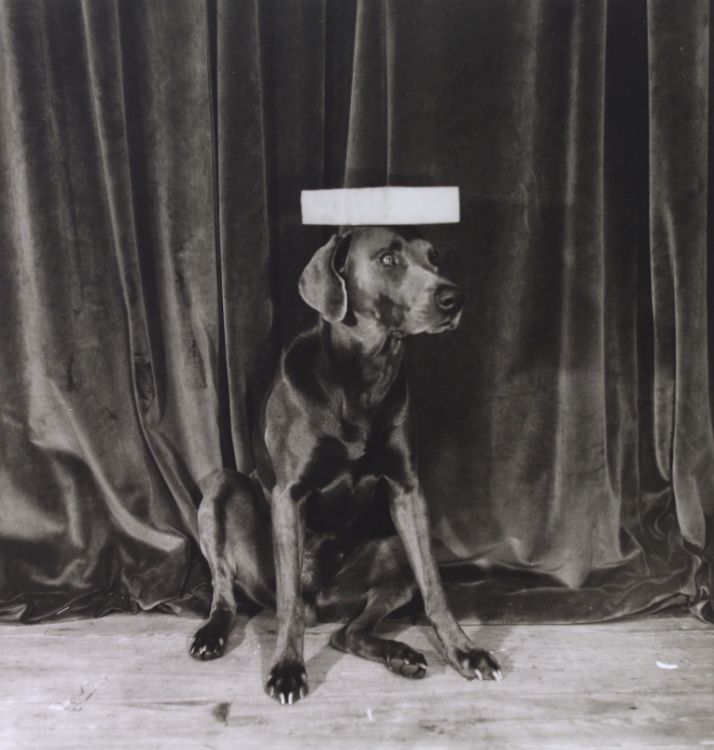

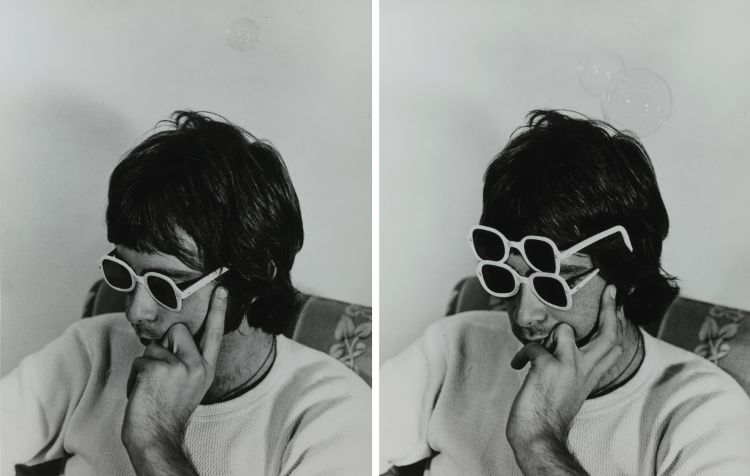

Funglasses, 1970

William Wegman bought his first Weimaraner when, aged 26, he relocated from Wisconsin to Southern California, where he had taken up a teaching post at California Stage College, Long Beach. He named the dog Man Ray, after the famous Surrealist. At this time, Wegman’s conceptual-based art practice was performance orientated. He embraced video and photography particularly for their non-artistic, lo-fi potential, and his work used the two mediums to comment on contemporary culture and society. Wegman’s pioneering video pieces were particularly concerned with humour and self-awareness – often lampooning the pretentions of the same conceptual art that he himself was making. Man Ray began appearing in these video works almost immediately and the dog and the artist developed a deeply collaborative creative relationship. Man Ray enjoyed performing for the camera, and, as Wegman has since said, Man Ray ‘looked great, a lot better than the bits of cheese or nails I was conceptually placing in the corner, and he was grey, that seemed to suit black and white video very well.’ Man Ray’s endearing presence, always interested but usually perplexed, in Wegman’s works proved to be the essential foil to the more academic and sober conceptualism that Wegman was satirising.

The 1971 video piece Milk/Floor sees Man Ray interrupt a seemingly conceptual, intricate performance piece being carried out by Wegman. The artist, on all fours, backs slowly away from the camera, and dribbles milk pointedly and deliberately in a line across the floor of his studio. Before the viewer can attempt to decipher the mark making and its meaning, Man Ray promptly enters the scene and enthusiastically laps up the artworks remnants, bumping into the video camera with his snout in the process, abruptly ending the piece. In the 1973 video work, Spelling Lesson, Wegman begins to explore anthropomorphism, a theme that would go on to play a large role in his Polaroid work, and revels in the implicit surreality that ensues. Wegman and Man Ray sit on chairs at a table as the artist patiently explains to the attentive but uncomprehending Man Ray that a word has been misspelled in the dog’s spelling test. The artist is completely deadpan in his constructive criticisms directed at the dog, as he agonises over the particular intricacies of the phoneme. The dog cocks his head, and whines in response.

These two early experiments with film demonstrate how Man Ray’s inclusion in Wegman’s work positioned the dog in the role of the viewer, trying to navigate his way through the rigours of conceptual art practice. This was vital in the resulting lucidity and humour of the works, and in establishing a communication directly with the audience. It was the dog’s innocence, and his serene obliviousness, that became such a useful vehicle for parody and play in subsequent works

(By Thea Gregory)