An Ideal for Living: Photographing Class, Culture and Identity in Modern Britain

27.7 – 17.9.2016

Includes:BillinghamBrandtBulmerCartier-BressonDavidsonDenchDepardonErwittFoxHabichtHoppéHussainJonesJones-GriffithsKillipLibbertMorrisParrJonesPhillipsSheltonRidgersSchadebergSpence–

Closed

Hours

Monday to Saturday, 10:00am – 5:30pm

Gallery

3–5 Swallow St

London

W1B 4DE

An Ideal for Living is an exhibition about how photographers have perceived class, culture and identity in modern Britain. Drawing on the work of 29 diverse photographers, it considers how photographing Britain has contributed to the creation of a collective national identity. The exhibition shows the variety and creativity with which photographers have sought to document what they consider to be a particularly British way of life from the 1920s to now.

Includes: Richard Billingham, Bill Brandt, John Bulmer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, Peter Dench, Raymond Depardon, Elliott Erwitt, Anna Fox, Frank Habicht, E. O. Hoppé, Mahtab Hussain, Colin Jones, Philip Jones-Griffiths, Chris Killip, Neil Libbert, James Morris, Marin Parr, Tony Ray Jones, Charlie Phillips, Syd Shelton, Derek Ridgers, Jürgen Schadeberg, Jo Spence

Syd Shelton. Civil Liberties Activist, Darkus Howe, Addresses ‘Anti-Anti Mugging March’ Demonstrators from the Roof of a Public Toilet, Clifton Rise, Lewisham, London, 13 August 1977

The exhibition opens with photographs of British life in the interwar period. Photographs by Emil Otto Hoppé, Bill Brandt and Henri Cartier-Bresson show the early preoccupation with documenting the British class system. Brandt’s landmark photobook, The English at Home (1936), cast a satirical look over social divides and notions of English propriety. The publication would go on to become a benchmark for photographers seeking to comment on the idiosyncrasies of the British class system as it has developed and subdivided through the course of the last century.

