It is as if something that seemed inalienable to us, the securest among our possessions, were taken from us: the ability to exchange experiences.

Walter Benjamin Illuminations (Schocken, 1999)

I.

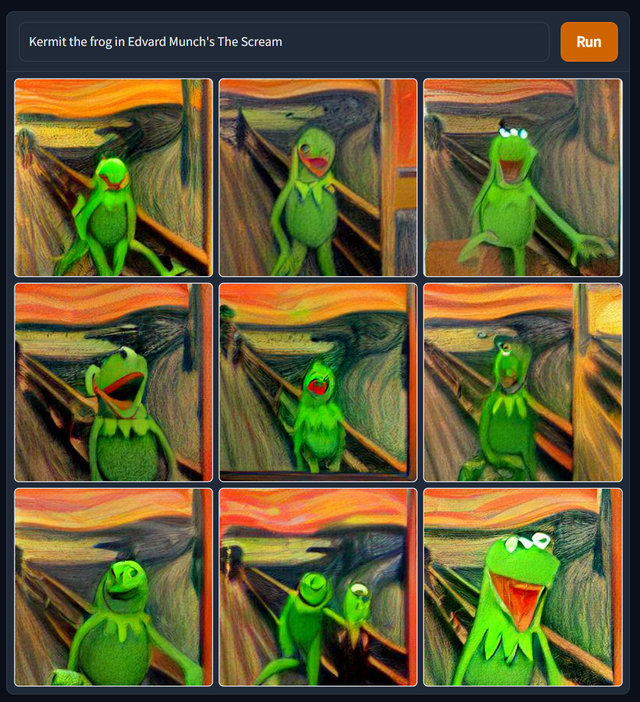

I’m looking at a picture on the internet – one picture divided into a grid of nine, smaller pictures, to be exact. Within each carefully delineated square is a different version of the same scene: a beautiful painting depicted in rich umbers, deep, mottled blues, and terracotta reds surging viscously across the picture plane. In the distance a lake sprawls languidly, girdled by regal mountains; in the sky a sun sets, lazily. At the centre, an emerald figure stands upon a bridge. He is tormented, prophetic, austere. In some pictures, his eyes stare, obliquely, into the middle distance; his limbs hang, undelineated; his wet, red mouth is gorged open wide in a gesture of universal ennui. He is green and has a spikey felt collar, and – oh, it’s Kermit the Frog.

It’s nine pictures of Kermit the frog, depicted in the style of Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893), courtesy of DALL·E 2: a publicly available and of late widely utilised AI image generating software, which allows users to generate realistic images of anything they like. The user’s choice here is comic, as Munch’s The Scream is widely touted as a universal portrait of modern spiritual anguish. Funnily enough, Munch’s prevalent themes: mysticism, chronic illness, psychology, religious aspiration – remain unchanged, if added to, in this contemporary iteration. The painting still screams.

Aside from fantastic memes, the rise of DALL· E 2 marks a moment of unprecedented machine learning, granting the public with a god-like ability to merge, generate, and summon images at will. At the same time, it seems to speak to a contemporary zeitgeist – one in which heterogeneity reigns, and the value of personal experience wanes. Here, feeds are lined with jarringly unrelated content: the war in Ukraine to lifehacks videos, celebrity gossip to climate disaster, nuclear armament to horoscopes. This comes, necessarily, with a prevalent sense of disenchantment, ennui, doom scrolling, and powerlessness. It is within this long-horizoned landscape that our exhibition operates. Munch’s Kermit the Frog does well to illustrate this modern, spiritual bankruptcy.

Open, 2022, and Close, 2022. Charlotte Edey

II.

What’s in a myth? There is a particular security that comes from texts that are old and sacred, whether they be classical, religious, or literary. Natalia González Martín’s work transplants the legs of Adam and Eve on Jan Van Eyck’s fourteenth century Ghent altarpiece onto a de Chrico-esque, infinite horizon. The diptych’s limbs – soft, curvaceous, glistening – are set into profane, narrative motion by the introduction of one glistening bead of moisture on Eve’s upper thighs. Jakob Rowlinson queers the archive with his BDSM iterations of english, pagan, folklore. Mask II, 2021, depicts the green man – a foreboding symbol of reckoning with oncoming spring – replete with chains, heavy piercings, and decorative, leather perforations. Dangling from the ceiling with a permanently open mouth, Rowlinson’s juxtapositions here capitalise on the often forgotten sexual spirit of Early English and Germanic oral storytelling.

