Cooper’s art, with its unwieldly proportions and distorted perspective, has always been tied to the past, particularly early non-Western and medieval works. Here that tie feels especially strong given the mythical subject matter and the antiquity of the land. And yet, there’s something entirely contemporary – and entirely relatable – about these paintings and what they say when it comes to ageing and remembrance and the quest for self-knowledge. They’re about making sense of the world and our place within it, the power of the land and the way that power is passed on.

Chloë Ashby

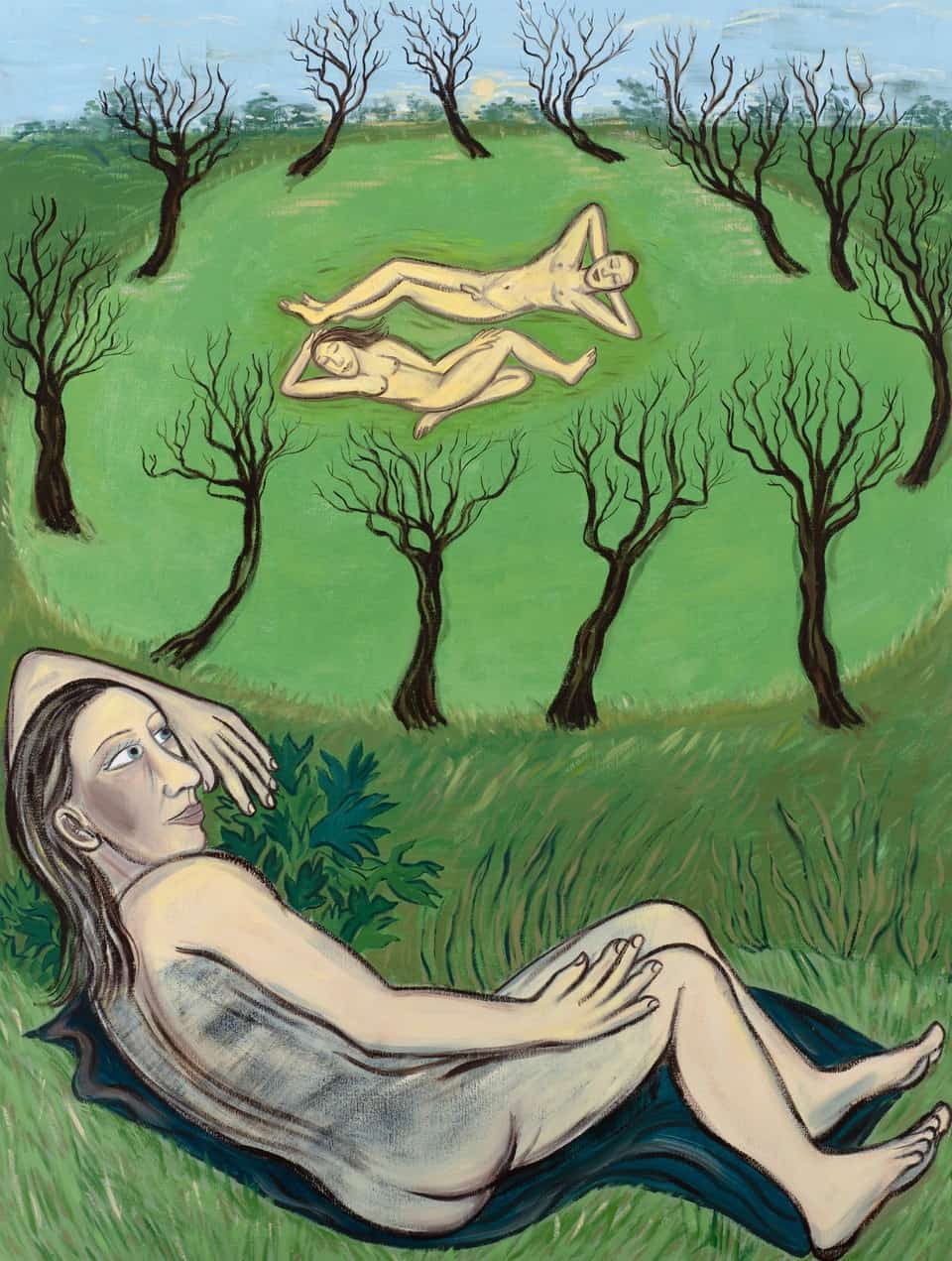

Eileen Cooper, The Lily Pond

This text was commissioned on the occasion of Eileen Cooper’s 2022 solo exhibition, Somewhere or Other. Written by Chloë Ashby, novelist and critic.

