Genesis Baez, Lifting Water, 2017

I belong to this brings seventeen artists together around themes of self and family, private rites and communal ritual, along a continuum of becoming. The title of the show is from Ariana Reines’s poem “Save the World”, and can be read as a declaration of identification, a promise of solidarity, or a blurring of self into multitudes.1 These artists mark an intractable this. The camera points, more like an ear than an index finger, in the direction of what is felt rather than seen and to those invisible threads that hold us together. Keisha Scarville camouflages her body in her late mother’s clothing, embraced in the fabric and levitated by it. Over her mother’s matrimonial photograph, Cheryl Mukherji embroiders her mother’s words, “Promise me you will not become like me.” For these artists, as with Genesis Báez, the symbiotic connections to the mother’s body and to the motherland are the first condition of photography. In Lifting Water, 2017, a large glass cylinder of water balances precariously between Báez and her mother: the ocean between Puerto Rico and New York. Sydney Mieko King reverses time; plaster casts of her body are projected onto archival photographs of her maternal grandmother. The projection rests, ghostlike, on an intermediary glass pane, invisible except for a star of masking tape to prevent the pane from shattering. Depictions of violence and religiosity sit in uneasy proximity in Calafia Sanchez-Touzé’s allegorical tableaux of her family. Sanchez-Touzé pictures her mother prostrate across a bed, genuflecting in a posture of grief or mourning.

Annie Wang’s twenty-year project gradually builds portraits of herself and her son in front of the previous year’s photograph, creating a palimpsest of the mother-and-son family portrait. Qiana Mestrich’s son bows his head low in concentration as his arms take flight in dance; a grid of photographs maps his movements across time and space. Gwen Smith’s collages merge painting and photography. In one, a drawing of Tamara Lanier— the woman suing Harvard University for the return of daguerreotypes of her enslaved great-great-great grandfather and his daughter—partially covers an archival photograph of herself with her siblings. Smith’s family album reaffirms the line of Lanier’s ancestry that has been institutionally erased.

Diana Palermo writes incantations with light—half poem, half spell—chemically rendering her gestures into language. In Jacky Marshall’s collages, drawings of naked women are transformed into photographs. Both Palermo and Marshall mediate longing by translating it into tactile objects. Shala Miller’s silkscreen Play, 2020, roots history and language in her body. Like song, Miller’s work rises up, transforming psychic pain into something visceral and resonant.

