Eileen Cooper, Mirror (1979)

This text was commissioned on the occasion of Eileen Cooper’s 2023 solo exhibition, Ambivalence and Desire. The text is written by Frances Borzello, art historian, feminist art critic and author.

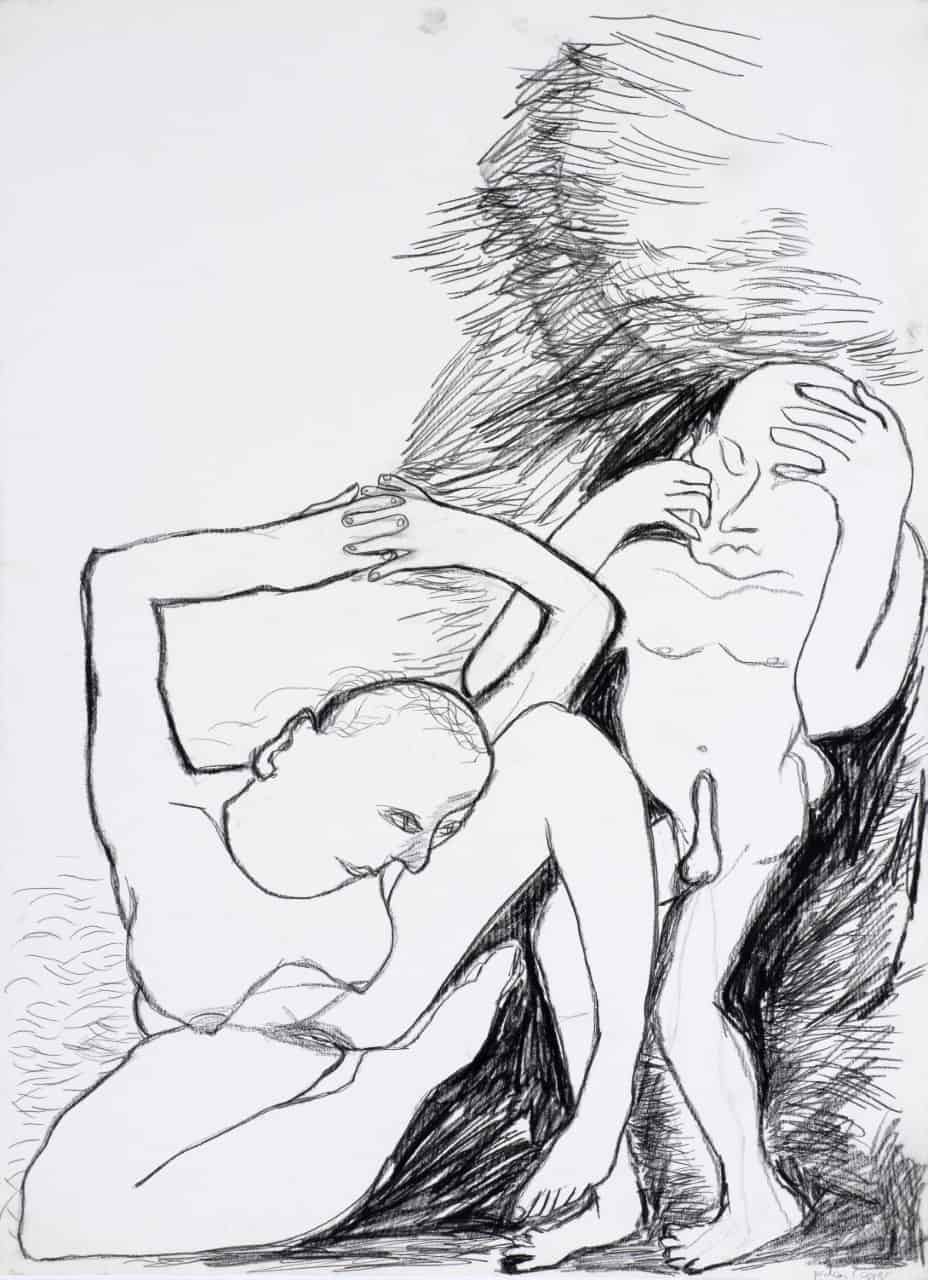

You can always recognise Eileen Cooper’s work. There is something about those women who fill the frame with their jumping, stretching, balancing bodies which could not possibly come from anyone else. Whether the women are dreaming or doing, they seem totally in charge of themselves. There are sometimes men as well, and it is certainly never women versus men in Cooper’s world, but the men never seem to reach that assured quality of her women, never seem quite as interesting. Words like partner or accessory come to mind.

