Antony Canova, Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss, 1787-1793

At the beginning of each of his photography projects, Bruce Davidson initially views himself as an intruder. He explains that he begins his process as ‘an outsider, usually photographing other outsiders.’ Slowly, as he spends more time in their presence, his subjects relax, Davidson ‘step[s] over the line and become[s] an insider.’ This meaningful transition from outsider to insider allows Davidson to capture the stark realities of differing social attitudes, complex relationships, and intense emotions. Closely attuned to social conditions, Davidson has photographed a plethora of lesser known locations and bustling cities. Throughout his career, Davidson has maintained a critical eye on the social interactions in East Harlem, New York Metro’s underworld, Central Park, and Paris. In one particularly lengthy and fruitful project, Davidson made contact with a gang of homeless, troubled teenagers called The Jokers, whom he photographed over 11 months in New York.

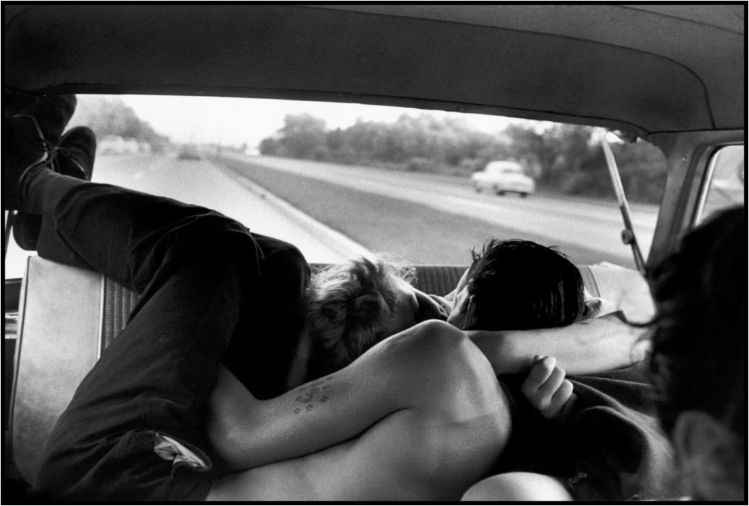

In keeping with Davidson’s immersive technique, Couple Necking in the Backseat depicts two young lovers, both member of the gang, embracing in the back of a car. Their bodies meld together, with arms, shoulders, and hands locked in a tangle of sweat and vitality. When talking about his practice in the early 60s, Davidson explained that he stayed physically close to his subjects in order to ‘be almost in the picture’. Indeed, Davidson has clearly made the transition from outsider to insider within this image, sharing an intimate moment with the car’s inhabitants. The image itself is defined by quick-paced movement, the stretching country road disappearing into the distance as the car gains speed. Within the vehicle, a strong diagonal leads the viewer’s eye across the scene; beginning with two feet at the top left of the composition, running across the couple’s entwined heads, and ending by the snippet of ear shown of the anonymous driver. Using his privileged role as an insider, Davidson invites the viewer to contemplate the scene alongside the two lovers. The photographer’s close-contact with his subjects sheds the element that would usually be understood as voyeuristic, allowing the viewer to take part in a grittier, more authentic side to romance.

A different kiss, far removed from Davidson’s reportage-style photography, was painted by Chagall in 1915. The Birthday depicts the artist and his fiancée Bella, weeks before they were due to marry. Painted with an essence of whimsical frivolity, the couple float into the air as if buoyed by their shared devotion. The interior is vividly coloured and the furniture decorated with a high level of detail. In observing the food on the couple’s table and the view from their window, we understand how the two people live their everyday lives. However, contrary to Davidson’s image, Chagall does not invite viewers of The Birthday to share the adoration he feels for his future wife. Lacking the exclusive outsider/insider dichotomy that Davidson employs, Chagall’s viewer is left only to watch the private displays of affection shared between the couple. Not invited to share the depth of feeling within the scene, the viewer remains a voyeur, contemplating the couple from afar.

Chagall’s overt and gentle depiction of affection follows a wider tradition introduced by the Romanticists during the 19th century. Romanticism consisted of a group of European artists, writers, musicians, and intellectuals creating work characterised by an emphasis on emotion and individualism. Antonio Canova’s Neoclassical sculptural masterpiece Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss is thought to encompass Romantic ideals, possibly acting as a catalyst of the movement’s rapid growth. Canova’s sculpture depicts the mythical lovers embracing in a moment of heightened feeling. The sculpture depicts Cupid awakening the lifeless Psyche with a kiss, as told in Lucius Apuleius’ Latin novel The Golden Ass. The tender moment shared between the lovers is emphasised by Canova’s carving technique which emphasises a creamy, flesh-like softness to the figures. Psyche cranes her arms, reaching up to her lover, who responds by gently cradling her head and breast, ultimately displaying a scene of unparalleled emotion. Canova’s mythical choice of subject and sculptural medium cause an obvious separation between Cupid, Psyche, and the viewer. It is clear that while viewers are invited to look upon the mythical lovers, their devotion remains private and unshared.

Marc Chagall, The Birthday, 1887

It is with both Canova and Chagall’s artworks in mind, that it becomes clear how valuable Davidson’s role as insider truly is. The photographer skilfully creates a direct line of communication within his images, building a relationship between subject and viewer. The scene Davidson presents is not overly romanticised, nor is it entirely emotional. It is as dark and passionate as much as it is loving and affectionate. Indeed, the image presents an immediacy and spontaneity that only Davidson has access to. In Couple Necking in the Backseat, we are rewarded with a moment of passion that resonates with photographer, subject, and viewer alike

(By Eleanor Lerman)