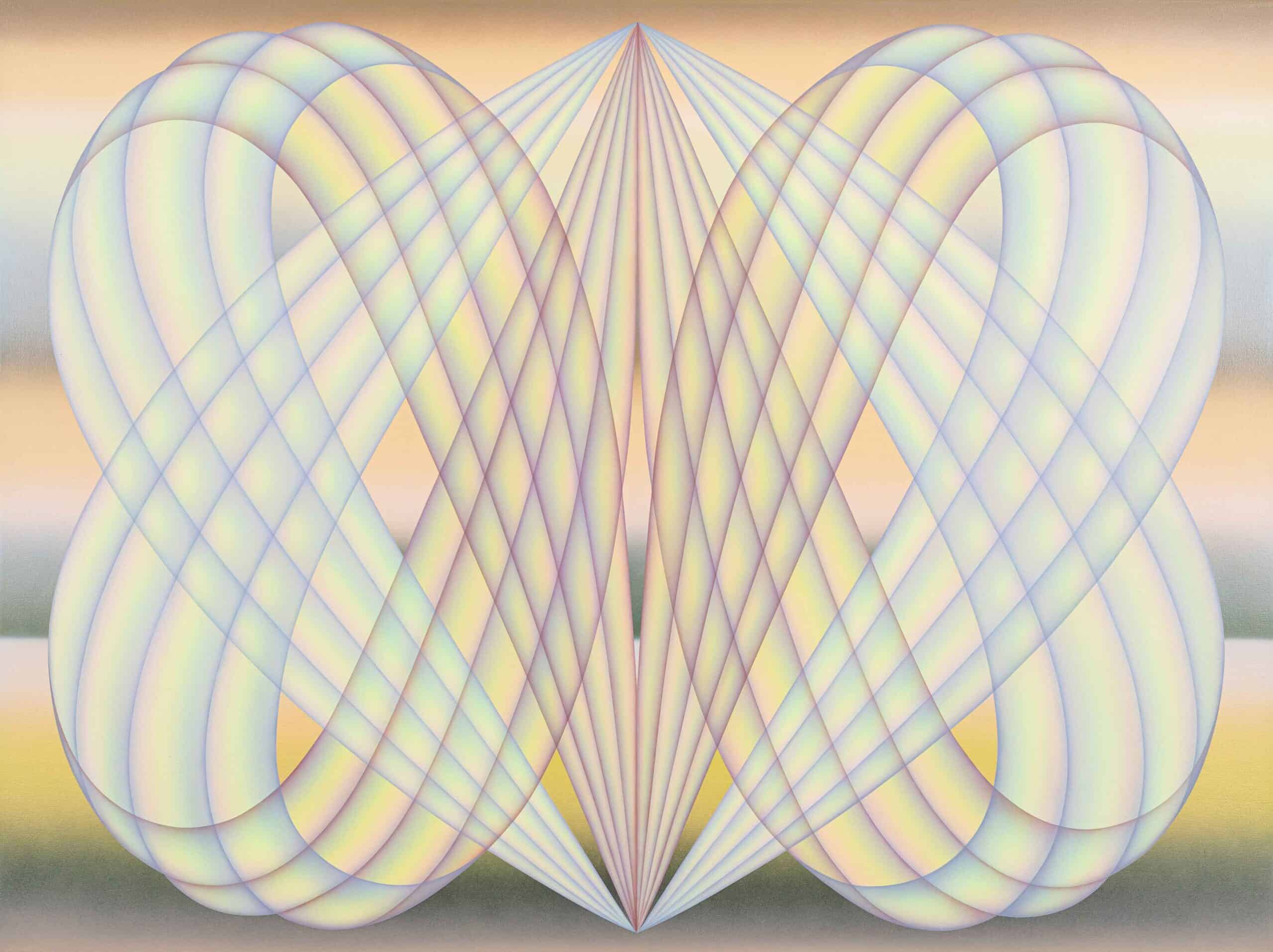

Pelt, 2024

This text was commissioned on the occasion of Molly Greene’s 2024 solo exhibition, Pseudopodia. The text is written by Ella Slater, a London-based writer. She has published work in émergent magazine, Frieze, Intra Venus and Elephant magazine.