You couldn’t call her a narrative artist because you are never quite sure what the women are up to, perched in the branches of a tree, or stretching their arms to the frame, or standing on one leg on top of a tiger. But though a story might elude you, the mood does not. There is something about her memorable world of women dancing and dreaming, of women communing with animals and trees, which resembles a state of being rather than a mere transcription of activity. It is such a convincing world which technically, I suspect, comes from her strong outline which knows exactly where it is going and from the way her people are positioned within the edges of the frame, so sure of their place that they can touch the edges of their world. That firm outline and the confidence with which her figures inhabit their space suggest that Eileen Cooper knows exactly what she wants to say and exactly how she wants to say it.

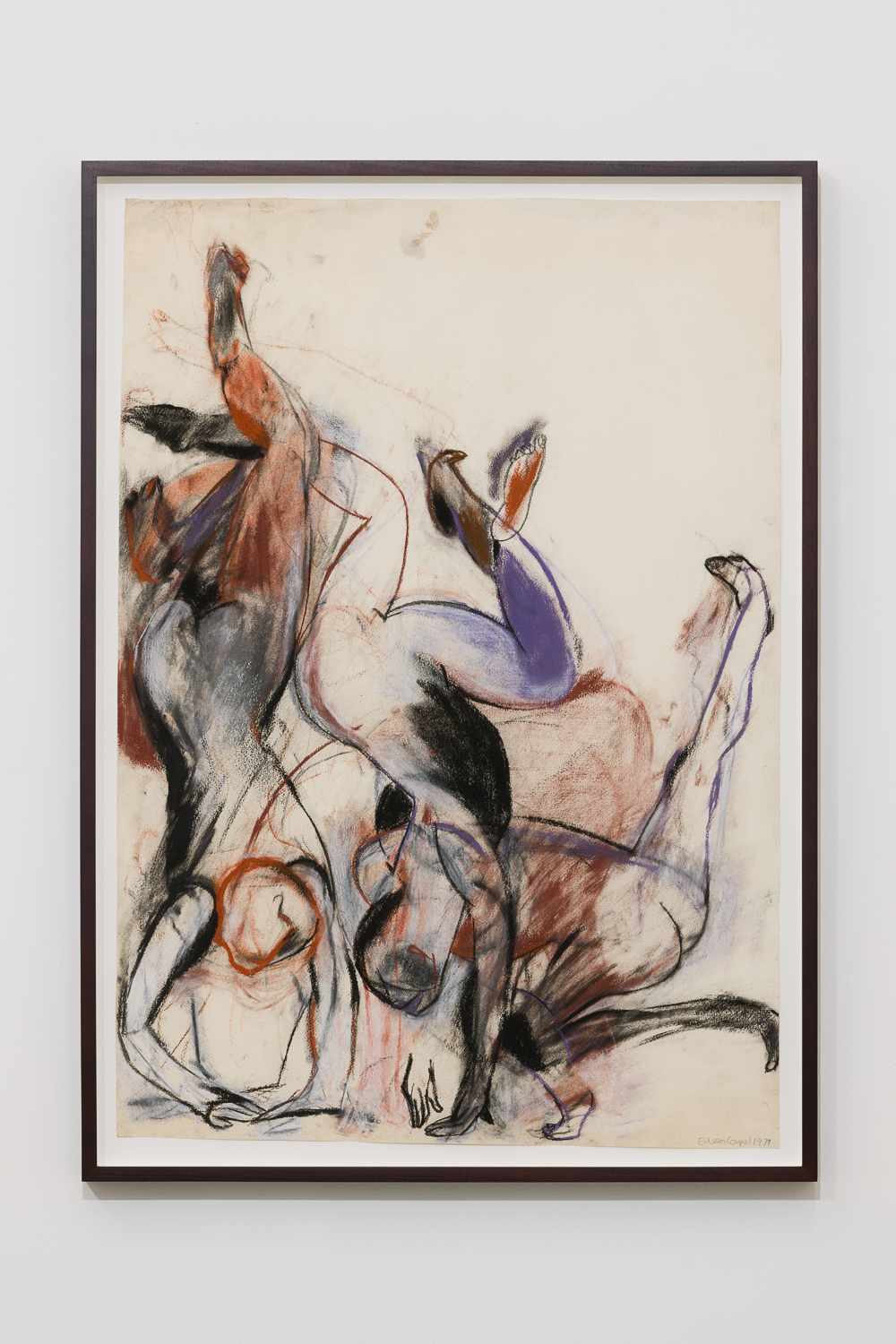

Where did this way of seeing come from? This presentation of a world within the frame that is recognisably ours but with a difference? This intriguing exhibition of early drawings gives us an idea. When she makes them between 1977 and 1983, she has finished with art school – three of them, in fact — and, in time honoured fashion, is supporting herself by teaching while the first of her works are beginning to sell. Every evening she comes back to her small flat, a bit frustrated and a bit inspired by watching her students draw and takes a large sheet of paper and an implement from her boxes of crayons, pencils, charcoal and chalk and makes a mark. Sometimes a nose or the side of a face or maybe just a dot, a line or curve. Which leads to another. And another. These lines do not relate to anything in the room around her. They relate to each other, each one giving directions to the placing of the next one. In her head are bodies, bodies in motion, bodies on swings, bodies on ladders, bodies in mirrors, bodies entwining and bodies responding.

