Although never formally becoming a member of the Surrealist group, André Kertész’s prolonged study of form and keen interest in chance and coincidence mean that his work is often associated with the movement. Kertész is particularly well known for his use of distortion in photography, a trope which he initially became interested in after recognising the refraction of light upon a swimmer’s body in 1917.

It was only in 1933, however, that Kertész began to fully explore the aesthetic possibilities of distortion when the French humour magazine, Le Sourire, commissioned him to complete two series of figural studies. Using a convex mirror from a Parisian amusement park, he stretched and deformed the body of his model: in the process creating a surreal and uncanny mode of portraiture. These portraits were published alongside a text by the writer A.P. Barancy, entitled Fenêtre ouverte sur l’au-dela (window open (on) to the other side), which reads the series as a meditation on what it means to defamiliarise the ordinary by extracting objects from their surroundings. Kertész’s work was therefore seen to explore perception, and the relationship between subject and object.

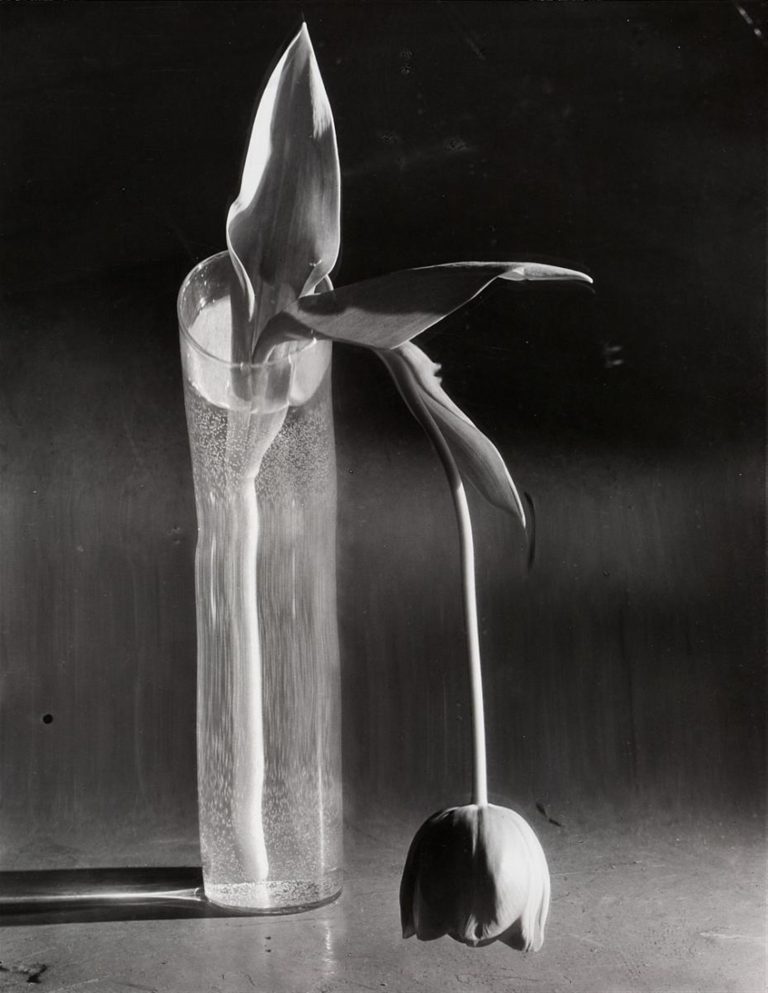

Melancholic Tulip (1939) is one of Kértesz’s best known photographs, and similarly explores the effect of distortion on inanimate objects. The work features a lone, monochromatic tulip in an elongated vase. The viewer’s eye is immediately drawn to the head of the tulip, which hangs bizarrely lower than the surface upon which the vase rests. Central to the image is the struggle to reconcile the strange combination of warped form – the vase – and the photorealism of the tulip’s head and vase’s shadow. Kertész’s use of a plain, textured background and strong lighting abstracts the flower from the field of the ordinary, and allows this piece to resonate with the surreal landscapes of Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico.

Many have read this picture autobiographically, seeing the wilted tulip as a comment on Kertész’s time in New York at the outset of the Second World War. Missing Paris and becoming disillusioned with his lack of success in a strange new city, the tulip can be understood as emblematic of disappointment and sadness. This reading is supported by Kertész’s choice of title, which anthropomorphises the plant: its drooping head becomes an almost comic, exaggerated metaphor for solitude and neglect