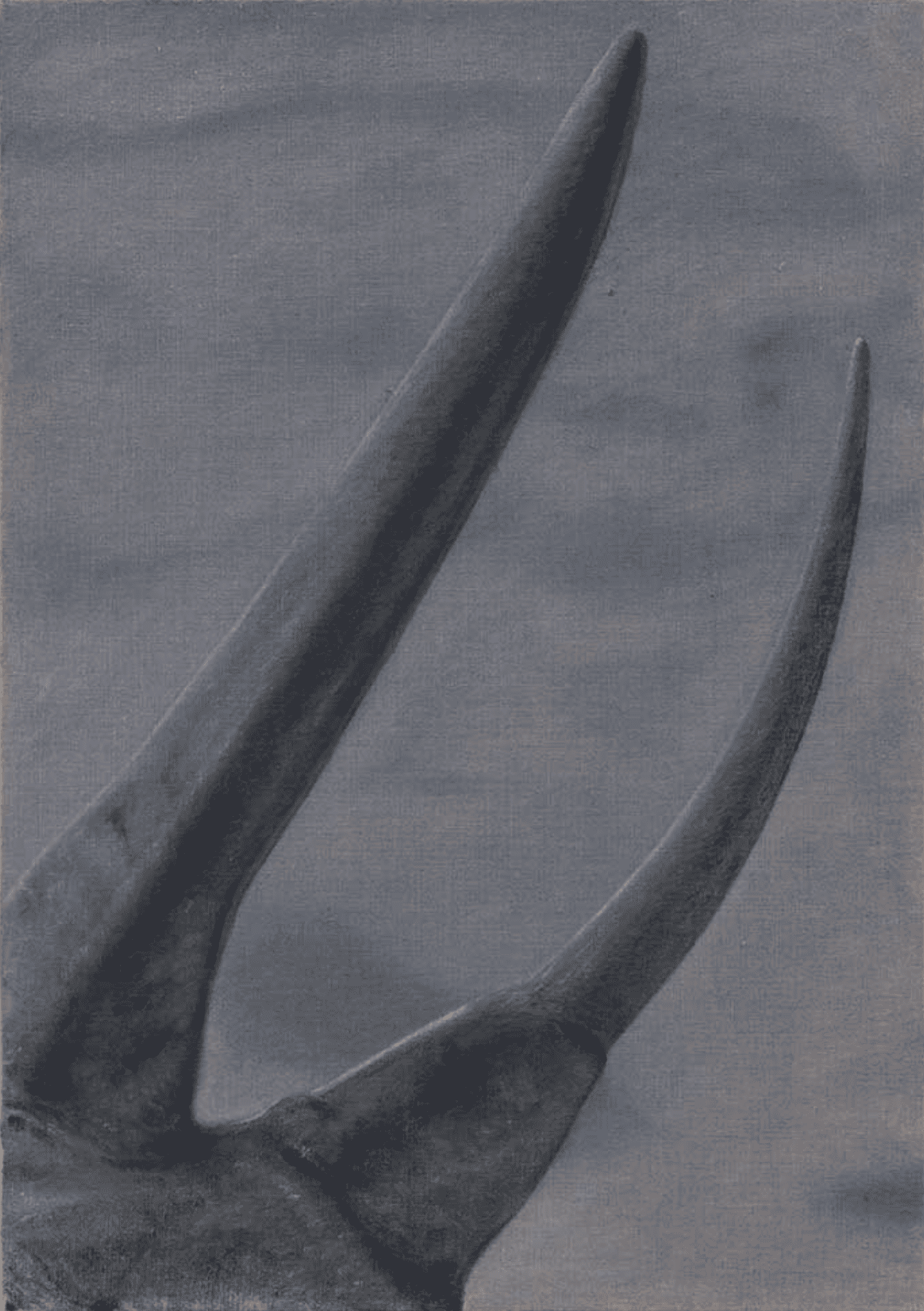

Faux, 2023

There’s a chapter of Peter S. Beagle’s novel ‘The Last Unicorn’ where the unicorn is captured by a traveling carnival, joining a parade of caged animals masquerading as mythical creatures, though their fantastical appearances are nothing more than illusions conjured by the carnival’s witch. This deceitful magic is dismissed by the resident magician:

“Her shabby skill lies in disguise. And even that knack would be beyond her, if it weren’t for the eagerness of those gulls, those marks, to believe whatever comes easiest.” (p.23)

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live” Joan Didion famously begins – but those stories, however fantastical, run the risk of reduction, of pinning and hemming and clipping what we see before us until it’s only a crude outline of its true self. Complexity and contradiction discarded in favour of whatever comes easiest. The magician continues, lamenting that pre-packaged imitation is more readily accepted than the real thing:

“She can’t turn cream into butter, but she can give a lion a semblance of a manticore to eyes that want to see a manticore there – eyes that would take a real manticore for a lion, a dragon for a lizard, and the Midgard Serpent for an earthquake. And a unicorn for a white mare.” (p.23)

The people of Beagle’s novel have lost the ability to recognise a unicorn, seeing just an ordinary white horse in its place, and wouldn’t know one stood before them if it wasn’t for the same illusory magic that disguises the animals. The witch explains:

“Do you really think those gogglers knew you for yourself without any help from me? No, I had to give you an aspect they could understand, and a horn they could see. These days it takes a cheap carnival witch to make folks recognise a real unicorn.” (p.32)

Watching the film as a child, more than the imprisonment or spectatorship, it was this simple mirage that made me feel that something terrible is happening. It resonates with the pain of every misjudgement, every clipping and hemming, every indecent pantomime suffered under the promise of inciting even the faintest hint of recognition. All against the fittingly camp backdrop of childhood fairy tale, it balances this subtle grief with the juvenile expression of the emotion it elicits, the kind of petulance that can only be induced by the deepest wounds – and now, for me, there isn’t an instance of misunderstanding that isn’t accompanied by Mia Farrow’s indignant “A horse? A HORSE am I?!”

These metaphors are our modern mythology, how we make sense of the world. We no longer take a lion for a manticore, but we might post a picture of a cat with the caption “it me”. This could be taken as its own kind of violence on the things around us, on any subject with the misfortune of being swept up in our own carnival, or, more generously, it acknowledges how each narrative can bend and skew another, and equally be shaped in return – that, as Beagle writes, “all things are crouched in eagerness to become something else”. Our myths and memes act as outfits – we dress up our surroundings in our own image, and wear them as a disguise in the hope of finally being seen. “The universe lies to our senses,” Beagle continues, “and they lie to us, and how can we ourselves be anything but liars.” – and yet Beagle’s story also rings with a joy that balances the sorrow of misrepresentation: how good it feels to be seen, by someone who knows what they’re looking at

(By Grace Lee)