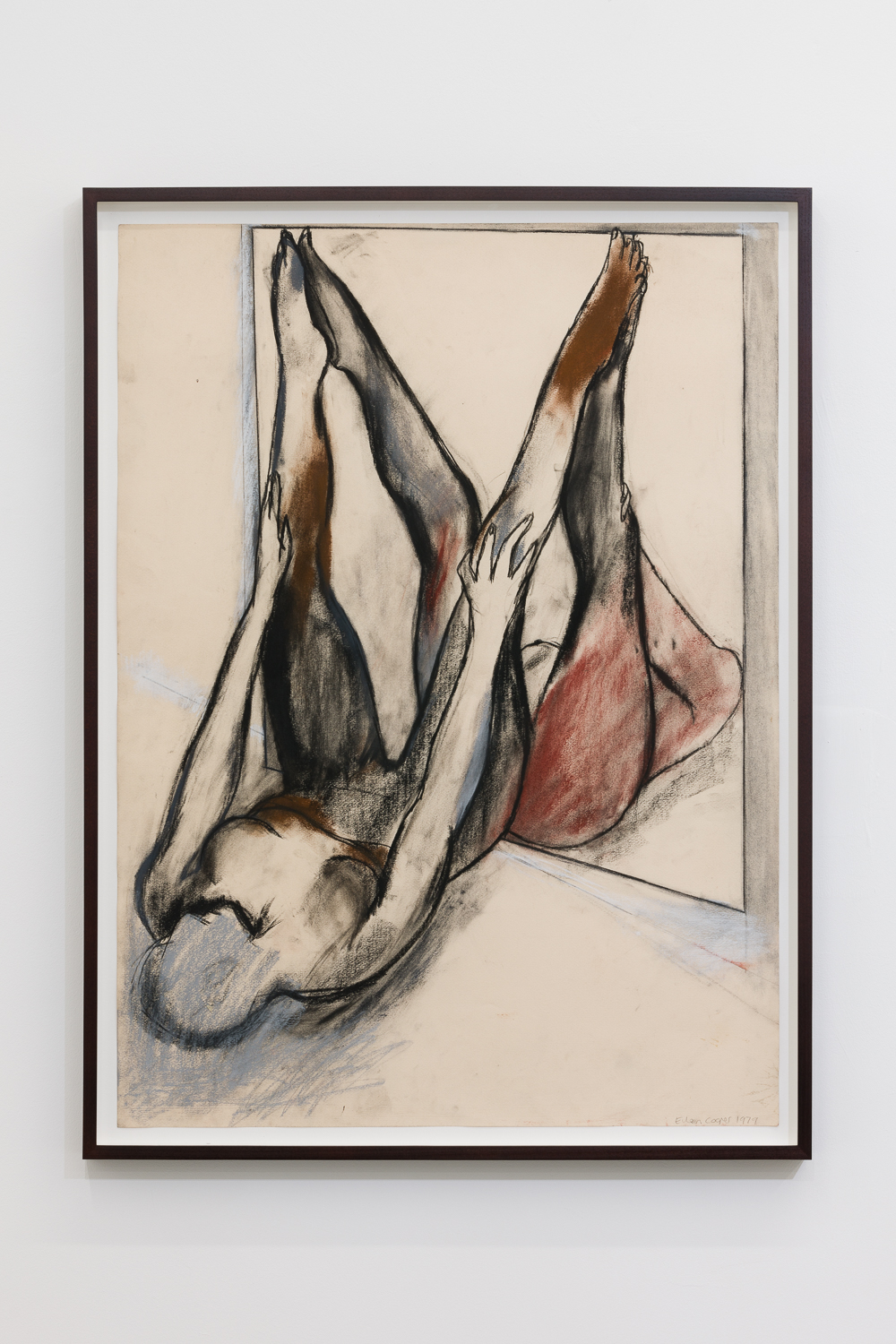

All of the drawings start with people. Plus, sometimes a prop or two to help them along, the mirror, the swing, the seesaw that have stayed the course of her career. A mirror leads to four legs up in the air. A swing leads to two legs in the air, maybe attached to a shadowy body, a web of faint outlines. Sometimes bodies fall from the sky like Blakean angels. Sometimes people crouch, sometimes they race out of the frame. Sometimes these people sprout an extra leg because the drawing demands it. Or an extra head or two.

Sometimes the bodies are sexual because sex has ensnared the artist and she is exploring its pictorial possibilities. The overtly sexual drawings are represented with the curiosity, matter-of-factness and sexual equality of all her drawings. Nobody could call them erotic in that sleazy, behind the curtain sort of way. Speaking as a woman, they are the most relatable representations of love and delight I have ever seen.

But she is not just drawing. She is also testing the limits of her materials. Why use chalk pastels instead of oil? Does charcoal add a special atmosphere to a drawing? Which medium gives a line more confidence? These are drawings of possibilities. Possibilities of where her drawings will take her in terms of her artistic development and possibilities of where life will take her.

Eileen Cooper, Handstand (1977)

In the late 1970s and early 1980s when she made them, feminist art was the most exciting movement of the day, the artistic face of the international female awakening in every single area of life. It was a time when women changed art and the art world in as explosive a manner as Impressionism or Cubism or any of art history’s other ‘isms’, and these drawings are a record of that era. For the first time, women artists felt justified in putting their own concerns into their art which meant the thankless receptiveness of housework or motherhood in all its nappies and boredom instead of the romanticised Madonna aspect presented by men.

In their various ways, the artists were activists as well as artists and as activists, they wanted to explore their attitudes to everything, including relationships between the sexes. One of the issues of the time was women’s realisation that they had no language for talking about their sexual desires and experiences.

Many said they had no idea where to start. Women kept quiet if they had any thoughts at all, but mostly they didn’t have thoughts or none that they knew how to voice. Women’s attitude to sexuality and its right to be in their books, in their art and in their conversation came to a very public head in 1972 when a new American magazine called Playgirl offered its readers a nude male centrefold.

