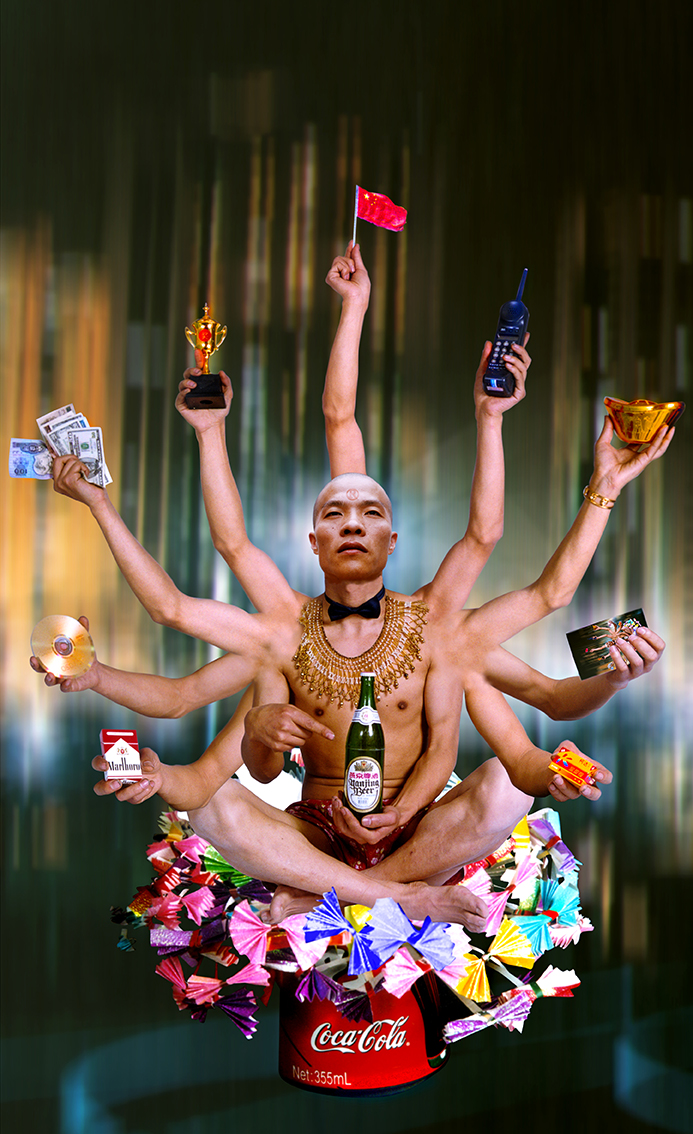

Taken cumulatively, Wang Qingsong’s images carry a wry corrective to global capitalism, consumerist values and the corrosive infiltration of western aspirations into Chinese culture.

Martin Barnes

Wang Qingsong’s photographs are an immediately impressive visual spectacle. They are often epic in their physical scale (regularly over three meters long), dazzling or gaudy in their colour palette, dynamic and emphatic in their composition and hugely ambitious in their production values. Behind many of the photographs lies an entire team of people working in a studio environment that is more like a theatre production or film set than a regular photographic shoot. There are models, props, special effects, and incredible feats of staging, all working together in preparation for the final photograph.

In addition to their technical and visual allure, Wang Qingsong’s images convey pressing social narratives and display his sardonic and critical intelligence. The mind behind the images is always evident: it is enquiring, playful, emphatic and satirical. His photographs co-opt the impact and visual vocabulary of western big-budget advertising – as well as propaganda images of the Chinese Communist regime’s Cultural Revolution – and uses them against themselves. At the same time, they channel the heritage of ancient Chinese arts such as scroll painting, as well as references to European old master paintings, and thereby meld both east and west, past and present.

Born in 1964 in northeastern China, he grew up in an area of oilfield towns where his parents were employed. After his father’s death in an oilfield accident, the teenage Wang Qingsong took his father’s place to help provide for his family. During the eight years that he worked on the oil-drilling platform, he also took part-time art classes and applied for China’s art academies. After much perseverance, he was finally admitted to study painting at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts in Chongqing. The artist moved with fortuitous timing to Beijing – the center of cutting-edge activity – in 1993, where he at first continued painting, but then transitioned to photography, and has lived and worked since. As a result of his location in time and place coupled with his visual flair and ability for incisive social critique of his era, he has emerged as a central figure from the epicenter of a remarkable revolution in Chinese photography.