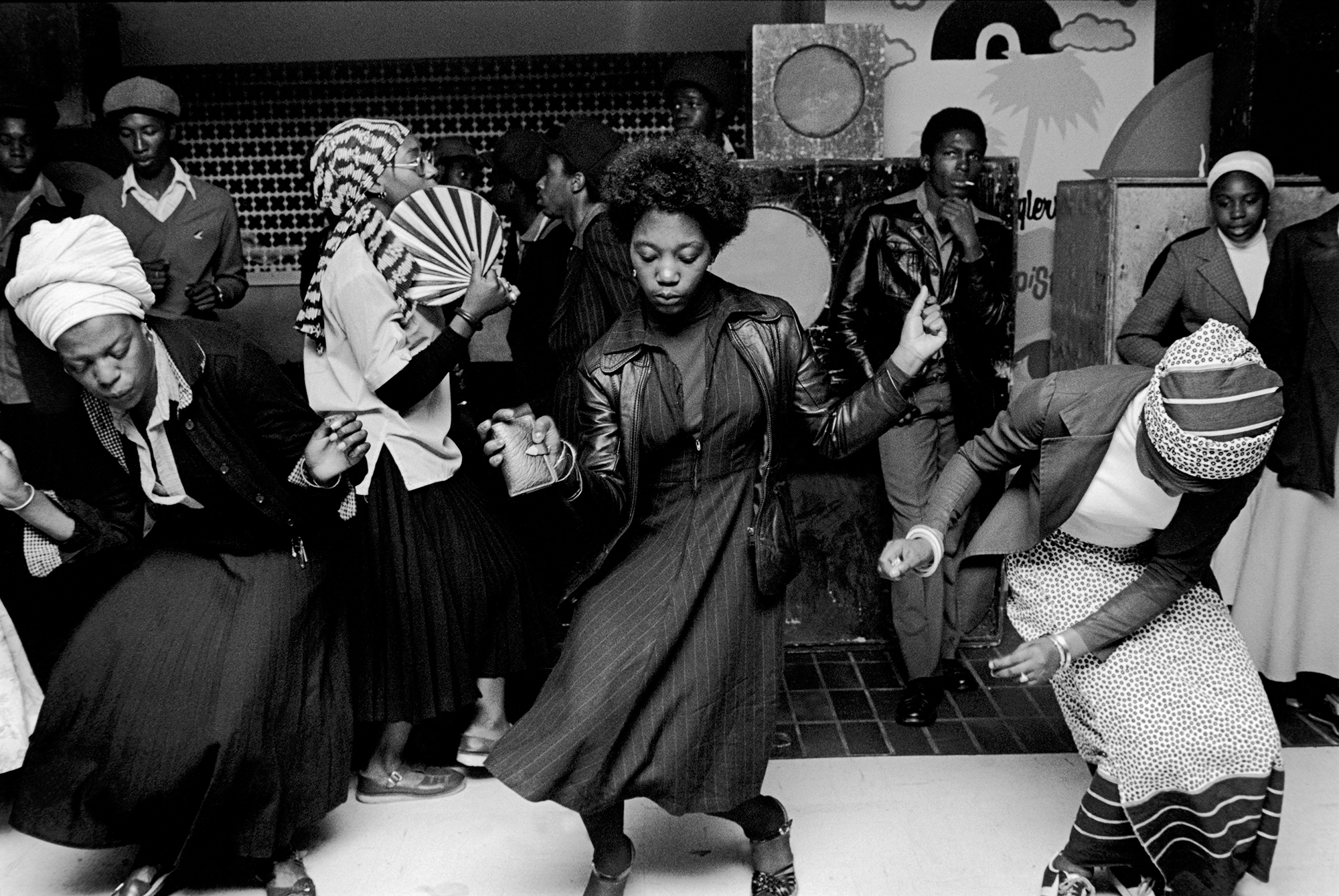

During the immediate post-war period, photographers including Bert Hardy and Thurston Hopkins took up the humanistic approach of Cartier-Bresson and early documentary photographers to focus on otherwise overlooked moments of daily life, as communities rebuilt in the wake of the Second World War. As the austerity of the 1950s gave way to the free-spirited libertarianism of the 60s, photographers like Frank Habicht sought to depict fashions, trends and political activism. Despite the egalitarian ethos embraced by the youth culture of the time, John Bulmer, Colin Jones and Bruce Davidson photographed the sharp delineations between classes with images of mining communities in the north of England and Wales. During the same period Charlie Phillips documented the integration of black communities into British towns and cities and Philip Jones Griffiths drew on his experience photographing the Vietnam War in his incisive reportage on the violence during the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

During the 1970s and early 80s, social documentary photography became increasingly important and many photographers addressed the consequences of the racist rhetoric espoused by political groups like the National Front. Syd Shelton’s photographs of the Battle of Lewisham in 1977 as well as Neil Libbert’s reportage on the 1981 Brixton riots documented racially motivated protest and violence.

