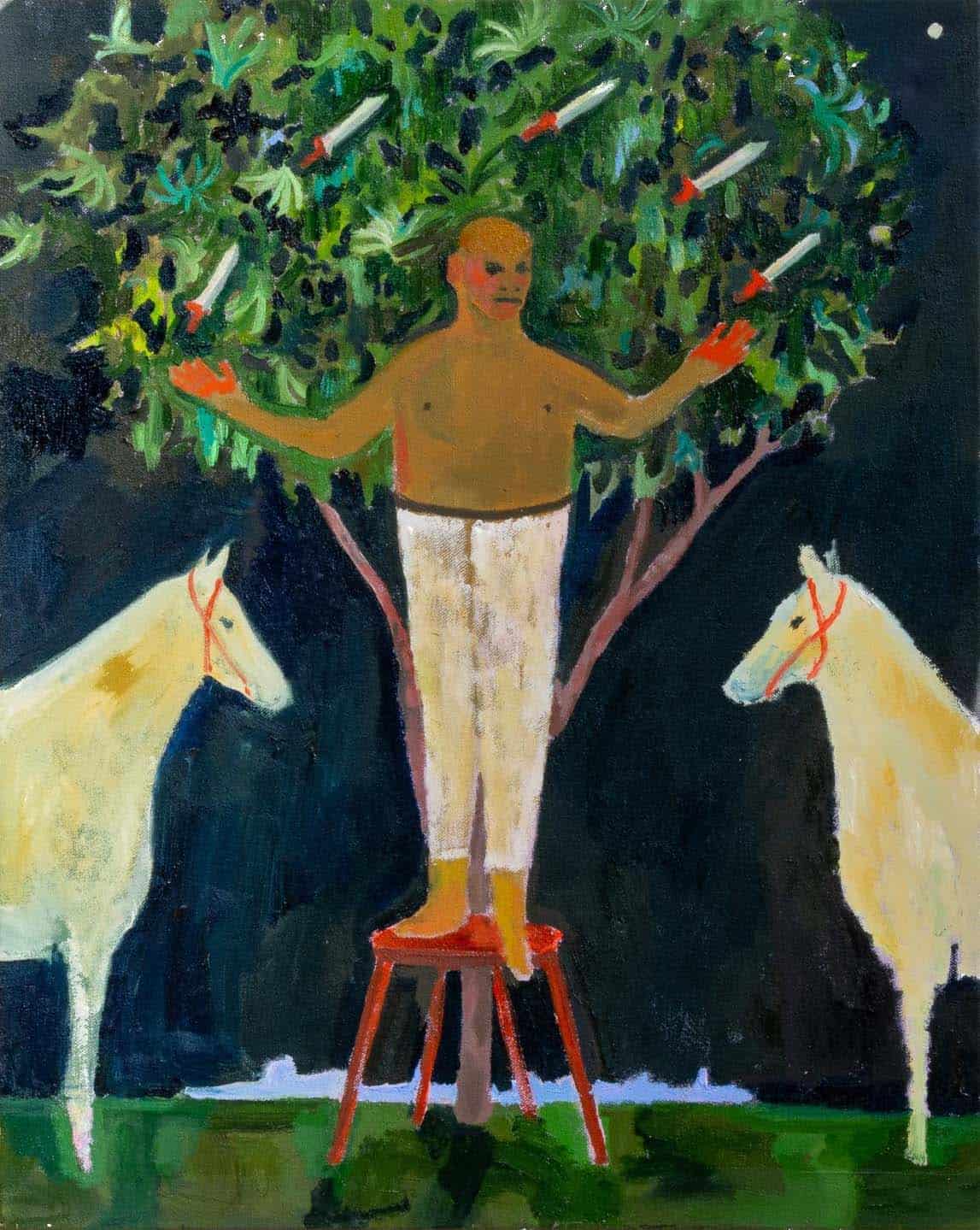

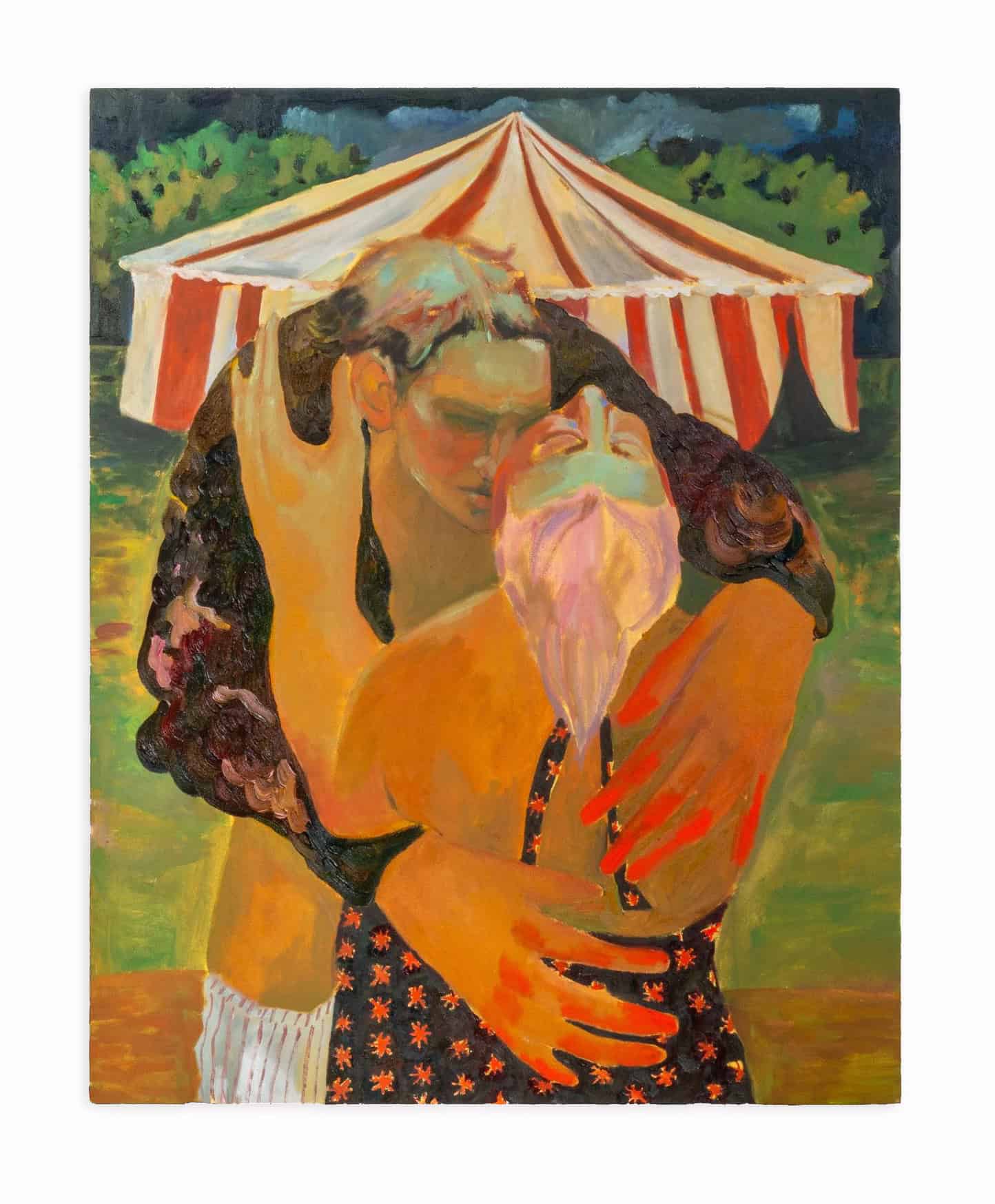

Throughout these paintings, witches old and new, smoke cigarettes while accompanied by animals that move from frame to frame, from light to dark, from dreams to reality, to enchantment. Men and woman share spaces of illusion and desire, navigating the ambiguous ground between magic and trickery. Sex appears as a driving force, as does love; in one painting a man juggles with knives, while in another someone levitates between trees. The red hands of Torres’ imagined characters communicate from picture to picture, as if carrying hot messages between them, sometimes transformed into red stars.

As a young woman painter from the Colombian Caribbean, Torres is faced with the problem of constructing an identity, whilst simultaneously countering a constant exoticization from the outside gaze, and the dominant narrative’s desire to encapsulate her work, and even her existence, in racialized and colonized terms. Rather than being complacent of these expectations, she works through the particular affects of creole identities and cultures within a context of globalization. Torres’ work is not confrontational, rather it seeks to search for new ways of being in the world, questioning Eurocentric views placed upon Caribbean culture, and manufacturing a renewed agency of painted signs. Through the act of painting, Torres embodies a search for the representation of a personal symbolic universe, conjuring animals and humans alike to embroider a web of meaning.

El Animal de la noche era lo que quedaba de nuestro deseo (The animal of the night is what was left of our desire), 2024. Lorena Torres: El Milagro es la Pereza de Díos