A woman with wide eyes and long, slender fingers lies naked in a field. She’s on her side, legs bent at the knee, head propped up in the crook of her arm, a makeshift pillow. From where she is, she’s got a good view of a young couple, also naked, their creamy bodies laid out like washing to dry in a sunny clearing bordered by a ring of winter trees that have shed their leaves. She could be a voyeur. Or she could be a woman of a certain age looking back on her life, at her younger self.

A sense of nostalgia rattles through the wild and free paintings that Eileen Cooper made after spending three months in Suffolk last autumn. A sense of history and of change. A sense of reflection. Back in her studio in south London, on a warm day in mid-May, she describes to me the way she would head out each morning before breakfast, whatever the weather, and walk across flat fields beneath large skies, the horizon hanging low and heavy. She would return to the house tired and blown about by the wind, but not too tired to sketch. She had taken with her a pen and ink, watercolours, plenty of paper.

Cooper tells me over a mug of milky tea that she never wanted to be a landscape artist. How can you be working outside when everything changes all the time, she marvels. The light puzzled her. She was afraid of the colour green. In Suffolk, something changed, and she found herself engaging with nature in new and unexpected ways. When we last spoke, a couple of years ago, she said that for her everything starts with a figure – or a hand, an eye, a nose. With these paintings, the land went and she followed.

Each canvas began with a glade, a lily pond, a weeping willow tree – a natural framework into which she would squeeze one figure or more. She wanted the people to have as much presence as the nature, and her solution to keeping them big was to lie them down or flip them on their side or cram them into a tree. The landscape is experienced either from low down or up above. This is work about being in and at one with nature. It’s about the sensation of dewy grass on dry skin. The sound of a moorhen bobbing about on a lake, dipping its beak beneath the surface. Hair caught on rough bark or a crooked branch.

Eileen Cooper, Winter Sun

Borrowing Light shows a woman crouching in an old oak tree, her jaunty limbs coiled around its meandering trunk, her blue-black tresses wind-whipped and wavy. There’s an unruliness to these paintings, with their jostling bulrushes and ripples of water, even the weathered faces of the figures. Also, something childlike – after all, when’s the last time you climbed a tree? The sense of play shines brightest in Follow the Blue Sky, with one woman balancing barefoot on a branch, another perched on a swing.

Every time I use a swing, Cooper tells me, it goes back to that memory of childhood, when you’re on your own and there’s nobody pushing you and you’re testing how high you can go. You’re suspended mid-air and the swing is moving, you’re enjoying yourself, but you’re also terrified of going up and over the top. I’d be terrified too, I tell her, if my swing were attached to a branch as spindly as the one in her painting. We may be in nature, but there’s magic here, too. Logically, there’s no way Cooper’s trees could hold her intrepid women, and yet, they’re hanging out in them quite happily.

Cooper found freedom in painting not just the world we inhabit, but a world of memory and imagination and possibilities. Also, a world of folklore and myth. The Suffolk coast and countryside are rich with history and tales of ancient habitats and communities that have either vanished or been swallowed by the sea. It’s hard to look at Borrowing Light and not think of Daphne turning into a laurel tree to get away from Apollo, or to see in The Wild Place a nod to Narcissus, doomed after falling in love with his own reflection.

Cooper’s art, with its unwieldly proportions and distorted perspective, has always been tied to the past, particularly early non-Western and medieval works. Here that tie feels especially strong given the mythical subject matter and the antiquity of the land. And yet, there’s something entirely contemporary – and entirely relatable – about these paintings and what they say when it comes to ageing and remembrance and the quest for self-knowledge. They’re about making sense of the world and our place within it, the power of the land and the way that power is passed on.

Things come full circle in Barefoot Runaways, the final painting in the series; Cooper refers to it as the odd one out. She had been working over Christmas and into the new year, and by then she was sick of the cold and the dark and craving a change of palette. Soft blue-greens gave way to glowing lilacs and blushing oranges. There’s a hint of a landscape, hills rising like waves in the distance, but really this is their story. The wide-awake man with the blue trousers and the bare chest. The dreaming woman with the flame-like top and skirt. They could be lying on a picnic rug in a field in Suffolk, watching the sunrise, or the golden-yellow cloth could be a flying carpet.

Before we say goodbye, I ask Cooper how she came up with the exhibition’s title. She tells me she borrowed it from Christina Rossetti; there was a book about her in the house in Suffolk, and Cooper spent some evenings reading about her and reading her poems. She liked that the title was both general and strangely focused – somewhere or other – and that’s what I like about these paintings, too. The way they’re rooted in the earth and at the same time gently floating above it. The way they give the land and the viewer room to breathe. The way they look back to look to tomorrow.

(By Chloë Ashby )