Women artists who wanted to make work about sexuality from a woman’s point of view, understood that men had taken over. The many images of seductive women and many pages of gossip about artists’ models assumed that artists were male. Erotic art was owned by and aimed at men: heterosexual men presented their fantasies of women and gay men their fantasies of men. Women artists had to invent a way to create sexual images that made sense to other women.

In autumn 1980, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London had a season of three exhibitions of women’s art. The first, Women’s Images of Men, was based on the simple idea of asking women to make art about men and caused male critics to sneer in shock and women to attend in their thousands. ‘Whereas, for instance, a male artist is free to show pictures of the female nude and to share intimacies with his audience, a reversal of these roles is not welcomed. When a woman picks up the brush, chisel or camera and focuses her attention on the male, she invites an avalanche of patriarchal opprobrium. Men prefer to cling on to their own versions of reality than to accept the unpalatable fact that a woman’s view may undermine carefully protected masculine myths,’ wrote the organisers. Because its subject matter was based on women’s concerns and experiences, feminist art spoke clearly to its audience, a huge audience, half the population, that did not need to be knowledgeable about art to appreciate the concerns enacted before its eyes. The existence for the first time of an art that was by women for women made even women who were customarily closed to art receptive to its methods and messages.

Women’s Images of Men was a historic exhibition and two of Eileen Cooper’s paintings and one of her drawings, similar to the ones shown here, were chosen for inclusion in it. She describes them as being about sexuality, movement, looking at self and managing relationships, and through them the artist earned her place in art history. In November of this year, a show will open at Tate Britain called Women in Revolt: Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990 to mark this period of artistic activism and Cooper’s 1979 drawing, Figures on Ladder will be included. As this exhibition of her early drawings shows, it is clear that her highly individual way of seeing and presenting life was there from the start of her career

–Frances Borzello, June 2023

(By Frances Borzello)