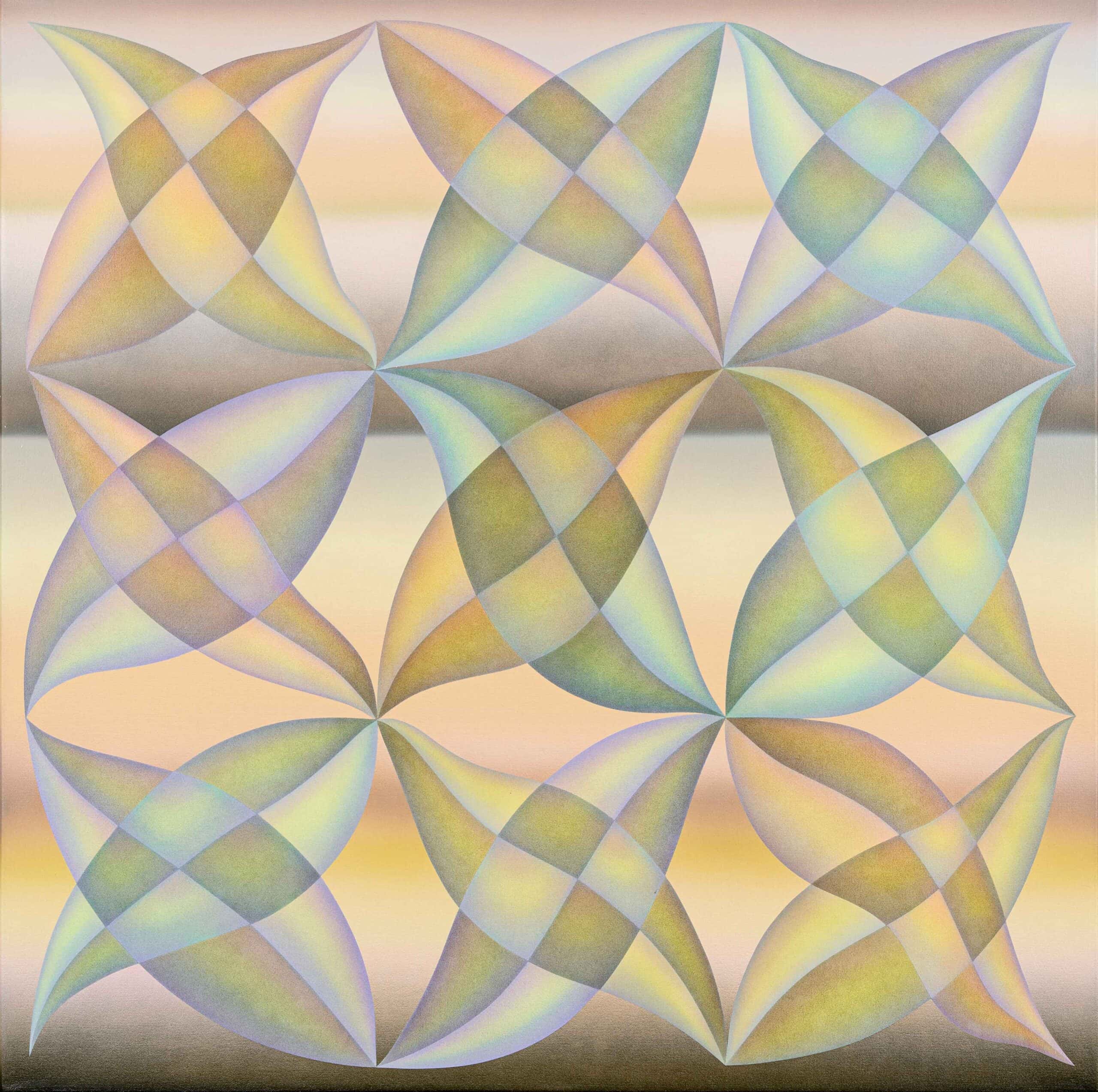

It is difficult to capture the paintings of Los Angeles- based artist Molly Greene in words, since their subject is the representation of that which eludes language. They are – explained in the simplest manner – reflections of the amorphous nature of existence, as manifested in the corporeal. In this sense, they are somatic visualisations, calling to mind the words of the poet CAConrad: “(Soma)tics [are] ritualised structures where being anything but present [is] next to impossible”. The ‘present’ – or being present – of which Conrad writes is otherwise known as cellular consciousness; the ultimate embodiment (awareness) of the self. Greene’s works may seem otherworldly in their style, which recalls the practices of Hilma af Klimt, Agnes Pelton and Florence Miller Pierce, but they are, in fact, the opposite: deeply, and entirely, concerned with the inhabitation of a body.

