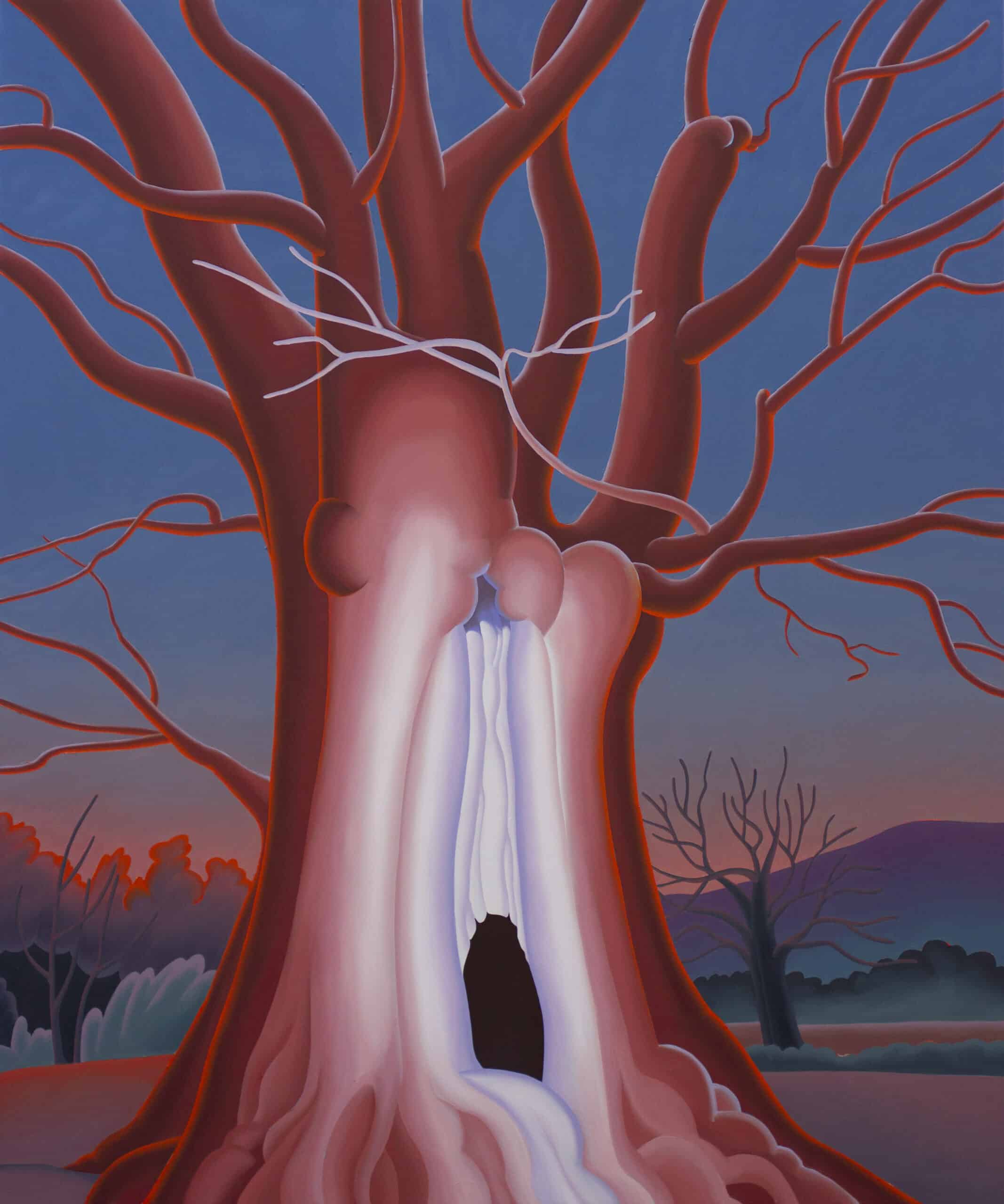

Madeleine Bialke, Deadheart, 2023 (detail)

“It was a comrade, bending over the house, strength and adventure in its roots, but in its utmost fingers tenderness, and the girth, that a dozen men could not have spanned, became in the end evanescent, till pale bud clusters seemed to float in the air.”

This description of the wych-elm that occupies the centre of the titular house’s garden in E. M. Forster’s Howard’s End affirms the anthropomorphic quality of the tree. It is at once a familiar presence – strong, friendly, tender – but remains incomprehensible in its totality. Caught between the monumental and transitory, Forster’s elm retains a fundamentally mystical quality.

The Welsh Oak in Madeleine Bialke’s Deadheart is characterised by a similar duality of the knowable and unknowable. Rendered in an almost fleshy red-pink gradient, Bialke’s oak is personified, occupying the position of the sitter within the portrait-like composition of the painting. Gnarled bark ripples across the trunk to suggest bulbous abdominal muscles and spindly branches rise like outstretched arms from the tree’s torso. Yet the tree’s gigantic stature is amplified; we gaze up at its monumental body – otherworldly in scale – from a firmly human point of view. The oak appears on the boundary of two worlds, acting as a portal between the natural and supernatural.

Deadheart comes from Bialke’s series ‘Giants in the Dusk’. Each of the grizzled and swollen arboreal bodies depicted by Bialke are ‘giants’ in their monumental stature, but also in the mythical sense too: centuries old, the trees exist outside of our own temporal reality. Giants in ancient mythology, as described by Hesiod, were children of Gaia, born of the blood that fell as Ouranos was castrated by Cronus. Much like trees, the Giants grew from the bloodstained earth as small seedlings and soaked up the sun, growing slowly as the seasons turned.

Deadheart’s Welsh Oak echoes this sanguinary history: glowing bright red at its edges, the body of the tree appears to pulsate as if sustained by a circulating blood flow. But the oak’s vitality is threatened; the tree’s core is hollow, a cavernous black space left by its rotten core. The tree, it seems, is reaching the end of its three-hundred year lifespan, about to enter an afterlife as a skeletal, spectral presence in the landscape

(By Flora Clark)