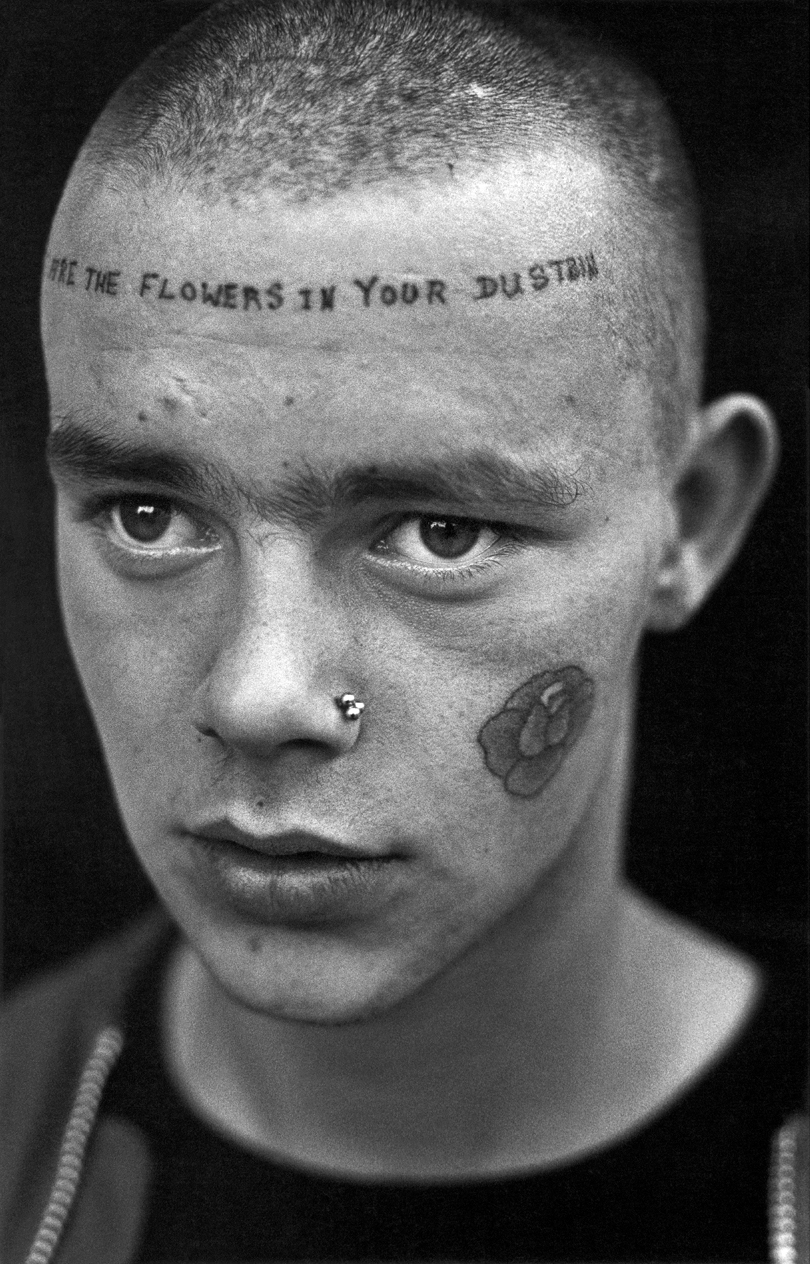

Photographers also continued to address the widening divide between classes as the heavy industries collapsed and working class communities were plunged into poverty during the years of Margaret Thatcher’s government. Chris Killip documented a community in Lynemouth that survived by collecting coal from the sea and Jo Spence depicted life on a gypsy encampment in Stratford. Raymond Depardon’s vivid images of deprived areas of Glasgow echo the tradition of post-war humanism whilst the role youth culture played in the creation of social identity in the 1980s can be seen in Derek Ridgers’ photographs of skinheads.

The fascination with the quirks and idiosyncrasies of British customs shown in Tony Ray-Jones’ photographs from the late 1960s would play a major role in the development of photographers like Martin Parr in the 1980s and 90s. The effects of tourism, consumerism and globalisation on British culture emerged in Parr’s highly influential series, The Last Resort, which documented the run-down seaside town of New Brighton on the Wirral. The interest amongst photographers in capturing the British during their leisure time would be continued in the work of Jürgen Schadeberg and Peter Dench. In the early 1990s, Richard Billingham turned his camera on his own family, documenting the trials of his alcoholic father in his seminal series, Ray’s a Laugh. The unflinching candour of Billingham’s portrayal of his own familial life spoke to wider issues within British society concerning drinking culture and social exclusion.

The social documentary photography of the 1980s and 90s has had a strong influence on contemporary depictions of British life, with photographers choosing to look at the socio-political issues that divide the nation. Anna Fox pioneered a style dubbed ‘subjective documentary’ in her photographs of the rituals of life in a rural English village, captured with an eye for the sinister and absurd. Elsewhere, the complex ties between national identity, religion and immigration have been portrayed in Mahtab Hussain’s work on Muslim communities in the UK. Environmentalism has also become a major concern in contemporary photography and photographers like Simon Roberts and James Morris have examined the role played by both the urban and rural landscape of Britain in the formation of national identity.

Highlights

9

Colin Jones. Untitled, Undated

Chris Killip. Helen and her Hula Hoop, Lynemouth Northumberland (1984)

Derek Ridgers. Tuinol Barry, Chelsea, London (1981)

Jo Spence. Stratford Gypsy Site (1974)

Jürgen Schadeberg. May Ball, Cambridge (1983)

Charlie Phillips. Notting Hill Couple (1967)

Chris Steele-Perkins. Girls Dancing in Wolverhampton Club (1978)