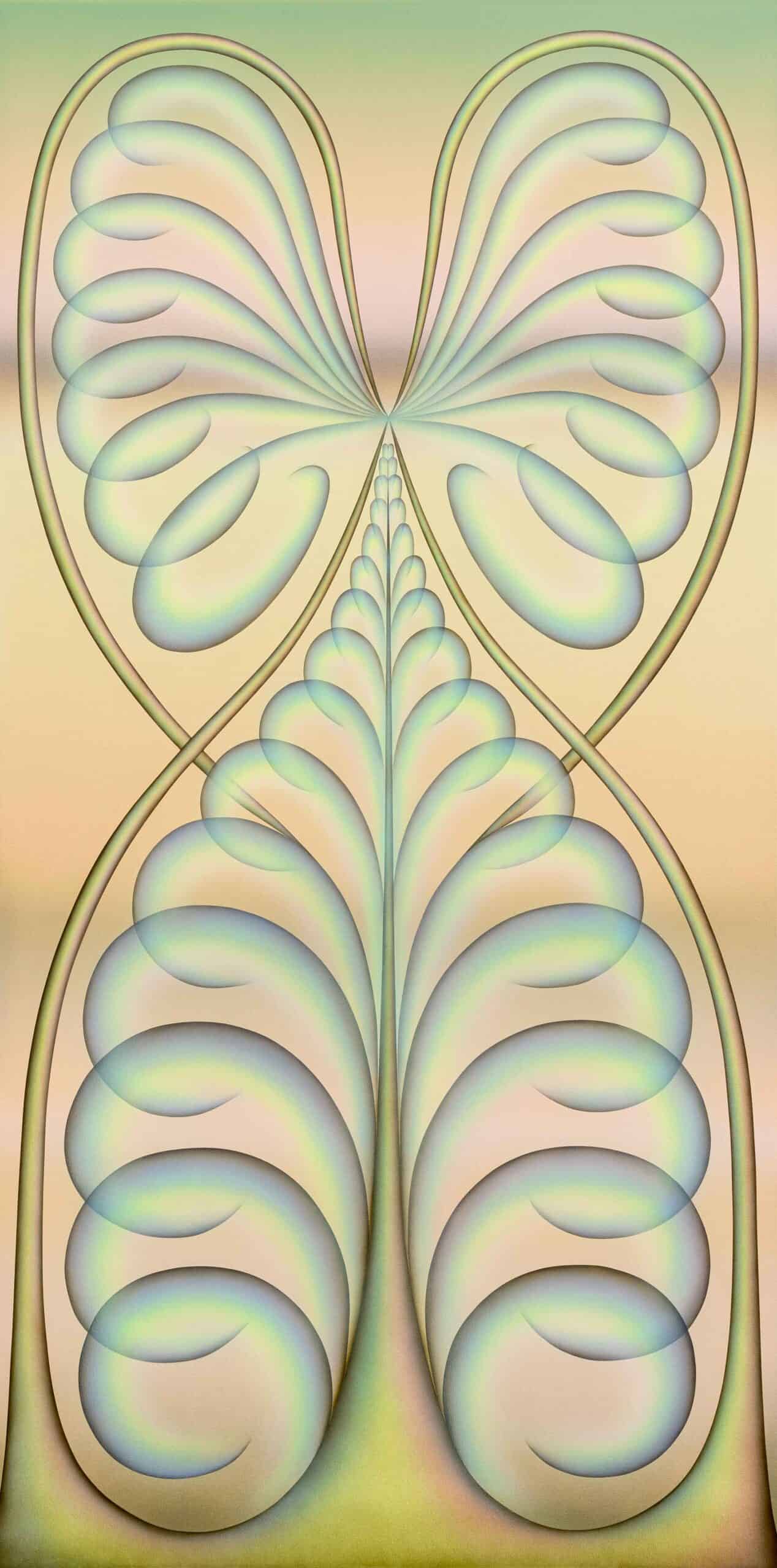

A while ago I visited a workshop based on Conrad’s (soma)tic teachings. To achieve the aforementioned cellular consciousness, participants were asked to induce a kind of intentional Alice in Wonderland syndrome: the burrowing into the body (the complete awareness of it), until we became totally within ourselves. I concentrated hard on the images behind my eyes, which were of a similar prismatic colour palette to that of Greene’s paintings. The artist, however, offers a more accessible pathway to embodiment. Her canvases are portals themselves; though nebulous in form, they are focused in their illustration of the body’s porous nature. In them, patterns seem at once organic, metaphysical and digital. The cell (the micro) is made macro; even the show’s title, ‘Pseudopodia’ – the process by which amoebas grow, and then reabsorb, arm-like protrusions to move – nods to the interconnected, nebulous morphology of the body and the world surrounding it.

Parachute, 2024

Greene’s dramatic abstractions also give form to the non-physical, although they are tied neither to organised religion or esotericism. The body and its inextricability from earthly forces, the artist tells us, does not negate a concern for metaphysics. Her canvases are meccas of interrelated energy; crystals devoid of their New Age associations. I am struck by a series of indistinct, hazy lines which punctuate the backgrounds of various works, sometimes concurrently in groups. They appear as shimmering horizons: blurred boundaries between land and sky; self and other. For Greene, the external lives on the same plane as the bodily. Though her practice has an aesthetic relationship with that of the Transcendental Painting Group (which included the aforementioned Pelton and Pierce), her existential investigations are less rooted primarily in the unconscious and more in Conrad’s ‘present’, where “the many facets of what is around me, wherever I am, come together through a sharper lens… (soma)tics reveal the creative viability of everything.”