Though they can be enjoyed in isolation, it is useful to consider Wang Qingsong’s photographs within wider historical contexts. The artist has emerged and endured as one of the most prominent among a group of Chinese lens-based practitioners whose work exploded onto the international scene from the middle of the 1990s. What was it that led up to and engendered such an outpouring of vibrant artworks, especially photographs, from China at this time?

After years officially serving the purposes of political propaganda within the People’s Republic of China during the mid twentieth century, photographers slowly gained new freedoms of personal expression. This followed the initiation of the Central Government’s ‘Open Door Policy’ in 1978 that opened China up to the outside world and established Special Economic Zones, where market forces could be tested. In 1989, the first nationwide avant-garde art exhibition opened at the National Gallery in Beijing. However, that same year, burgeoning freedoms were halted and called into question when demonstrations against inflation and government corruption led to mass protest and violent clashes in Tiananmen Square. Official prohibition of avant-garde art followed. Artists were compelled to evaluate and address the contradictions between freedoms and oppression alongside their shifting cultural identities.

After reforming debates within the Communist Party, Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping reaffirmed the Open Door Policy and Special Economic Zones in 1992, which kick-started the country’s economic boom. As a result, international commercial galleries and art-school affiliated spaces first emerged in Beijing and Shanghai and artists started to gather in Beijing’s East Village.

Performance artists and photographers worked together to create pieces and establish magazines that circumvented state censorship and police interference. Years of curtailed personal expression was let loose and was coupled with sudden unprecedented freedoms. This produced highly individual artistic responses with a politicized sense of directness and urgency in their expression. Many artists became subversive and used kitsch and satire as devices of critique. The term ‘gaudy’ was coined for the maverick art practices of this time and Wang Qingsong became associated with this movement.

The exhibition of works by twenty artists from China at the 48th Venice Biennale in 1999 put Chinese contemporary art firmly on the international map; and in 2003 the exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, Alors, la Chine?, became the first international exhibition of experimental Chinese art to be formally sponsored by the Chinese government. This signal of increased official acceptance showed China’s recognition of the value of its cultural export. Opening up the country resulted in the bewildering paradox of seductive Western capitalist exports (global brands, advertising, its associated glamour and affluence), combined with local, centuries-old traditions and the powerful shadow of the Communist regime. Wang Qingsong’s work emerged within this ferment, reflecting back its contradictions and consequences.

Many of the most inventive and younger artists in China chose to work with photography and video because of the versatility and instantaneous nature of these media that mirrored the rapidity of change in the country. (An extension of this today can be seen in the recent emergence of ‘microfilms’, or ‘Wei Dian Ying’ – low budget amateur digital movies hosted on streaming websites such as YouTube and Youku). In contrast with the west, fine art photography in China has not been weighted to the same extent with a canonical history and precedents: the connections and parallels with Impressionism, Modernism, Postmodernism and other art movements, and the intertwining of photojournalism, ‘personal work’ and commercial practice in fashion photography or magazine editorial. It does not have the same reliance on the cult of the fine black and white print to signal serious or poetic intent. Instead, in the mid-1990s, exciting developments in the fields of appropriation from advertising and propaganda, alongside performance-oriented body art, became a driving force. Many artists gathered in Beijing and had come, like Wang Qingsong, from the provinces. They moved to Beijing’s run-down districts for its cheap housing and then found inspiration in their decrepit surroundings. In the East Village, this led to a series of groundbreaking, collaborative art projects, with photographers and performance artists acting as each other’s models and audiences. These projects had a profound impact on Chinese art of the next decade. Large colour photographs documenting ephemeral body art performances emerged or constructing realities based on daily life as a distinctive practice. It is against this backdrop that Wang Qingsong’s work can be better understood.

I first came across Wang Qingsong’s work in 2005 when it was included as part of a touring exhibition, with an accompanying book of the same title, that now stands as a landmark in the field: Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China. The exhibition was the first comprehensive and interpretive survey of its type, devised between curators at the University of Chicago and the International Center for Photography in New York, and adapted for the showing in London at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A). It highlighted the scope and vividness of contemporary photography that had emerged from China in the decades following its remarkable economic, social and cultural transformation. Even in its reduced form, the V&A version of the exhibition featured eighty works by forty artists who reflected the energy of younger Chinese artists at the start of the 21st century. Many of the works combined optimism and excitement with a sense of anxiety at the breathless pace of change. Like Wang Qingsong’s works, many pieces in the exhibition were monumental in scale, experimental and conceptual in nature. The exhibition was divided into themes that gave a flavour of the artists’ prevailing concerns, many of which resonate for Wang Qingsong: ‘History and Memory’; ‘Re-imagining the Body’; ‘People and Place’; and ‘Performing the Self’. At the time of the exhibition, Wang Qingsong visited the V&A to attend the opening, but also to view the nineteenth-century staged photographs in the permanent collections in the museum’s Prints & Drawings Study Room. (His break-through photograph, Night Revels of Lao Li, 2000, joined them when it was later acquired by the museum). Staged photography reaches back to the invention of the medium, and flourished up until around the late 1860s.