Jeanine Brito’s Something Borrowed, 2022, subverts the idea of the fairytale wedding. Here, a woman pouts floridly in marriage attire. Her almost theatrical gesture of sadness capitalises on the narrative potency of an unhappy bride – a jilt at the altar? An unwelcome marriage? Tristan Pigott’s Margaret of Antioch, 2019 references in hyperrealistic splendour the medeival Turkish Saint Margaret, who, having been eaten whole by the devil disguised as a dragon, escaped unscathed, with the aid of a crucifix. Strangely, despite adding to a millenia of artists who have chronicled Saint Margaret’s triumph over evil, the work touches on the modern experience through form: the painting is hyperreal like a cartoon, smooth like a phone screen, and curled like an ageing poster at a train station.

Other works indulge in the future: Molly Greene’s abstract paintings turn on the idea of scientific bodies, nomenclature, and life on a microbial scale to create works that straddle sentience and insentience. Dispersal, 2022, details a biomorphic shape with curious tentacles, probing a smooth, cool, gradient background. Here, Greene reimagines organisms as aliens with curious agency.

In a climate of external heterogeneity, the solid knowability of the body can also offer speculative, spiritual salve. Interiority and extremities are explored in depth by Alicia Reyes McNamara, whose paintings probe bodies, gender, sex, and specifically Latinx identity through alien, twisting figures. Relying on the imaginative potential of orifices and outlines, McNamara’s pieces explore self and other in deep blues. At the heart of Salomé Wu’s lustrous, blooming, Touched the Land with It’s Healing Hand, So Fleeting, 2022, is Wu’s own self mythology – an extremely personal text she has been writing for several years, chronicling her own interior monologue. The colours of the piece – fleshy pinks and purples – physically indicate this radical interiority. Charlotte Edey’s works – Open, Close, 2022 – use bodily forms to consider the ancient and alluring fear of seduction. The pieces are inspired by the Venus flytrap, and in particular its namesake, Aphrodite. The open and closed jaws which circle Edey’s central drawings lend the works a primal paranoia regarding consumption, and the destructive power of sensual femininity. Calling to mind Aphrodite’s trials under Hephaestus, Edey’s plush cushions and hand-held mirrors weaponise instruments of femininity.

Much as the surrealists used the power of dreams to counter a modernist, mortal anxiety, the works of Mary Herbert and Grace Mattingly harness the power of fantasy in their mythical canvases. Mattingly’s Girl and Lion, 2022, sees two characters wordlessly interfacing in a bucolic scene. The palette of the piece – orange, yellow, pink – lends it a surreal otherworldliness. There is also enchantment in the work’s details: sumptuous, rolling, body-like hills in the distance; flashing claws in the foreground. As with Aesop’s fables, there is a thick, narrative tension in the scene. Both Mary Herbert’s One Door Closing, 2021, and Shore, 2022, capitalise on a diaristic sense of dreams half remembered, floating, faceless characters, and liminal boundaries – entryways, oceans, ghosts, to suggest a hazy, fictional idea of elsewhere.

Perhaps Grace Lee is the only artist in the exhibition who dares mythologise the contemporary. Taking from current image economies (or what she terms ‘orphaned’ images) – infographics, shutterstock pictures, google image archives, tarot cards – to create quiet, darkly comic, and sometimes bizarre painting. The Opener, 2021, explores ideas of performance, production, exploitation. In cirque-du-soleil fashion, a fish theatrically expels the very water it needs to survive. The reference to Kim Kardashian’s 2014 Paper Magazine cover is coincidental, but not meaningless.

The Opener, 2022. Grace Lee

III.

In his 1936 essay, The Storyteller, Walter Benjamin laments a mid-century death of storytelling. In a winding treatise, he collects his thoughts on this subject – the withering of the classical epic into the short story, how men returning from war were not richer, but ‘poorer in communicable experience’, and the waning presence of eternal thinking and death in everyday life. Chiefly, however, he attributes the demise of the storyteller to the fact that experience itself has ‘fallen in value’. At every glance of a newspaper, he sees the value of fairytale as being contradicted by ‘strategic experience’, ‘tactical warfare’, and ‘economic experience by inflation’ – imagine Benjamin on Google!

New Mythologies II restores a richness to a climate that places increasing weight on logical thinking, a contemporary image economy, and an exponentially extended metaverse. Through play, fantasy, and dreams, New Mythologies II calls on the enduring fascination with fairytale to restore potency to myth, and spirituality to storytelling.

Kermit the Scream. Courtesy of DALL·E 2

(By Lydia Earthy)