Legends of transmutations and the miracles that occur under the equatorial sunshine are fertile ground from which Torres extracts and remixes secret codes in order to encounter new meanings and representations of female agency in a culture that has been predominantly machista (sexist). On the banks of the Magdalena River, a tale transmitted through Caribbean oral culture tells the story of the Hombre Caimán [the Caiman Man], a lascivious male whom, with the help of a magical potion brewed by a sorcerer, sought to become a caiman to spy on the women who came to bathe in the river. Two of the paintings in the exhibition reclaim this narrative, placing a woman in the space of the man, as a means of negating the male gaze. In La mirada de Dios o el milagro es la pereza de Dios (The look of God or the miracle is the idleness of God), ‘los ojos de Dios’ [the eyes of God] overlook this woman caiman, bathing her with a benevolent, calming, and warm light. Even the eyes of God are overstatedly feminized, as to emphasise that it is through a woman’s eyes that Torres’s pictorial mythology is constructed.

Doves, dogs, horses, caimans and snails; purple, yellow and white flowers, move between the characters of Torres’ paintings, as if they were helpers in the conjuring of the spell of what Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier named “Lo real maravilloso americano” [The marvelous real in America]. Torres’ new body of work, in which she creates symbolic landscapes and moments, is not only a revision of this search for the identity of the Caribbean creative ethos from a feminine standpoint, but also a reminder of our collective need for reclaiming space for the ritualistic and esoteric experience in everyday life

(By María Adelaida Samper)