This phenomenon can be explained through a combination of factors: technical requirements of long exposures with early negatives that could not capture movement in action; the Victorian penchant for amateur dramatics and narrative tableaux vivants; and the need for photographs to imitate the compositions of paintings to gain validity as a fine art. Exposure times increased, and photography gained its own validity distinct from painting in the snapshot aesthetic, so tableaux photography declined. Aside from within fashion, staged photography fell out of favour for nearly one hundred years, but was revived in Europe and North America from the 1970s as a device used deliberately in conceptual and performance art. It also served postmodern ideas that called attention to the artifice of photography, revealing its visual methods, construction and ideologies.

As we have seen, in China, staged photography arose predominantly out of video and performance art alongside a familiarity with the grand productions of Communist propaganda imagery. Yet it also chimed with similar approaches, albeit derived from differing impulses and sources, in the west. (Wang Qingsong’s work has sometimes therefore been compared to North American contemporary artists such as Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall or Gregory Crewdson). As a result, Chinese staged photography, with Wang Qingsong at its forefront, arrived in the late 1990s to a receptive western audience and an art market that recognized its visual codes but delighted in its difference.

Dream Of Migrants, 2005

The 2015 exhibition at Huxley-Parlour Gallery brought together a retrospective selection of works spanning Wang Qingsong’s career. It encapsulates the range of his most important themes: the legacy and survival of ancient art and culture in present day China (Requesting Buddha No. 1, 1999; Red Peony, White Peony and Frosted Peony, 2003; Temple, 2012); the impact of the recent opening up of the country to the economic forces of the West (China Mansion, 2003; Romantique, 2003; One World, One Dream, 2014); and the tension resulting from the influx of migrant workers in China’s cities (Dream of Migrants, 2005; Home, 2005). The artist amply describes and explains in his own words the meanings behind the individual works in the texts that accompany the reproductions in this book.

Taken cumulatively, Wang Qingsong’s images carry a wry corrective to global capitalism, consumerist values and the corrosive infiltration of western aspirations into Chinese culture. As one writer has noted: “His work is both a kind of metaphor and the expression of a predicament at the same time”. Devastatingly effective in their critique, his images are imbued with the acute quality of reverse propaganda. He shuttles between satire and what he describes as ‘photojournalism’ – but not in the traditional sense. As he has noted: “I’ve always thought of my work as press shots, not some kind of conceptual photography. You can read into press photographs. I hope that people understand my work like learning to read with pictures”. He is a reporter-artist, a kind of jester or wise fool, who taps into the essence of topical issues through strategies of exaggeration and dark humour, through the imaginative rather than the specific. He does this in a manner that reminds me of the acerbic and humorous eighteenth-century British satirist artists, Thomas Rowlandson or William Hogarth. Wang Qingsong has a similar facility with his cast of characters. They often appear like models in dioramas, and the artist himself can sometimes be seen as a protagonist looking on, or performing within, his own images. Wang Qingsong positions himself therefore simultaneously as a maker, manipulator, performer and an astute observer.

Over the last twenty years, experimental artists have consistently responded to the drastic changes taking place in China: large-scale internal migration, the disappearance of traditional landscapes and lifestyles, the rise of mega-cities, the indulgence of consumer fantasies, a widening distance between rich and poor, and new urban cultures. Many of their works reflect a growing awareness of the fragility and mutability of China’s urban fabric. In the past two decades, China’s urban life has been completely transformed. Sprawling skyscraper cities have been created almost overnight, while historic urban centres have been utterly demolished, displacing tens of thousands of city dwellers. Although demolition and relocation were necessary to the much-needed urban modernization, the resulting social structure and its accompanying consumer culture have arguably brought about a growing alienation between the city and its residents. Wang Qingsong is one of the most powerful commentators on this recent situation in China. However, his work has a wider reach – beyond the topical specifics of this time and place. It points out the age-old human contradictions between the material and the spiritual. It is true that isolation, greed, waste, excess, despair and folly are often Wang Qingsong’s themes. Yet the fact that he transforms them into art, and they are brought to our consciousness, means that he tackles them with hope

(By Martin Barnes)