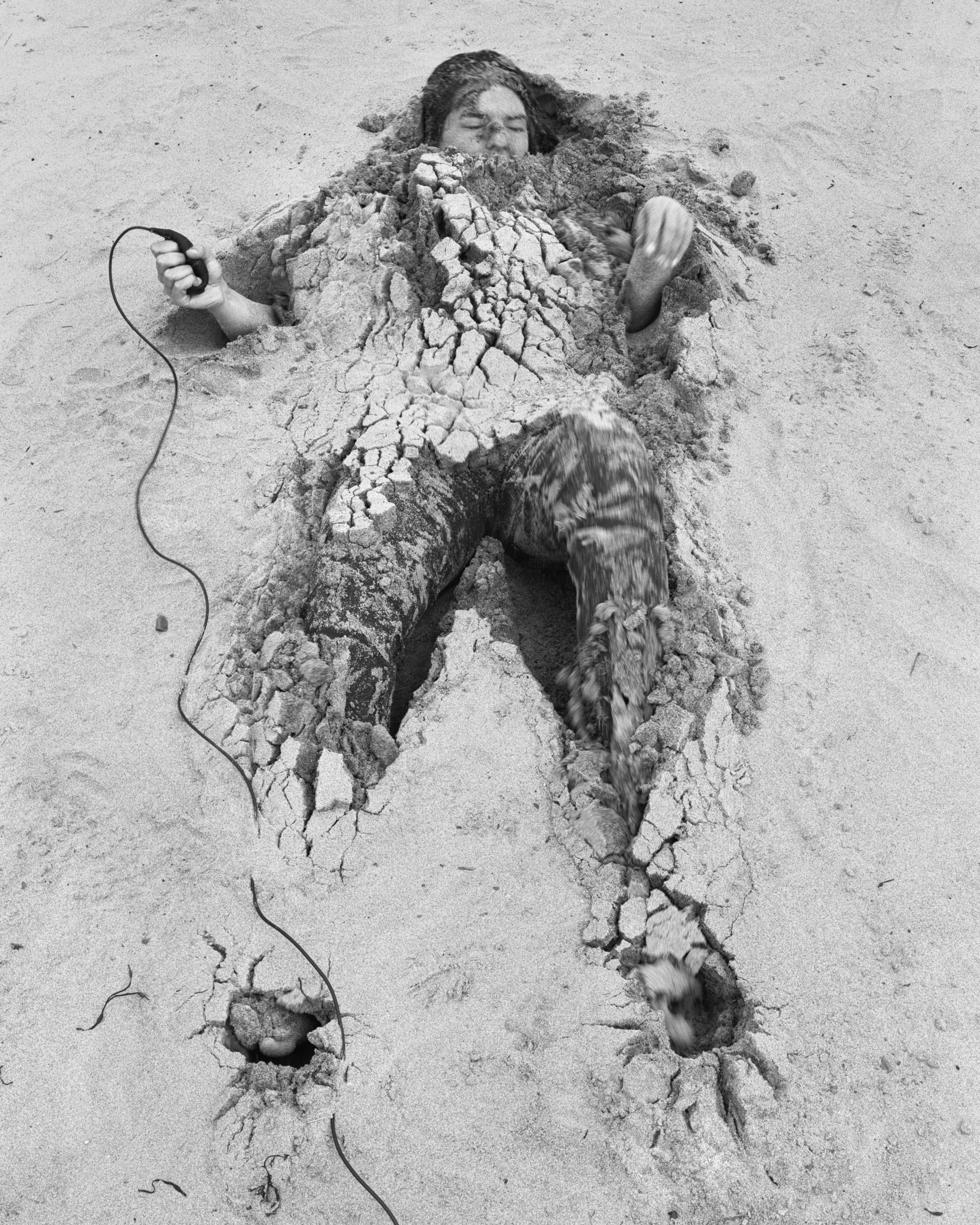

The Jewish prayer Anne Vetter sings in Avinu Malkeinu, 2020, pleads with God for mercy. Vetter’s voice folds in on itself in the two-channel video, alternately harmonious and discordant. Birds signal the minor transcendences of everyday life in Wendy Small’s work. A.K. Jenkins masks themselves behind their maternal grandmother’s Church fans in a playful series of self-portraits. Their performance embodies institutional belonging and its erasure of personhood. Jenny Calivas performs her own burial in silver gelatin prints: a hand bursts from the ground in triumphant possession of the cable release, fissures form around the body, ejaculatory sand spills between open legs.

Naima Green photographed her queer community for Pur·suit, 2019, and printed them as playing cards, a continuation and expansion of Cathy Opie’s Dyke Deck. The cards are part of a larger digital archive preserving narratives of queer identity. Keli Safia Maksud’s sound piece recovers the hymnal undercurrent of the Algerian national anthem. She converts a war song, aurally connecting listeners in opposition to postcolonial nationalistic ideals.

I recall a line in another Ariana Reines poem, “Coeur de lion”, about a tattered flag in a puddle.2 I like to hold that image in mind when presenting these artists, because they consistently refuse an emblematic or fixed identity. Instead, they have squeezed, smeared, and repurposed their DNA into a family album without limit, resurrected ancestors, and activated psychic space in order to give shape to their experience. Photography, here, works in resistance to harmful power dynamics by creating new rhizomatic pathways to knowledge in a pact between camera operator, subject, and viewer. These acts allow us to recognise ourselves through and among others.

Gwen Smith, Exquisite Family Album – Sister Sledge X Stage Coach Mary, Whipped Peter (Gordon) and My First Passport Picture, 2021

(By Justine Kurland)