One of Greene’s enduring references is Mel Y. Chen, whose book Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (2012) argues that ‘animacy’ (the quality in a noun which alludes to something animate, or alive), underlines much of contemporary culture, from disability theory to animal rights. In particular, it highlights the interruption of distinction between human and ‘non-human’; one example being of the metals which exist, naturally and artificially, within our physical forms, another being the ‘animalisation’ of certain humans throughout history, and its consequent effects on immigrant, racial and sexual minorities. Chen’s work is a concrete example of the ways in which the distinctions we draw affect us on various levels: in our attitudes towards others, as well as our own physical existence. Back to ‘pseudopodia’, which then becomes a metaphor for the fluxes of boundaries within bodies, as well as the relationships between them. As Chen, and subsequently Greene, argue, consideration for the corporeal – somatics – invalidates the isolation of the body. Like the patterns which multiply and spread over Greene’s canvases, our existence is a process of inosculation, intwined with and affected by everything around us. In turn, we are no more powerful or deserving than anyone – or anything – else.

As nouns (‘animacies’) fail to reflect the blurriness of life and matter (human and non-human), Greene’s art evokes what eludes linguistics, instead working towards its own language of abstraction. It is a language befitting of our materially abstracted, unsettled world. It points towards something larger and interconnected; something beyond the individual, but entirely grounded in existence. No longer can we afford the rampant anthropocentrism which has, throughout history, oppressed ‘the other’: other animals, other humans; the Earth itself. As Greene demonstrates, through re-understanding the body’s physicality as entangled with, rather than refuted by, external (social, political and ecological) symptoms, we become Conrad’s ‘present’; wholly aware of our true place in the world

(By Ella Slater)